This is part seven of a multi-part series reviewing Canada’s Anti-Spam Legislation in practice since its introduction in 2014 and the beginnings of enforcement in 2015. Crosslinks will be added as new parts go up.

Part 1: Terminology

Part 4: Case File – Compu-Finder

Part 5: Case File Anthology, 2015-2016

Part 6: Case File – Blackstone Education

Part 7: Case File Anthology, 2017-2018

Part 8: Case File – Brian Conley/nCrowd

Part 9: Case File Anthology, 2019-2022

Core resources:

Enforcement Actions Table (CASL selected)

March 9, 2017

March of 2017 comes in like a lion, with a $15,000 decision against William Rapanos, the creator of flyers for distribution via Canada Post.

The decision is rare in that it articulates the complaints the CRTC received, and recreates a message in the decision:

Compliance and Enforcement Decision CRTC 2017-65, s11

In the present case, 50 individuals filed a total of 58 submissions with the Spam Reporting Centre regarding the messages at issue.

These submissions included the messages that advertised flyer design, printing, and delivery through Canada Post. For example, the content of one of the submitted messages consisted of the following:

Subject: Canada Post flyer delivery – Art Design and Printing included starting at only $599 for 25,000 homes!

Do you need to send out flyers? Like any direct marketing flyers work by repetition. Statistics say that the average person must see an ad at least 3 times before they react to it. In fact this is why many companies that send out a flyer once and then give up will fail with their direct marketing efforts. For this reason we are offering the following package:

– You choose an area that’s local to your business

– We will select 25,000 homes in those postal codes

– We will professionally design an ad for your business

– We will print your ad on a full colour glossy 8X5 double sided flyer

– We will deliver it with Canada Post 3 times over the next 3 months TO THE SAME AREA

Total cost: $599 per month for 3 months

Result: Your phone will ring all summer long!

Get more information by visiting this page:

http://postalflyers.club/

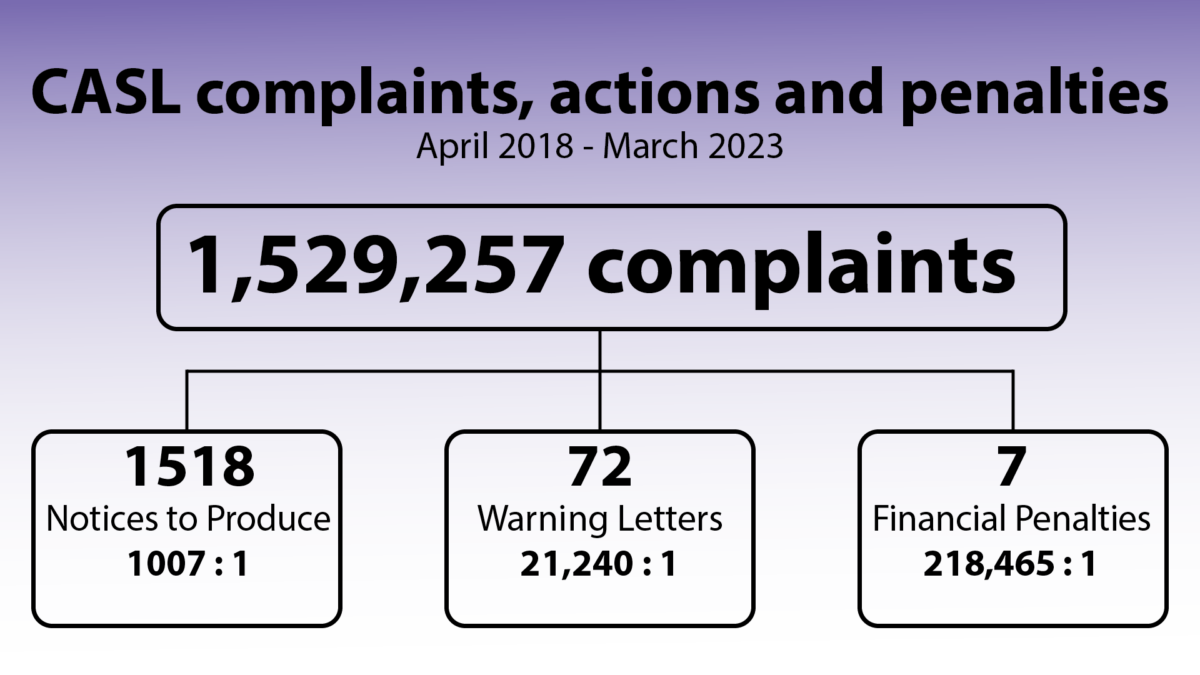

It’s hard to parse where the CRTC / CASL takes action on these. 50 individuals and 58 submissions doesn’t seem like much, ranked against the 218,000:1 ratio that leads to financial penalties. Without understanding the day-to-day workings of CASL – chiefly, how submissions cluster (maybe 58 is a very high number for a single organization?), it’s difficult to say whether 58 submissions is an eyebrow-raising amount. If not, it’s hard to know why Rapanos was selected.

But – as far as violations go, Rapanos batted the circuit: his messages sent without consent, without contact info or an unsubscribe mechanism.

I love this case, because it has an an awe-inspiring legal Hail Mary by Rapanos, who claimed somebody pirated his Wi-Fi and sent the messages without him knowing, and that he had no connection to a business he very clearly owned [s26-29]: “The suggestions that Mr. Rapanos was potentially the victim of identity theft or that someone unknown to him accessed his unsecured home Internet connection are not persuasive, since they were not supported by any other indicators of fraud or of evidence that his identity had otherwise been used for malicious purposes. Neither Mr. Rapanos, nor any of the other individuals who were asked to do so through notices to produce, provided to the investigator any documentation to support the claim that boarders had resided in Mr. Rapanos’ house or accessed his Internet connection.”

There is never a bad time to drop a reference to what I think is one of the greatest comedy sketches of all time, and I thank Mr. Rapanos for this opportunity:

[s27-29] rebuts this at length, and essentially boils down to “oh, come on.”

As seems common, postalflyers.club is no longer in operation – the domain has no current owner and is available for registration per a WhoIs search. The Wayback Machine has never archived the page, possibly because it’s a redirect to another site that doesn’t exist any more, per [s14], http://firstunitedpartners.com, which also is defunct, available on a WhoIs search, and per the Wayback Machine was only a “domain for sale” notice as of October 2015.1Side note: It’s curious that William Rapanos is a “Toronto-area” man at the time of filing, and there’s a 2014 investigation against a Sharon Rapanos of Bowmanville, in the GTA. I can’t find an evident connection between the two, but it’s not a common last name. The NTP for Sharon Rapanos was a demand to produce the names of anyone who had access to her Internet from July 2014 to June 2015, and given William’s reliance on “I was hacked” as his defense above, there seem to be some dots that can be connected. Or not. The universe is big and full of coincidences.

Issued penalty: $15,000

Final penalty: $15,000

Total issued AMPs: $2,207,000

Total imposed AMPs/monetary penalties: $813,000

Differential: $1,378,000

June 12, 2017

$10,000 monetary compensation paid by Ghassan Halazon “in his individual capacity”.

Short and sweet: it looks like he was the CEO of several deals sites, now bankrupted, but still responsible for CEMs sent by Couch Commerce, and “agreed to make a monetary payment of $10,000 to the Receiver General of Canada”.

Undertaking: Mr. Halazon and TCC

File No.: 9090-2015-00414

Date of the undertaking (signed by all parties): 12 June 2017

Monetary payment: $10,000

Pursuant to section 21 of the Act to promote the efficiency and adaptability of the Canadian economy by regulating certain activities that discourage reliance on electronic means of carrying out commercial activities, and to amend the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission Act, the Competition Act, the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act and the Telecommunications Act, S.C. 2010, c. 23 (the Act).

Persons who entered into an undertaking

Mr. Halazon, in his individual capacity, as former Chief Executive Officer of Couch Commerce, Inc. and its subsidiaries 8108773 Canada Inc. and DealFind.com Inc., operating as Teambuy and Dealfind (“Couch Commerce”), since bankrupted ; and

Transformational Capital Corp. and its subsidiaries, Evandale Caviar Inc. and Mighty Deals Limited, operating as Buytopia.ca, Shop.ca, Shop.us and Mightydeals.co.uk (“TCC”), also represented by Mr. Halazon as CEO.

Acts and omissions covered by the undertaking and provisions at issue

Mr. Halazon has voluntarily entered into an undertaking with a designated person of the Commission in relation to an alleged violation of paragraph 6(2)(c) and non-compliance with subsections 11(1) and 11(3) of the Act, as well as subsection 3(2) of the Electronic Commerce Protection Regulations (CRTC).

The investigation alleged that commercial electronic messages (CEMs) were sent or caused or permitted to be sent by Couch Commerce to recipients without a compliant unsubscribe mechanism during the period of 2 July 2014 to 9 September 2014, while Mr. Halazon was CEO of Couch Commerce. More specifically, it was alleged that the unsubscribe mechanism did not function, or could not be readily performed, or unsubscribe requests were not given effect until more than 10 business days after a request has been sent. It was also alleged that Mr. Halazon was personally liable for this violation pursuant to section 31 of the Act.

Amount payable and summary of other requirements

As part of the undertaking, Mr. Halazon has agreed to make a monetary payment of $10,000 to the Receiver General for Canada in accordance with subsection 28(3) of the Act.

In addition to this payment, TCC, a company which acquired the email list initially used by Couch Commerce and which is also represented by Mr. Halazon, agreed on a compliance program. This program includes elements such as a review of current practices, development and implementation of corporate compliance policies and procedures, training for employees, consistent disciplinary procedures, tracking of CEM complaints and subsequent resolution, monitoring and auditing. This program also includes reporting mechanisms to Commission staff with respect to its implementation, as well as other requirements, such as reporting significant changes affecting the business and full cooperation in case of visits or requests from Commission staff.

This undertaking fully resolves all alleged or potential liability for all CEMs sent by and on behalf of Mr. Halazon and TCC from 2 July 2014 up to the date of the undertaking.

If Couch Commerce Inc. was a company, why was Mr. Halazon pursued as an individual / the CEO under the Act? Other actions have been taken against companies — both previous, such as Kellogg and Blackstone, and even just below, with 514-BILLETS. Vicarious liability, which is not detailed in this action, but will come up soon when we look at Brian Conley and nCrowd.

Issued penalty: $10,000

Final penalty: $10,000

Total issued AMPs: $2,217,000

Total imposed AMPs/monetary penalties: $823,000

Differential: $1,378,000

Kiss of Death: Dead as Doornail 2I get curious about things, so looked up “Ghazan Halazon” on LinkedIn, and found two profiles — the first, “dealfindingghazanhalazon” is the CEO of Couch Commerce, still lists Ghazan Halazon as its CEO, but there’s a second Ghazan Halazon, with an identical education background, but who mysteriously doesn’t mention Couch Commerce at all. Does this count as two?

March 15, 2018

Monetary compensation of $100,000 from 9118-9076 QUÉBEC INC. and 9310-6359 QUÉBEC INC. (514-BILLETS) (https://crtc.gc.ca/eng/archive/2018/ut180315.htm)

First of all, that’s a pretty sweet phone number. 514 is the area code for Quebec, and BILLETS is a 7-digit combination that’s French for “Tickets”.

Second, while previously there didn’t seem to be a distinction between “monetary compensation” (paid to the Receiver General) and AMPs (generally “paid in accordance with the instructions contained in the notice of violation”) in the past, there’s a big swing here. As often, this is brief enough that we can put it in an accordion, but I’ll ask you to pay attention to the bit at the bottom, about payment:

Undertaking: 9118-9076 QUÉBEC INC. and 9310-6359 QUÉBEC INC. (514-BILLETS)

File No.: 9090-2015-00415

Date of the undertaking (signed by all the parties): 15 March 2018

Monetary compensation: $100,000

Pursuant to section 21 of the Act to promote the efficiency and adaptability of the Canadian economy by regulating certain activities that discourage reliance on electronic means of carrying out commercial activities, and to amend the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission Act, the Competition Act, the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act and the Telecommunications Act, S.C. 2010, c. 23 (the Act)

Persons who entered into an undertaking

9118-9076 QUÉBEC INC. and

9310-6359 QUÉBEC INC.

Acts and omissions covered by the undertaking and provisions at issue

9118-9076 QUÉBEC INC. and 9310-6359 QUÉBEC INC. have voluntarily entered into an undertaking with the Chief Compliance and Enforcement Officer concerning alleged violations of paragraphs 6(1)(a), 6(2)(a) and 6(2)(b) and non-compliance with subsection 10(1) of the Act, as well as non-compliance with section 4 of the Electronic Commerce Protection Regulations (CRTC) (CRTC Regulations).

9118-9076 QUÉBEC INC. and 9310-6359 QUÉBEC INC. both operate under the name 514-BILLETS to carry on commercial activities related to a ticket resale service for cultural and sports events in Canada, specifically in the Montreal, Quebec City, Ottawa and Toronto areas.

Both corporations are responsible for sending commercial electronic messages (CEMs), mainly in the form of text messages (or SMS, for “Short Message Service”), promoting their commercial activities.

Between 3 July 2014 and 26 November 2015, the Spam Reporting Centre (SRC) received submissions related to these CEMs and CRTC staff launched an investigation with regards to these submissions. The investigation alleged that 9118-9076 QUÉBEC INC. and 9310-6359 QUÉBEC INC. sent or caused or permitted to be sent CEMs between 1 July 2014 and 20 January 2016, without the recipients’ consent and without setting out the prescribed information enabling the recipients to easily identify and contact the sender.

More specifically, the majority of CEMs sent by 9118-9076 QUÉBEC INC. and 9310-6359 QUÉBEC INC. were requests for consent, offering the recipients the opportunity to receive future commercial offers. These messages presented the following format: “ Would you like offers for discount tickets for [...] ” while sometimes including a short list of proposed event categories.

According to section 4 of the CRTC Regulations, a request for consent must include a number of pieces of information, including the name, mailing address, and either a telephone number providing access to an agent or a voice messaging system, an email address or a web address of the person seeking consent or, if different, the person on whose behalf consent is sought, as well as a statement indicating that the person whose consent is sought can withdraw their consent. With respect to text messages and other communication methods with a limited number of characters, subsection 2(2) of the CRTC Regulations provides that the information may be posted on a Web page that is readily accessible by the person by means of a hyperlink set out in the message.

The information required for a request for consent was not indicated in the CEMs sent by 9118-9076 QUÉBEC INC. and 9310-6359 QUÉBEC INC, nor did they include a link to a Web page where the information could have been found.

Amount owing and summary of other conditions

As part of the undertaking, 9118-9076 QUÉBEC INC. and 9310-6359 QUÉBEC INC. jointly and severally agreed to pay $100,000 in compensation for the alleged violations. A $25,000 amount was paid to the Receiver General for Canada, in accordance with subsection 28(3) of the Act. An additional $75,000 amount will be paid out to 514‑BILLETS customers in the form of 7,500 discount coupons with a $10 value each.

In addition to this monetary compensation, 9118-9076 QUÉBEC INC. and 9310-6359 QUÉBEC INC. have agreed to put in place a compliance program. This compliance program includes the review and revision of current compliance practices, the development and implementation of corporate policies and procedures designed to ensure compliance with the Act, the delivery of employee training, the implementation of adequate disciplinary measures in the event of non-compliance with internal procedures, the establishment of a thorough complaint monitoring and resolution structure related to CEMs sending, as well as various other monitoring and audit measures, such as mechanisms for reporting to CRTC staff concerning the program’s implementation.

This undertaking fully resolves all alleged or potential liability of 9118-9076 QUÉBEC INC. and 9310-6359 QUÉBEC INC. with respect to all CEMs sent by them or on their behalf from 1 July 2014 to the date of this undertaking.

So the published $100,000 was actually a $25,000 financial penalty, and $75,000 issued in discounts… to, one assumes, the very same people they were spamming to become customers in the first place.

Remember recently, how Tim Hortons engaged in egregious privacy violations and proposed that it give customers a free coffee and a donut rather than any, shall we say, meaningful penalty?

That seems to be where the Tim Hortons matter landed, per this Superior Court of Quebec decision of September 2022.

Of note in that decision is what I’d say is some extremely valid criticism of these kinds of arrangements – [s50]: “It has been said that they provide benefits to the companies being sued which runs afoul of the objective to deter harmful behaviour. Other objections include the low take-up rate of coupons, the fact that compensation may be tied to a purchase obligation, undue restrictions on the use of coupons and the high fees claimed by class counsel.”

This is enumerated in a series of factors that the court should consider with coupon-based compensation schemes:

2022 QCCS 3428, s52

Hyperlinks amended to the text of the decision’s footnotes rather than CanLII footnotes for the reader’s convenience.

[52] This being said, these types of settlements may be appropriate in certain circumstances. The following factors, while not exhaustive, should be weighed when a court is asked to consider whether a coupon settlement is fair, reasonable and in the best interest of members:

52.1. The individual value of the settlement: When the individual value of the settlement is low, it is often impractical or too costly to issue cheques or proceed with Interac transfers. In such cases, a coupon may be preferable to a cy-près payment which would not directly benefit class members.

52.2. The possibility to choose other compensation or to transfer the voucher: Courts are more likely to approve coupon settlements where the agreement provides that members may choose between coupons and other compensation, or when the coupon is transferable.3Abihsira c. Stubhub inc., supra, note 10, paras. 45 b) and d); Hurst c. Air Canada, 2019 QCCS 4614, para. 29; C. PICHÉ, supra, note 11, pp. 38 and 39.

52.3. The value of the coupon in proportion to the cost of redeeming it: When the good or service offered requires a subjectively important investment, some members may be indirectly forced to forego their compensation due to lack of financial means. On the other hand, when the settlement consists of a free item without further obligation or a rebate on a product or service that class members already use, credits may be the best way to automatically compensate members.

52.4. The likelihood that the coupons will be redeemed: Voucher settlement may be particularly problematic when access to compensation requires that customers purchase goods or services that may not be needed in the immediate future.4 Abihsira c. Stubhub inc., supra, note 37, para. 44 h). As such, the frequency and recurrence of the commercial relationship between defendant and class members may be an important factor to consider. One must also be wary of forcing customers to re-establish a long-term commercial relationship that the customer may now consider objectionable as a result of the complained-about practice.

52.5. Restrictions or conditions that apply: The easier it is to use the credit, coupon, or voucher, the likelier it will be that the settlement will be approved.5 Ibid, para. 44 a); Preisler-Banoon c. Airbnb Ireland, 2020 QCCS 270, paras. 34 to 35 (closing judgment 2021 QCCS 15); Gosselin c. Loblaws inc., 2019 QCCS 3941, para. 24; Jacques c. 189346 Canada inc. (Pétroles Therrien inc.), supra, note 12, para. 15. Coupon settlements that place undue restrictions or too short a time frame for the redemption of class member compensation should be frowned upon. When compensation requires a purchase or travelling to defendant’s establishment, the number and geographical availability of these locations or the possibility of conducting remote transactions is an important factor.

52.6. A change of practice: A coupon settlement may be considered more appropriate when the settlement is accompanied by an undertaking by the defendant to change the commercial practice which gave rise to the class action.6 Picard c. Ironman Canada inc., supra, note 28, para. 55; Abihsira c. Stubhub inc., supra, note 10, para. 44 j); Preisler-Banoon c. Airbnb Ireland, supra, note 39, para. 33.

52.7. The obligation to provide a report on the implementation of the settlement: The undertaking to provide the court with a detailed report on the redemption rate is considered to be illustrative of class counsel’s intent to ensure that as many members as possible will redeem their coupon.7 Hurst c. Air Canada, supra, note 37, para. 33; Gosselin c. Loblaws inc., supra, note 39, para. 30. This will especially be the case when the report is presented prior to the approval of class counsel fees.

52.8. Financial means of the defendant: When compensation to class members is deferred, the court must be satisfied that the defendant will be able to honour the coupon or voucher when it is presented.8 Abihsira c. Stubhub inc., supra, note 10, para. 44 f).

Other than that, this is a pretty open-and-shut violation: spam texts, with little sender and no unsubscribe / consent withdrawal information, clearly violating Section 4 of the regulations.

The decision seems… inexplicable in isolation, but with other prior decisions, such as the Blackstone one that AMPs should be lowered arbitrarily for small businesses, it does seem like the CRTC / CASL has the ability to adjust decisions in ways that may seem baffling to the casual observer. It’s hard to figure out what $75,000 in issued coupons is “worth” in terms of tallying penalties. It’s definitely not a $75,000 loss to the company. If I use an admittedly pretty arbitrary sourced redemption rate of 7%, it comes out to $5,250 out of pocket, which I’ll go forward with.

Issued penalty: $100,000

Final penalty: $30,250

Total issued AMPs: $2,317,000

Total imposed AMPs/monetary penalties: $853,250

Differential: $ 1,463,750

July 11, 2018

$250,000 in AMPs against Datablocks Inc. and Sunlight Media Network, Inc. (rescinded)

At this point, I’ll admit it:

I’m lost.

Part of the point of this was to track what the CRTC is saying it’s done, and what it’s actually done, because the announced penalties under CASL seem to be staggeringly high compared to the totals. I’m’a carry on, but situations like this one make it very challenging to keep track of what the CRTC claims has been done and what it’s tallying toward the “score.”

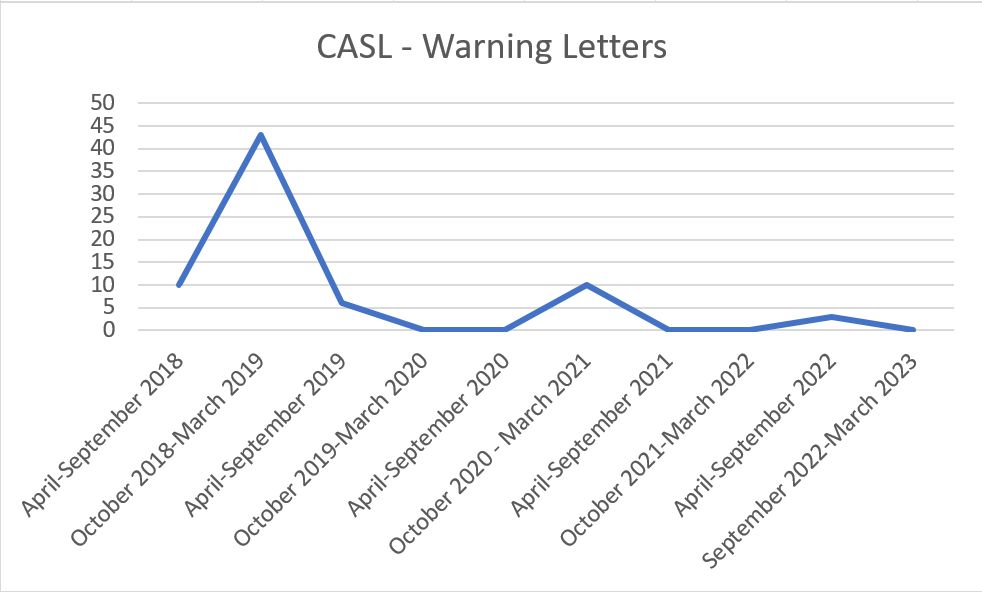

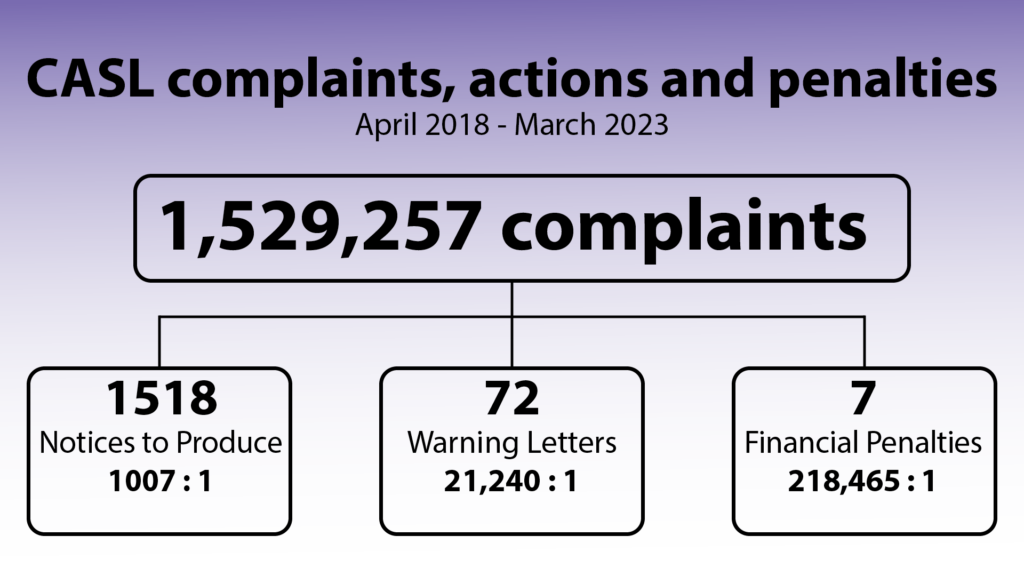

In its most recent enforcement snapshot, it states:

Payments and Penalties Under CASL

Since CASL came into force in 2014, compliance and enforcement efforts have resulted in administrative monetary penalties9A person who is served with a Notice of Violation has the opportunity to make representations to the Commission with respect to the amount of the penalty or the alleged violations. As such, any case brought to the Commission is subject to a review. (footnote theirs) and undertakings totalling over $3.6 million. (emphasis mine)10“Enforcing Canada’s Anti-Spam Legislation, Actions carried out by the CRTC between October 1, 2022 and March 31, 2023,” https://crtc.gc.ca/eng/internet/pub/20230331.htm

I’m not caught up yet – there’s still a few decisions from 2019-22 left to go – but I’ll tell you right now it’s not going to be even a fraction of $3.6 million in imposed penalties. Spoiler alert: we’re barely going to crack a million.

I’m going to keep gamely tracking decisions like this as part of the overall tally which theoretically will lead to that $3.6 million, but the math behind these pronouncements is getting increasingly baffling.

Anyhow.

The Datablocks/Sunlight Media decision is highly complex, and unlike all CASL enforcement to date orients around subsection 8.1 of the Act:

CASL Subsection 8.1

Installation of computer program

• 8 (1) A person must not, in the course of a commercial activity, install or cause to be installed a computer program on any other person’s computer system or, having so installed or caused to be installed a computer program, cause an electronic message to be sent from that computer system, unless

o (a) the person has obtained the express consent of the owner or an authorized user of the computer system and complies with subsection 11(5); or

o (b) the person is acting in accordance with a court order.

The gist of it is an accusation that Sunlight Media (operating an online ad network) and Datablocks (software/routing infrastructure), ran domains that redirected Government of Canada computers to a site that used Adobe / Shockwave Flash 11now there’s a specific nostalgic hit for nerds of a certain age exploits to install malware on the Government of Canada computers.

The infected computers were all promptly re-imaged without collecting any data on the malware, so there was no evidence of this after the fact [s39-47, 51]; further, the Commission noted that given IT processes it was plausible that the Flash files would have been blocked prior to installation [s69].

So it was dropped.

One thing to note here is the scope of this NOV and decision seems to be restricted to specific Government of Canada computers, while the initial investigation (now offline, archived here in the Wayback Machine) doesn’t mention this limitation of scope at all — the Government of Canada doesn’t get mentioned once in the body of the investigation, which talks about “malvertising” as a general scheme. It’s unclear how the scope of the violation narrowed from presumably a broad scheme to promulgate malvertising across the Internet to a few government computers.

Another thing of note is the clarification that malware must be successfully installed for a violation to occur – an attempt to install malware apparently doesn’t trigger CASL 8.1:

[s53] The Commission notes that subsection 8(1) of the Act refers to the installation of a computer program, not an attempt to install one. If the intent of Parliament in writing the Act had been to cover attempts to install, it likely would have included that language in subsection 8(1) of the Act. Furthermore, contrary to certain arguments made on the record, the issue is not necessarily about the infection, or compromise, of a computer system, since those actions or consequences are not referred to in the Act. The question is whether there is sufficient evidence on the record of the proceeding to conclude, on a balance of probabilities, that the Shockwave Flash Files listed in the NOVs were installed. (emphasis mine)

Issued penalty: $250,000

Final penalty: $0

Total issued AMPs: $2,567,000

Total imposed AMPs/monetary penalties: $853,250

Differential: $ 1,713,750

- 1Side note: It’s curious that William Rapanos is a “Toronto-area” man at the time of filing, and there’s a 2014 investigation against a Sharon Rapanos of Bowmanville, in the GTA. I can’t find an evident connection between the two, but it’s not a common last name. The NTP for Sharon Rapanos was a demand to produce the names of anyone who had access to her Internet from July 2014 to June 2015, and given William’s reliance on “I was hacked” as his defense above, there seem to be some dots that can be connected. Or not. The universe is big and full of coincidences.

- 2I get curious about things, so looked up “Ghazan Halazon” on LinkedIn, and found two profiles — the first, “dealfindingghazanhalazon” is the CEO of Couch Commerce, still lists Ghazan Halazon as its CEO, but there’s a second Ghazan Halazon, with an identical education background, but who mysteriously doesn’t mention Couch Commerce at all. Does this count as two?

- 3Abihsira c. Stubhub inc., supra, note 10, paras. 45 b) and d); Hurst c. Air Canada, 2019 QCCS 4614, para. 29; C. PICHÉ, supra, note 11, pp. 38 and 39.

- 4Abihsira c. Stubhub inc., supra, note 37, para. 44 h).

- 5Ibid, para. 44 a); Preisler-Banoon c. Airbnb Ireland, 2020 QCCS 270, paras. 34 to 35 (closing judgment 2021 QCCS 15); Gosselin c. Loblaws inc., 2019 QCCS 3941, para. 24; Jacques c. 189346 Canada inc. (Pétroles Therrien inc.), supra, note 12, para. 15.

- 6Picard c. Ironman Canada inc., supra, note 28, para. 55; Abihsira c. Stubhub inc., supra, note 10, para. 44 j); Preisler-Banoon c. Airbnb Ireland, supra, note 39, para. 33.

- 7Hurst c. Air Canada, supra, note 37, para. 33; Gosselin c. Loblaws inc., supra, note 39, para. 30.

- 8Abihsira c. Stubhub inc., supra, note 10, para. 44 f).

- 9A person who is served with a Notice of Violation has the opportunity to make representations to the Commission with respect to the amount of the penalty or the alleged violations. As such, any case brought to the Commission is subject to a review. (footnote theirs)

- 10“Enforcing Canada’s Anti-Spam Legislation, Actions carried out by the CRTC between October 1, 2022 and March 31, 2023,” https://crtc.gc.ca/eng/internet/pub/20230331.htm

- 11now there’s a specific nostalgic hit for nerds of a certain age