This is part four of a multi-part series reviewing Canada’s Anti-Spam Legislation in practice since its introduction in 2014 and the beginnings of enforcement in 2015. Crosslinks will be added as new parts go up.

Part 1: Terminology

Part 2: Parameters

Part 3: Big Numbers

Part 4: Case File – Compu-Finder

Part 5: Case File Anthology, 2015-2016

Part 6: Case File – Blackstone Education

Part 7: Case File Anthology, 2017-2018

Part 8: Case File – Brian Conley/nCrowd

Part 9: Case File Anthology, 2019-2022

Part 10: NOV – Sam Medouini

Part 11: Wrap-Up

Core resources:

The Act

Enforcement Actions Table (CASL selected)

As we get into cases resulting in AMPs, if there’s a theme here, I think it will be in establishing a prism of views on CASL: its effectiveness as a practical deterrent, its effectiveness as an educational tool, and how the marketing of CASL reflects the government’s (and our) view on the value of spam control vs. the panoply of other issues facing society today.

As somebody in marketing at the time, it’s hard to underestimate how vaguely scary CASL was for people who relied on email for marketing. The day CASL came into force as also _my_ first day on the job in higher ed marketing, having transitioned from almost a decade in for-profit marketing work, mainly in the pharma / CPG / health product sectors.

So I was cutting my teeth in higher education, a sector with a heavy reliance on email marketing, while CASL took shape. My higher ed marketing career has evolved concurrent with CASL, and it’s interesting to look at how my own views on it have evolved.

The following captures the anxiety and situation well just before the law came into force:

“When CASL comes into force on July 1, 2014, it will be one of the most demanding laws in the world dealing with CEMs. The requirements that recipients specifically opt-in to receiving CEMs and CASL’s classification of electronic requests for express consent CEMs themselves, combined with the potentially enormous financial penalties for breaching the legislation make CASL particularly daunting for businesses sending messages to or from Canada.

It is impossible to know at this point how strictly CASL will be enforced, and the severity of fines that will be issued for infractions.”

Moving from that quote alone, we have a few areas for follow-up:

- how closely is the requirement that recipients specifically opt into CEMs followed?

- what are the financial penalties that have been levied, and have they been followed through on?

- has the legislation worked, in the raw sense of whether or not spam is in fact being curbed?

The latter question is at least answerable through statistics — see this earlier post.

The straightforward answer to “Did CASL work?” depends on how you define its goal. We can start with the stated purpose from the Act itself:

Purpose

Purpose of Act

3 The purpose of this Act is to promote the efficiency and adaptability of the Canadian economy by regulating commercial conduct that discourages the use of electronic means to carry out commercial activities, because that conduct

(a) impairs the availability, reliability, efficiency and optimal use of electronic means to carry out commercial activities;

(b) imposes additional costs on businesses and consumers;

(c) compromises privacy and the security of confidential information; and

(d) undermines the confidence of Canadians in the use of electronic means of communication to carry out their commercial activities in Canada and abroad.

“CASL hasn’t stamped out spam, and complaint rates remain relatively consistent, so it is not successful” is a defensible position, but per the Act itself, it is achieving its purpose as stated: to regulate commercial conduct and discourage communications that do a number of things that amount to what we think of as spam.

And even from the jump, reaction to the Act was mixed at best.

It’s also worth noting that the organization that enforces the law is also the one that gathers the complaints.

Which makes sense: the police get calls about people breaking the law, and enforce the law. The fire department gets the calls about fires and then puts out the fires. There’s no disconnect in the process, but it does leave a certain amount of latitude in terms of letting one body both define the problem and attempt to resolve it.

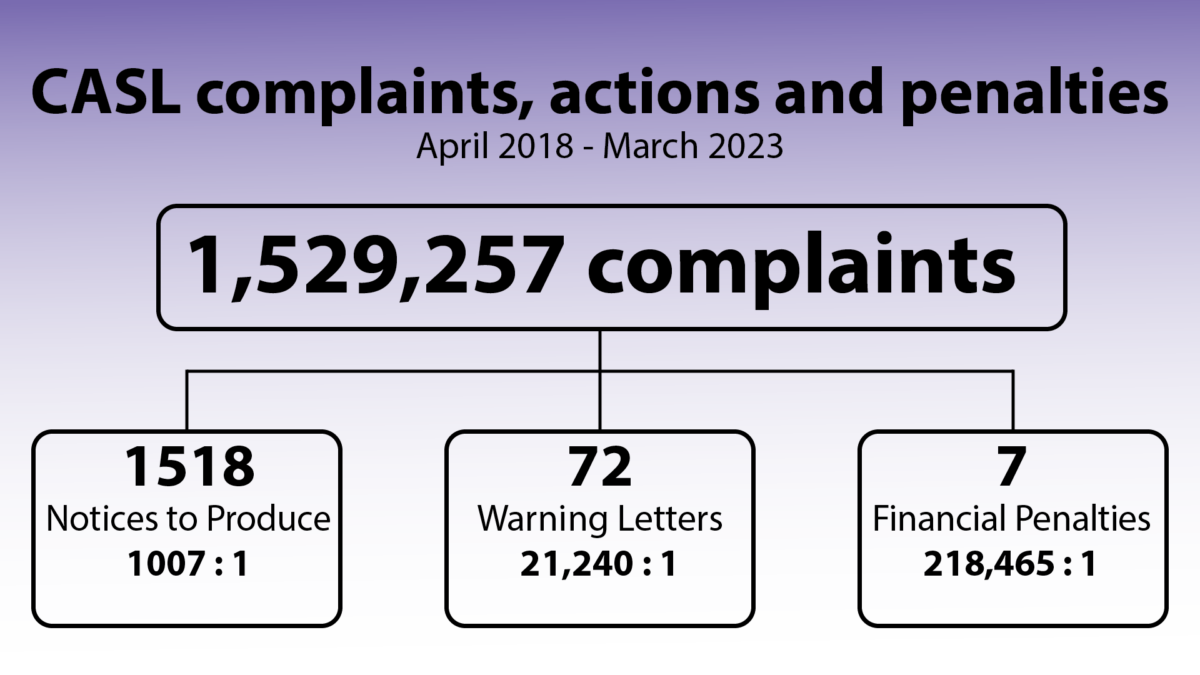

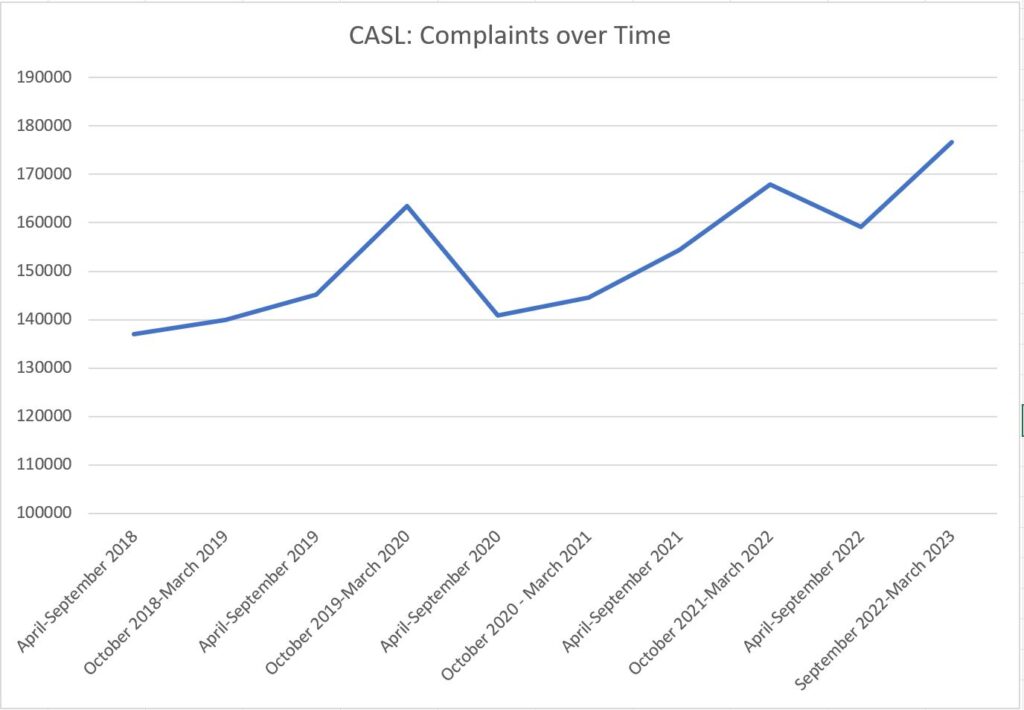

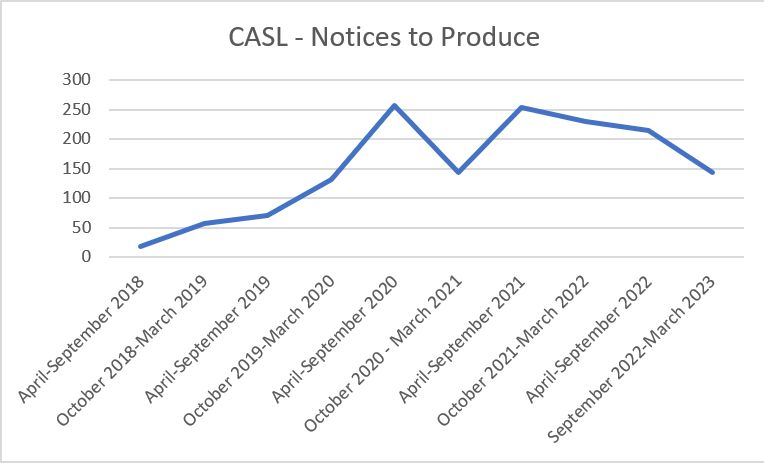

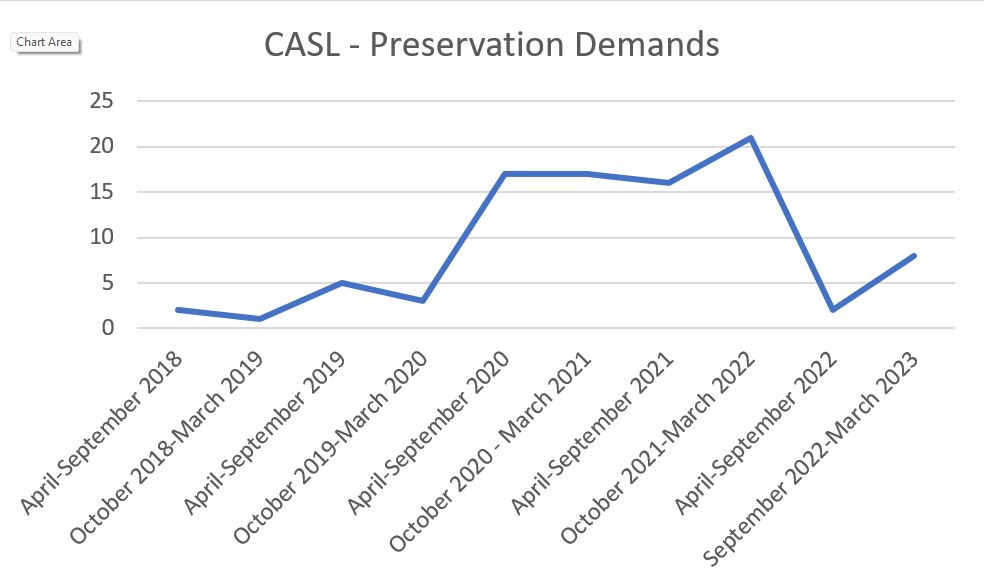

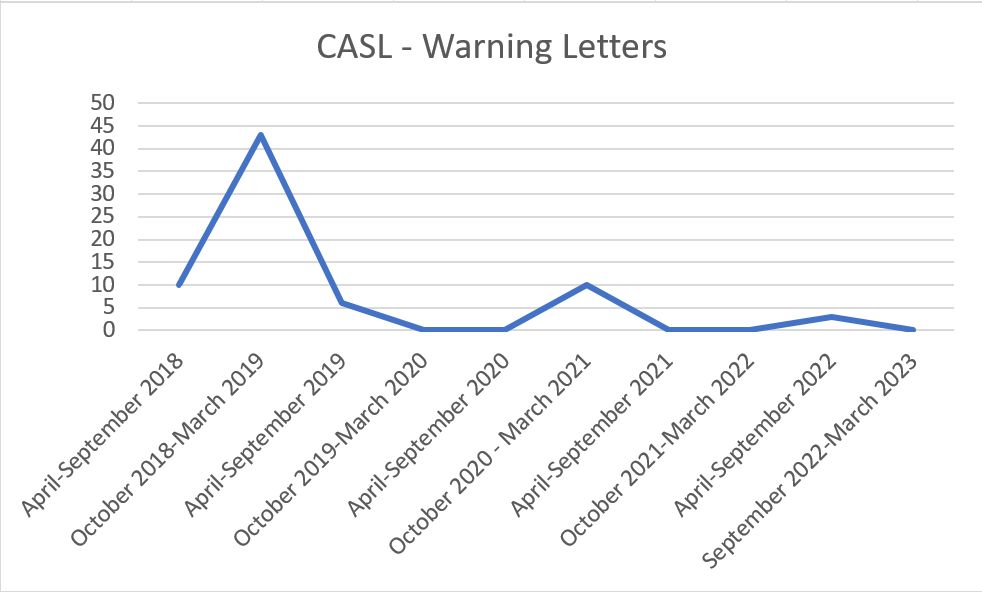

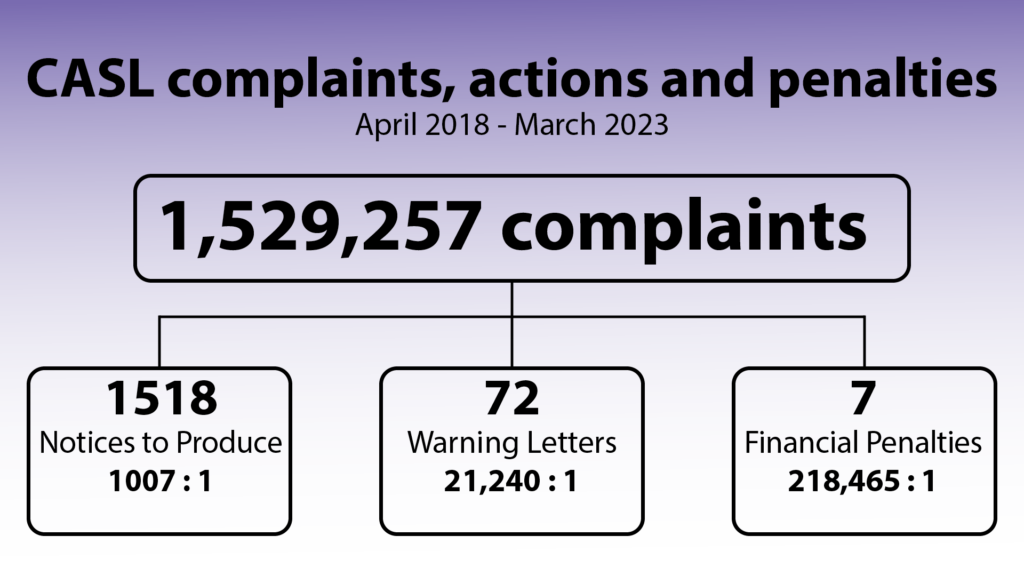

As mentioned in the statistical breakdown, the ratio of complaints to actions — be it requests for information, warnings, or eventually compliance actions — is immense. And the number of actual decisions is small, and the number of AMP penalties even smaller.

Small enough that one person can look at each of them in turn. We’ll start with one that got national headlines at the time: back in 2015, a $1.1 million AMP levied against Compu-Finder.

Here’s the 2015 decision.

This drew national headlines as a definitive warning shot to violators of the new law.

What happened?

In a nutshell: Compu-Finder sent out a lot of unsolicited email without an adequate unsubscribe mechanism, which is pretty blatantly in violation of the law (and also — for anyone in marketing – not smart. Seth Godin wrote Permission Marketing in 1999, for Pete’s sake… this, even absent legislation, violated a lot of common sense and best practices).

The Notice of Violation is so brief that I can fit it all right here, in an accordion (fold out to view):

2015 AMP for Compu-Finder

Ottawa, 5 March 2015

File Nos.: 9094-2014-00302-001

To: 3510395 Canada Inc. (dba Compu.Finder)

Name: Ms. Sylvie Pagé, President

Address:

707, chemin du Village, suite 202

Morin Heights, QC, J0R 1H0

Issue Date of Notice: 5 March 2015

Penalty: $1,100,000

Pursuant to section 22 of the Act to promote the efficiency and adaptability of the Canadian economy by regulating certain activities that discourage reliance on electronic means of carrying out commercial activities, and to amend the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission Act, the Competition Act, the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act and the Telecommunications Act, S.C. 2010, c. 23 (the Act), the undersigned has issued this notice of violation finding 3510395 Canada Inc. to have committed the following violations contrary to Paragraphs 6(1)(a) and the Act:

Between 2 July 2014 and 16 September 2014, inclusively, 3510395 Canada Inc. sent or caused or permitted to be sent, to electronic addresses, commercial electronic messages, in three (3) patterns, without having the consent of the persons to whom the messages were sent, resulting in three (3) violations of section 6(1)(a) of the Act.

Between 2 July 2014 and 16 September 2014, inclusively, 3510395 Canada Inc. sent or caused or permitted to be sent, to electronic addresses, commercial electronic messages, containing an unsubscribe mechanism that did not function properly, resulting in one (1) violation of paragraph 6(2)(c) of the Act. Contrary to paragraph 6(1)(b) of the Act, 3510395 Canada Inc. did not ensure that the unsubscribe mechanism was valid for a minimum of 60 days after the message was sent, in accordance with subsections 11(1)(b) and 11(2) of the Act and as required by paragraph 6(2)(c) of the Act, or 3510395 Canada Inc. did not give effect to an indication sent in accordance with subsection 11(1) without delay, and in any event no later than 10 business days after the indication was sent, without any further action being required on the part of the person who so indicated, as required by subsection 11(3) of the Act.

Pursuant to section 20 of the Act, the undersigned has determined that the total administrative monetary penalty for the violations identified above is $1,100,000.

The penalty of $1,100,000 must be paid by 3510395 Canada Inc. to “The Receiver General for Canada” in accordance with subsection 28(3) of the Act.

Manon Bombardier

Chief Compliance and Enforcement Officer

The widely reported decision was a wake-up call for marketers from coast to coast in Canada. Over a million dollars? For 3 email campaigns? In a miasma of still not being entirely rock solid on how the law worked, and how aggressively it would be enforced, especially in the soft areas around what constituted a “business relationship,” it was pretty scary stuff.

Other investigations and a walking-back of the $1.1M

In 2016, the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada carried out its own investigation, using submissions and reports from the CRTC/CASL: PIPEDA Report of Findings #2016-003: Investigation into the personal information handling practices of “Compu-Finder” (3510395 Canada Inc.) – Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada It was clear that the PIPEDA investigation is distinct from CASL [114].

Some interesting nuances in that investigation:

- While addresses were harvested before the Act introduced provisions regarding address harvesting on July 1, 2014, use of some of those addresses still constituted a violation of the Act [16].

- The volume of complaints to the SRC was 1,015 over a nine-months-plus-a-bit period. That’s over 100 complaints a month, which is a lot of complaints. Reading between the lines – if people were submitting that many complaints to a government body, surely Compu-Finder must have been getting a ton, enough that I’d hazard they were being deliberately obtuse about it. Again – permission marketing wasn’t a new concept, even in 2014. [27]

- Ultimately, 317 emails were at issue; ultimately this averages out to about 100 emails per “pattern” of email. Only 87 violated the unsubscribe requirement. [31]

- The emails came from a revolving door of domain names, including “coursacf”, “acfmanagement”, formationacf”, “objectifscommerciaux”, “gestionnaireschan, “laformationsenligne” and “moncourtravailz” – “to name a few,” as stated in the investigation. They were also sent / signed by generic names such as “Team Leader,” “Director General,” etc. [29,30]

…honestly, the investigation is worth reading. It feels like Compu-Finder missed a trick in not opening a highly profitable red flag factory.

Lack of meaningful consent, ambiguous phone scripts to cold-call companies and extract names and email addresses, reliance on implied consent (PIPEDA 4.3.6; PIPEDA 40.1) but disregarding express prohibitions against solicitation in public email directories… if I were to write a Goofus and Gallant children’s book on e-mail marketing in Canada, the Goofus pages are fully filled in.

Ultimately, Compu-Finder agrees to implement the OPC’s mandated changes “without prejudice and without admission.” [156]. The OPC determines that the issues are either well-founded and resolved, or well-founded and conditionally resolved, noting that the Office has a “continuing interest” in making sure Compu-Finder is compliant. [160, 161]

Then, in 2017, the CRTC walked back on the $1.1 million, dropping it to $200,000.

Which is still more money than most organizations would care to spend on a fine for spam, but a pretty huge leap back from the national-headline-grabbing over-a-million amount. Why? The reasoning extends across [87] through [124] of the decision, culminating in

[125] The Commission finds, on a balance of probabilities, that Compu-Finder committed the four violations set out in the notice of violation, and imposes a total penalty of $200,000 on the company.

So why was there apparently a $900,000 error in the first decision? This may seem cynical, but as somebody who works in marketing, the one line that that review that leaps out as pretty close to an admission that they did it for the shock and awe is here:

[92] The investigation report stated that the purpose of the penalty, being the promotion of compliance with the Act, was achieved through general deterrence created by the AMP, and that the proposed penalty was not disproportionate to the violations. (emphasis added)

The decision, in [87-124], covers ground including the offense, Compu-Finder’s ability to pay, whether or not the size of the penalty triggers a s11 Charter violation (more on constitutional challenges later), and proportionality.

It is what it is; but one might expect that the CRTC would have worked through all of this before issuing the AMP in the first place, unless the object was to terrify as opposed to impose a fee that sticks.

In a 2020 decision — and let’s remember that this all started back in November of 2014 — 3510395 Canada Inc. v. Canada (Attorney General), 2020 FCA 103 (CanLII), [2021] 1 FCR 615 saw the FCA roundly deny Compu-Finder’s appeal, in a decision that covered a substantial amount of ground.

I’m going to refer heavily here to a summary by Ryan J. Black, Becky Rock, Tyson Gratton & Meghan Bellstedt, then of DLA Piper (Canada) LLP, available on CanLii, and worth reading on its own. The FCA decision:

- established that CASL is constitutionally valid federally (among other things this prevents “legislation shopping” among provinces for the one with the least stringent anti-spam legislation)

- doesn’t violate Sections 7, 8 or 11 of the charter (the first because there’s no unreasonable seizure in a CASL request, the latter two because there’s no criminal charges or penal consequences)

- justifiably violates S1 of the Charter, Freedom of Expression — of note, see Para 194 of the FCA decision and its statement that “commercial expression is not as jealously guarded as some other forms of expression”.

Compu-Finder then sought leave to bring this to the Supreme Court, and was rebuffed in March of 2021, six and a half years after the initial ruling.

We won’t be covering further decisions in this much detail, but out of the gate Compu-Finder establishes a few modes of action that are worth tracking:

- Big-money AMPs that are later reduced

- CASL decisions that get walked back by the CRTC later on

- Targeting offenders that operate mainly in the private sector, and mainly in tech

On that first bullet, here’s the beginning of a running tally:

Issued penalty: $1,100,000

Final penalty: $200,000

Differential: $900,000

Let’s dive into a few more of these, and see where and when that pattern holds, and how those numbers differ over time.

Incidentally – Compu-Finder seems to have fallen on hard times since the Supreme Court’s rebuffing. At the time of writing, of the URLs identified in the PIPEDA investigation in 2016 as being the principal URLs for Compu-Finder have all fallen on hard times:

- compufc.com – 404 error

- acfmanagement.com – returns a blank page; View Page Source shows only a notification to enable JavaScript but not indication of what the content would be

- prosperer.ca – clearly abandoned; there is content on the page but the CSS is broken and the page is unreadable

- academiedegestion.com – redirects to an alphabet soup URL that requires you to allow notifications to view it – no thank you.