This is part eleven of a multi-part series reviewing Canada’s Anti-Spam Legislation in practice since its introduction in 2014 and the beginnings of enforcement in 2015. Crosslinks will be added as new parts go up.

Part 4: Case File – Compu-Finder

Part 5: Case File Anthology, 2015-2016

Part 6: Case File – Blackstone Education

Part 7: Case File Anthology, 2017-2018

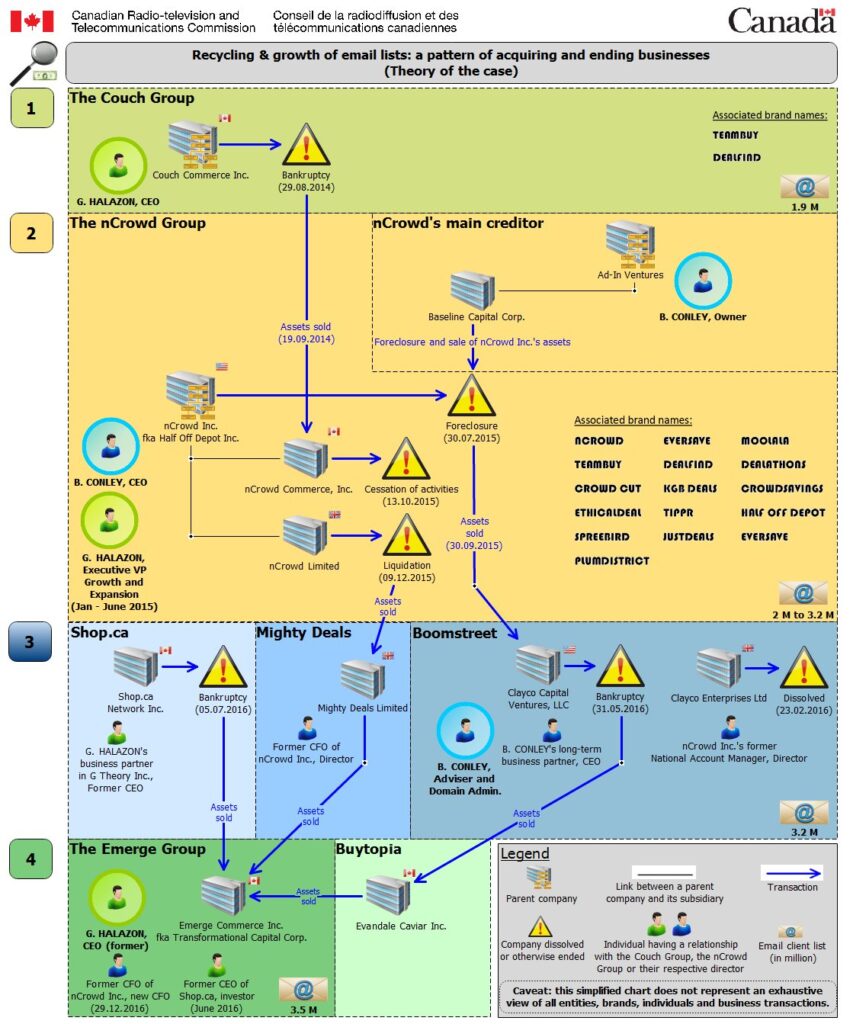

Part 8: Case File – Brian Conley/nCrowd

Part 9: Case File Anthology, 2019-2022

Core resources:

Enforcement Actions Table (CASL selected)

Here it is.

I’ve been taking various runs at a wrap-up of almost 10 years of CASL being on the books, and keep kind of bouncing off this summary. In part because it’s hard for me – as somebody who needs to interpret the regime, but who is also interested in looking at its effects over time – to get a firm grip on how it is implemented and practised based on the last 9-and-a-bit years of enforcement.

I’m going to break this down into a few components:

- Useful things to know, that are in the Act but may not jump out at a user;

- Specific observations based on notices of violation and CRTC rulings;

- A general overview of how I feel about CASL. Spoiler: conflicted.

General rules:

CASL isn’t just for “spam”. Frankly, they should rename it. “Anti-Spam legislation” is a snappy phrase but causes more confusion than is warranted. The conventional understanding of spam is junk email, but this legislation applies to texts, intrusive software (malware), browser extensions… essentially, if it’s delivered digitally, it falls into the remit.

ALL Commercial Electronic Messages (CEMs) are prohibited. By default. Assume any commercial message is not allowed to be sent, and CASL carves out exceptions to the general prohibition.

ANY CEM contaminates a non-CEM. Even if a message is 99% non-commercial, any inclusion of any content that – from the Act:

having regard to the content of the message, the hyperlinks in the message to content on a website or other database, or the contact information contained in the message, it would be reasonable to conclude has as its purpose, or one of its purposes, to encourage participation in a commercial activity, including an electronic message that

(a) offers to purchase, sell, barter or lease a product, goods, a service, land or an interest or right in land;

(b) offers to provide a business, investment or gaming opportunity;

(c) advertises or promotes anything referred to in paragraph (a) or (b); or

(d) promotes a person, including the public image of a person, as being a person who does anything referred to in any of paragraphs (a) to (c), or who intends to do so.

The Act, 1(2)

Requests for consent are also CEMs per s1.3 of the Act. This results in a Catch-22 – you can’t market without permission, but asking for permission is marketing. Added value is therefore key – or couching a consent request in an otherwise legitimate communication. I can’t email you out of the blue (except under a certain set of circumstances) asking you to opt into my newsletter, but I can post on LinkedIn telling people I’ve created a free white paper on best practices in Z, and require people to sign up for my newsletter to download that white paper.

Nuance that becomes clearer through decisions:

From Compu-Finder:

- You can’t obfuscate the source of emails by generating different “from” identities or sender identities. Swapping out domain names, or who the email appears to be sent from, is immaterial. The owner of the domain(s) is at issue, not the sending domain itself [29-30]

- Reported initial decisions are not final. It is always, always worth working with the CRTC, if you are one of the very rare organizations that gets to the point of having an AMP levied (see “CASL is your Old Testament God,” below). Explaining your context, pleading small-company-will-fail, and working with them to put a program in place to prevent future violations seems to be a foolproof way of getting AMPs reduced, sometimes very dramatically.

From Porter Airlines:

- Stating the obvious, but this is a little trifecta of consent, contact info, and unsubscribe functionality – all three have to be in place for you to be compliant with CASL. You can’t mix and match.

From Blackstone:

- A campaign is a violation, not an individual email. [2]

- There is no conspicuous difference in the scope of campaigns, given Blackstone and later Conley/nCrowd. One send of 100 emails is “as bad” as one send of 10,000 emails on the surface; there’s no pattern evident in the decisions that show scope-based penalties.

- You don’t need a price to have a CEM: if you’re offering a service and implying it costs something, that’s enough to pass a threshold of “commercial electronic message” [18]

- Somebody simply publishing an email address on the Internet isn’t enough to invite solicitation; if you are pulling addresses to create a list, keep records, as you still have to make a case-by-case justification of how consent is implied. As they say in the Act, ”the onus… rests with the person relying on it.” [25-28]

- As an example – and this is me extrapolating, not the legislation – I am on the Smith Engineering higher ed website as the Director, Marketing and Communications, with my email published. That makes me contactable as somebody you can email if you’re offering a product that impacts marketing and communications in higher education, but you’ll want a spreadsheet somewhere that captures that information as the reason you’re reaching out to me.

- I would argue that the “in higher education” component above is relevant and important, but given the overall pattern of how legislation is enforced (see again below) I think this is in the ‘jaywalking’ category of a distinction without a difference – it’s a fine point that could be argued pushes someone into the “spam” category, but likely too minor to be meaningfully enforced. That said, please don’t spam me.

From Ghassan Halazon:

- People can be pursued as individuals, which is detailed in the Act [s 32]. There is no clear line via decisions of when vicarious liability will be imposed; the Act states that explicitly in s 31:

- An officer, director, agent or mandatary of a corporation that commits a violation is liable for the violation if they directed, authorized, assented to, acquiesced in or participated in the commission of the violation, whether or not the corporation is proceeded against.

- To date there has been no “double dipping” where a corporation and a leader figure has been found in violation, but that doesn’t mean it will never happen.

From 514-Billets:

- The CRTC has been open, at least once, to alternate compensation schemes; rather than cutting a cheque to the Receiver General, 514-BILLETS issued coupons for 75% of the imposed penalty.

From Datablocks/Sunlight Media:

- While rarely, s 8.1 of the Act is enforced – it’s not clear on whether the relative scarcity of enforcement is because infractions are more rare, or cases are much, much more complex and harder to investigate and pursue.

- To wit, this “malvertising” case seems pretty damning on the evident facts, but poor documentation and an aggressive malware response policy within the Government of Canada made this not pursuable.

- This is obviously not an open invitation to do nefarious things with computers, but a user-level caution that if you intend to file reports on malware / intrusion software / etc., be slow and cautious about how you capture information and document it.

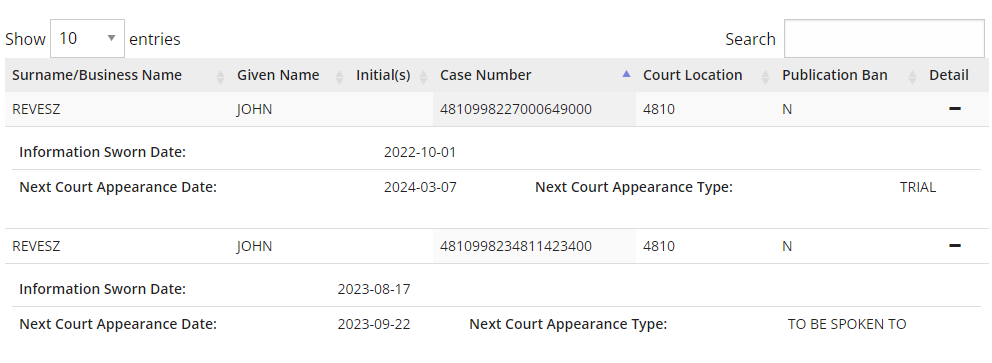

From Brian Conley / nCrowd:

- Again reading into the tea leaves of how the Act is enforced but it feels like vicarious liability is the recourse when it seems like companies aren’t going to be around long enough to pursue / there’s an evident pattern of MBA-style shell games.

- There are large and seemingly arbitrary gaps in penalties without much rationale provided for the differing amounts by the CRTC (see, again, the next section)

From Orcus Technologies:

- Vicarious liability [s 32 of the Act] is growing in use over time; either reflecting a greater focus on ephemeral companies, or an evolution in the CRTC’s understanding of what penalties will stick.

- There seems to be an awkward marriage between CASL and criminal penalties for cybercrime – CASL itself expressly does not have a criminal component, and the hand-off from the CRTC investigation to the RCMP / OPP seems to only, possibly, be resulting in a criminal process four years on.

From Scott William Brewer:

- Again, working with the CRTC seems to have a very high success rate in diminishing penalties – from $75,000 to $7,500 in this case.

The final tally

Who wants spreadsheets? We got spreadsheets.

Wuxtry! Wuxtry! Getcher spreadsheet heah!

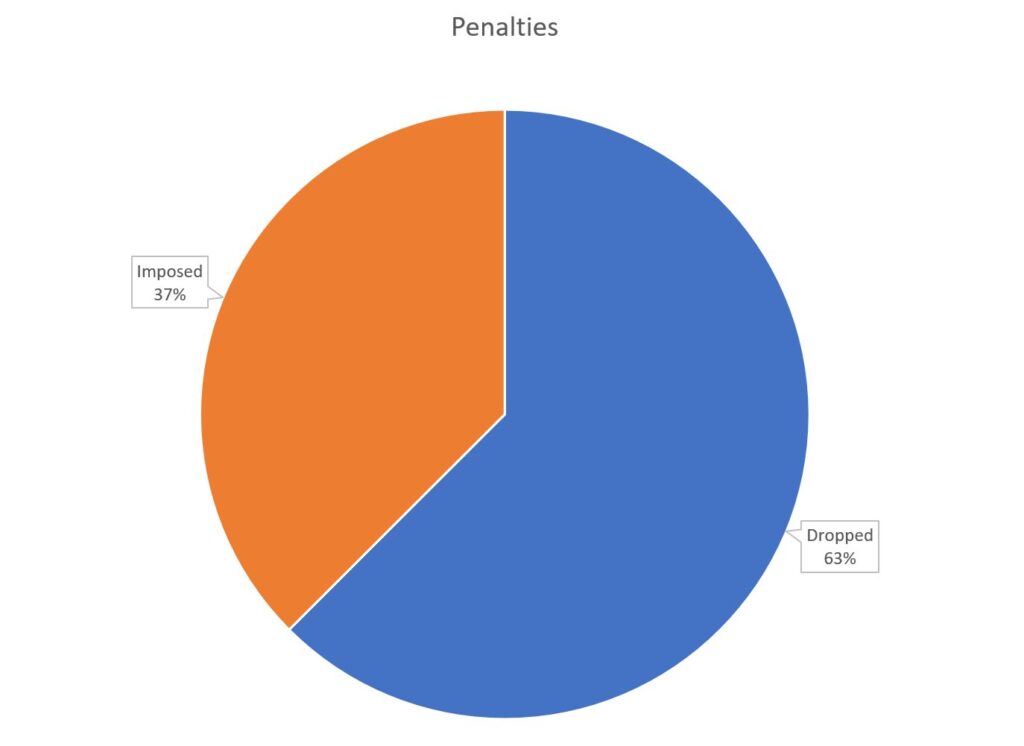

When I tabulate all issued penalties from decisions to date, I arrive at $3,163,000. Imposed penalties – admittedly with fuzzy math around coupon redemption rates for the 514-BILLETS issue – come in at $1,185,750.

The differential is $1,977,250 – about 63% of issued penalties wound up not being imposed. We’re also assuming that all imposed penalties were, in fact, paid – in several cases the companies that had imposed penalties then seem to have gone out of business, so the likelihood of the Canadian Government having seen that money is dim.

I also can’t account for about $500,000 that CRTC summaries say were imposed; more on that under “CASL as a marketing exercise,” below.

CASL as your Old Testament God

This kept running through my head as I tried to look at decisions and figure out if there was any clear logic to an external user regarding:

- Who was investigated and penalized; was there a consistency in terms of numbers of complaints, egregiousness of the action, or public visibility of the offender?

- When penalties were imposed, was there a clear line to draw regarding the severity of the penalty compared to the actual actions taken in violation of CASL?

As somebody raised in the church, the more I poked at it the more I felt I understood the terror of the, I don’t know, Hittites: there’s a baseline set of behaviours you’re expected to follow, but it’s impossible to know when the eye of judgment will fall upon you, and when it does, there’s no real way to predict the extent of your punishment.

- Blackstone somehow finds its way to a $590,000 reduction in penalty, despite Blackstone’s only engagement as described in the decision being to complain about a deadline, file an appeal to entirely the wrong court, and then not cooperate – the CRTC actually calls them out specifically for this in the final decision [s55].

- Conversely, some level of cooperation seems to have given Ghassan Halazon a $10,000 penalty for CEMs sent by Couch Commerce, but Brian Conley – not exactly his partner in crime, but certainly fellow traveller in terms of responsibility and scope – paid 10x as much, at $100,000.

Beyond those examples, it’s hard to know how evenly the law is applied – or even what the specific triggers and determinants of a penalty are. It doesn’t feel entirely random, but since most decisions are posted without the number of campaigns or scope of sends, there’s no way to draw a line from the violation to the penalty in a way that makes sense in terms of whether it’s being evenly applied.

CASL as a marketing exercise

The other thing is that the pattern of CASL actions – from the perspective of somebody that works in marketing – seems to be more about creating the impression of enforcement than consistently and rigorously applied penalties.

The most recent snapshot contained the following now-familiar text:

Payments and Penalties Under CASL

Since CASL came into force in 2014, compliance and enforcement efforts have resulted in administrative monetary penalties and undertakings totalling over $3.6 million.

I can’t account for these numbers: even the $3.6 million is $0.5M higher than a manual tally of NOVs from the CRTC site (I’ve made a spreadsheet).

My own numbers land at $3,163,000 in issued penalties, but only $1,185,750 in imposed penalties – about 37% of the issued penalties wound up being actually imposed.1The imposed penalties number does include a bit of my own math, as the 514-BILLETS case resulted in the issuing of $75,000 worth of rebates, which I calculated at far less than that value in terms of what the ultimate cost to the company would have been.

But there’s also a pattern of big shock-and-awe announcements that get quietly walked back after the fact, or that lead to follow-on penalties much smaller than the initial ones:

- A national-headline-grabbing $1.1M penalty for Compu-Finder, later reduced to $100,000.

- Similarly, significant hay made about Brian Conley being issued an NOV as “vicarious liability”, at $100,000, but then much smaller amounts for a similar breadth of issue by fellow traveller Ghassan Halazon and the completely unrelated William Rapanos.

- The “malvertising” case with Datablocks and Sunlight Media, which dropped a $250,000 penalty to nothing, while narrowing the scope of its investigation from the broad issuing of malvertising across the Internet to a lack of proof on specific Government of Canada computers.

A journey through CRTC CASL “Snapshots” show a pattern of reporting actions that weren’t actually taken under CASL – things done by the CRTC as a whole, but as far as I can tell unrelated to CASL or its enforcement.

For instance, in the most recent snapshot, headlines include:

- Large-scale Bank Phishing Investigation – a criminal investigation, following reports to CASL

- Using social media to warn Canadians – essentially, CRTC posted and retweeted about frauds

In the previous snapshot, the headlines are all about various CRTC activities – a CRTC decision regarding botnet blocking (its development being the sole headline of an earlier snapshot), a report on a Canadian “dark web marketplace” (actually a reference to the previous snapshot, and not new news) and vigilance over malware called QAKBOT.

And so on. I won’t blow-by-blow this, but if you go back through the snapshots, the bulk of reporting isn’t actually about CASL, but other CRTC activities.

This makes perfect sense from a certain perspective. If you’re a parent, or a teacher, or have ever run a volunteer organization, there are times when you have a rule that you can’t practically enforce, and for whatever reason the common good isn’t enough to get people to follow it. Telling people there is a rule, and enforcing it sporadically, but with harsh enough penalties that it scares everyone into compliance, makes a lot of sense.

Starting with the assumption that the CASL team is smart, works hard, and is just not adequately staffed to provide perfect enforcement nationally at all times (which would take a preposterous scaling-up), big penalty announcements with quiet walkbacks, trumpeting non-CASL achievements in a way that makes CASL look vast and vigorous, is a good move. In the day to day, risks of getting caught are relatively low (see below), but when $1M+ penalties are making the headlines, the idea of getting caught in that net is scary.

But is scary enough?

Does CASL work?

Back when I started this analysis, I said my interests were:

- establishing whether or not the overall rate of spam is going down

- gaining some understanding of the likelihood of a significant action being imposed on an organization

What have we learned?

Is spam going down?

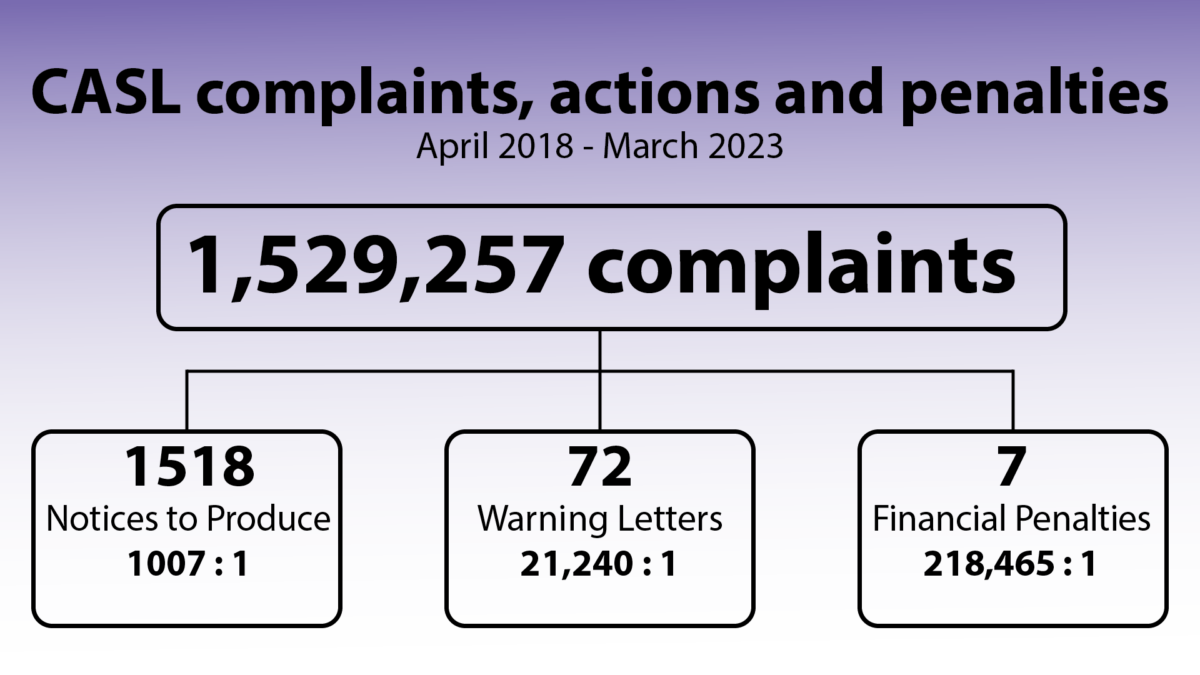

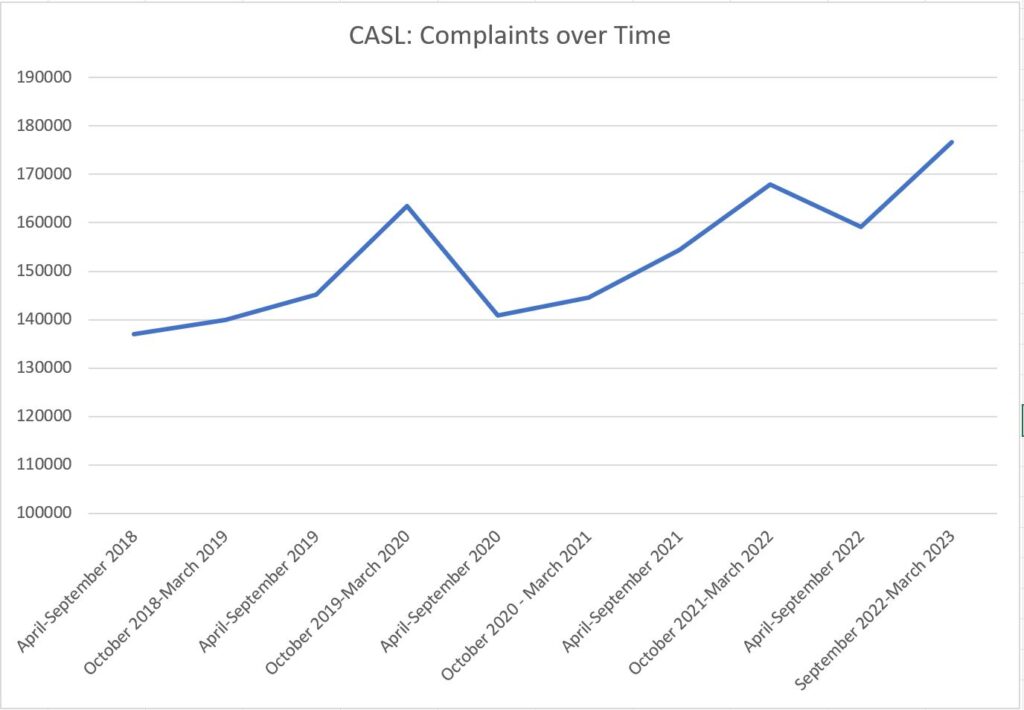

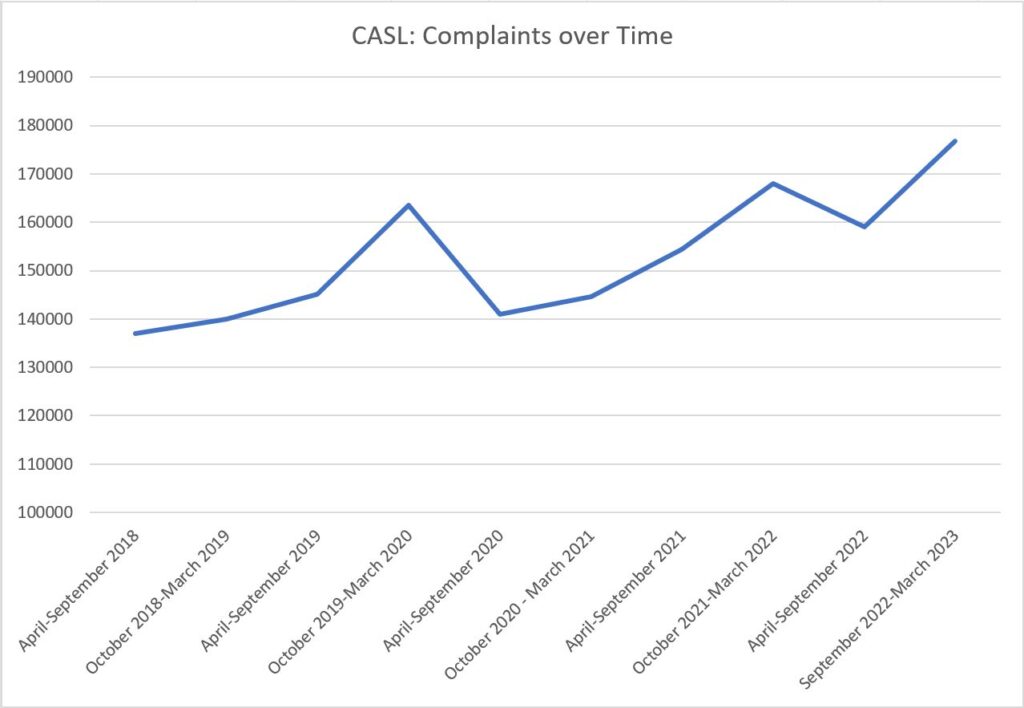

On the first front, the answer is clearly that complaints are not going down.

Arguably there are many reasons for this – including CASL’s own effectiveness in sensitizing the public to spam and fraud, driving reporting numbers up.

But – given the sporadic nature of enforcement, and the amount of fuzziness around what CASL is claiming, both in terms of penalties and its own vs. taking credit for other CRTC activity in its snapshot – I don’t have a great feeling about it.

Maybe it can’t “work”. Maybe the digital world is too big, and too global, and evolving too fast, for us to “beat” online fraud in any meaningful and lasting way, and stemming the tide is the best we can ever hope for. I don’t have the time or resources to really meaningfully compare CASL to other national spam protection regimes, so there aren’t any comparators out there I can easily index against.

It’s possible that looking at CASL through the same lens as other public-service organizations and criteria – is crime going down, as a measure of police effectiveness; wellness and death rates, as a measure of public health effectiveness – is a fool’s errand.

This leaves me with an aggregate shrug. Does CASL work? Shrug. Could it be doing better? For sure. Should we, as a society, allocate the kinds of resources to it that it would take to do better? Shrug.

But if my read of CASL actions, and their own snapshot headlines, is correct and the slow pivot is from enforcement to awareness, and there’s been a general slide from “we can stop this” to “our best chance is to educate the public, focus only on the worst offenders, and rely on private enterprise to develop better detection and protection algorithms,” that’s a big change over the last 10 years that’s never been explicitly acknowledged.

What’s the likelihood of specific action being taken?

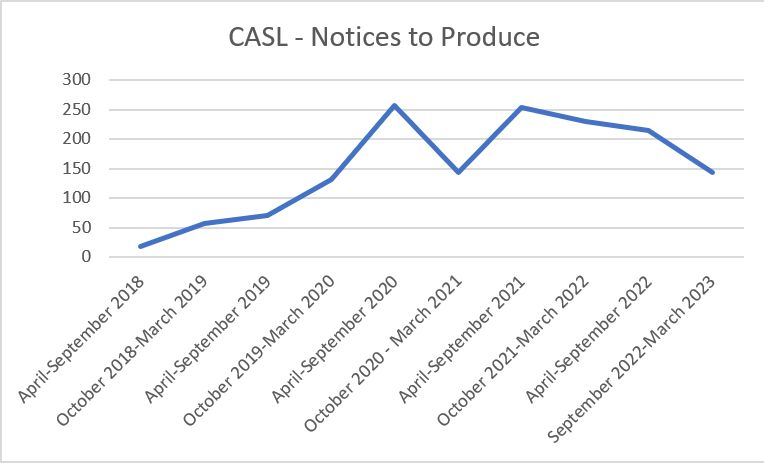

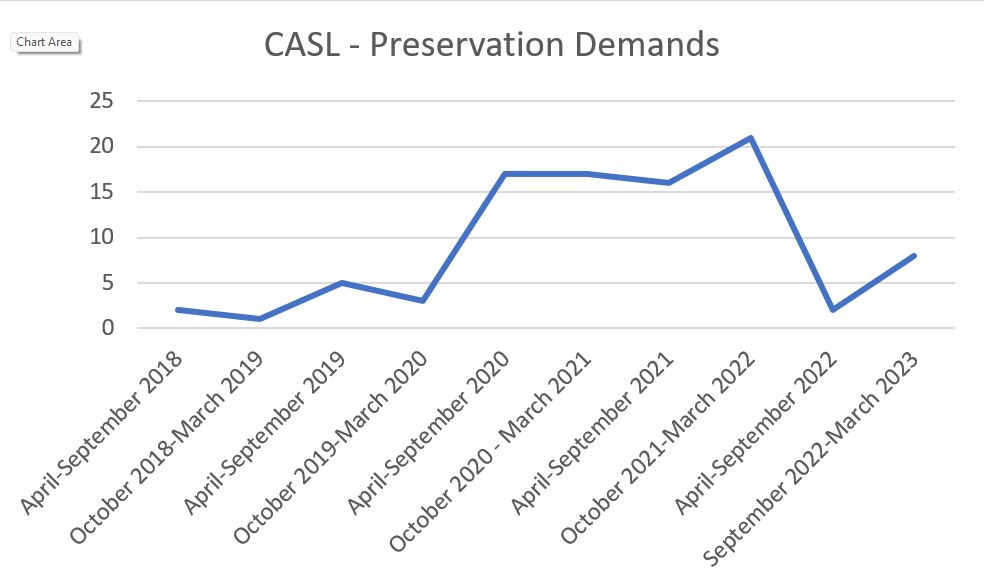

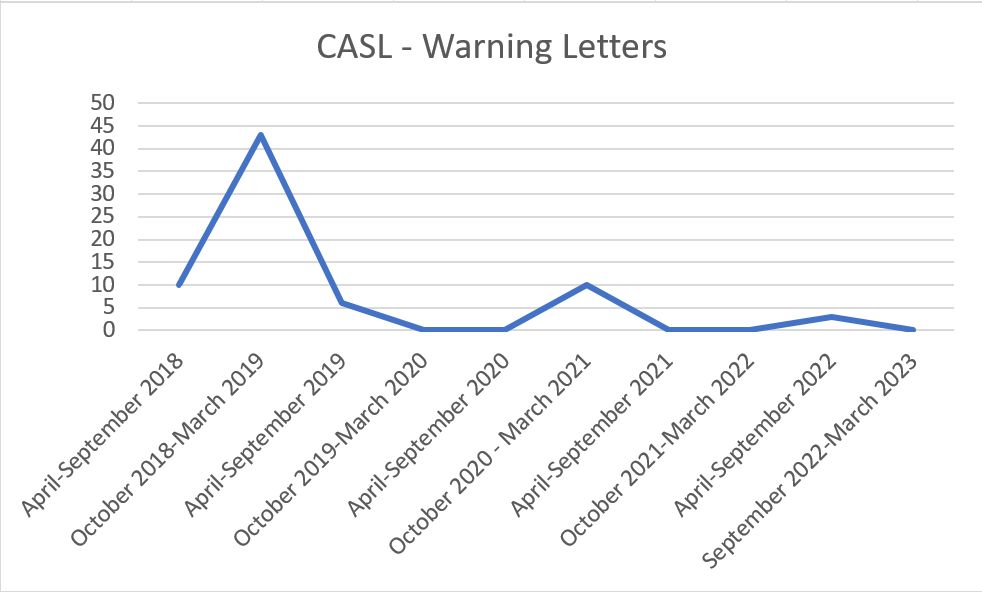

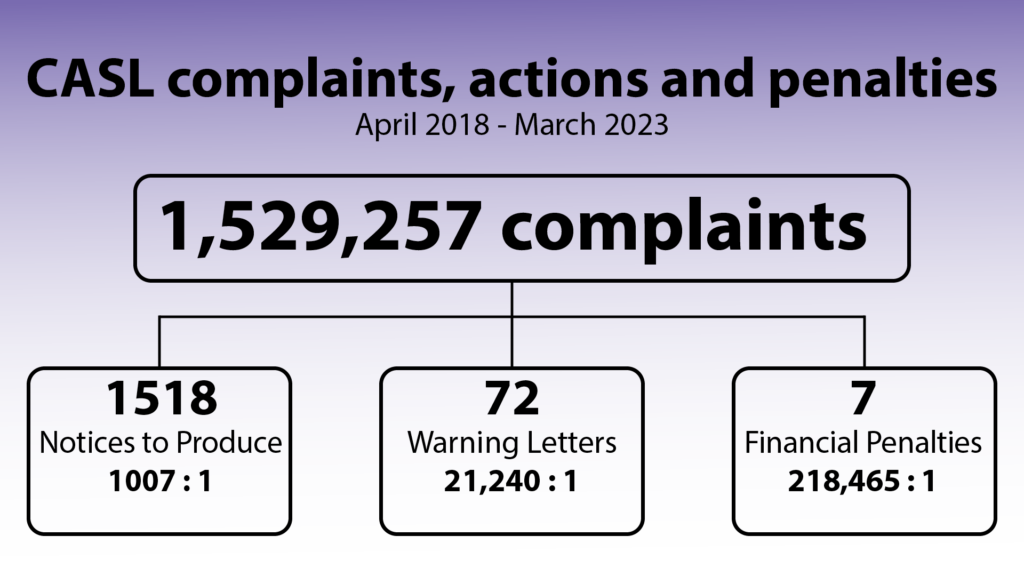

Low. Like, real low. The math remains 218,465 complaints per eventual financial penalty. The “lowest” threshold of effort CASL imposes, a notice to produce, still only happens once per 1000 complaints. That’s not a threshold, I’m not saying “nothing happens until you get to 1000 complaints,” that’s just how it averages out.

But, as detailed in the “Old Testament” section above, also horrifyingly arbitrary.

I am not a lawyer and this is not legal advice, but if I were to get one takeaway from all of this, it’s really a two-part maxim:

- Don’t be a jerk, and

- Do your best.

If I step back and squint and try to make sense of this decade of decisions, the pattern that seems to come through the fog is that getting CASL to focus on you is rare, and best-effort attempts to follow the rules seem to buy a lot of, if not absolute, forgiveness.

CASL decisions tend to land on unequivocal wrongs. There’s not a lot of stuff in the archives that suggests that they penalize innocent mistakes, or even grey-area decisions. There’s never been a decision that has come down on a public service organization, charity, or non-profit. Not to say there won’t ever be, but the focus seems to be on parties that are clearly doing wrong, should have known better, and did scammy, spammy things anyway.

Don’t break the law! Never break the law!

In principle, CASL is a good thing. It’s reasonably clear. We would all live in a better world if everyone followed these rules. So we should.

But… if you make an inadvertent mistake, or you look back at a campaign and say “oh, we should have done X,” or “I don’t know if we were in full compliance with Y,” I wouldn’t let it ruin your lunch. Learn, pull up your socks, and do better on the next one.

With text-based phishing and malware and online casinos and a whole planet of scammers, the top-of-mind analogy is the city’s on fire and there are riots in the streets. Jaywalking is still wrong, but if you forget to check the traffic lights at 2 a.m., you’re not the kind of problem the CRTC is looking for.

Wow, this went long

I didn’t mean for this to hit 3,000 words! I’ll stop here.

Next up, stepping a bit outside the review mandate, but bringing it back to my own interests: poking at whether or not students and academic institutions can be considered to be in a “business relationship,” which has a heavy impact on CASL but a lot of other things too. This might take a while. Expect more quick observations on IP, privacy and marketing in the interim while I chip away.

- 1The imposed penalties number does include a bit of my own math, as the 514-BILLETS case resulted in the issuing of $75,000 worth of rebates, which I calculated at far less than that value in terms of what the ultimate cost to the company would have been.