This is part eight of a multi-part series reviewing Canada’s Anti-Spam Legislation in practice since its introduction in 2014 and the beginnings of enforcement in 2015. Crosslinks will be added as new parts go up.

Part 1: Terminology

Part 4: Case File – Compu-Finder

Part 5: Case File Anthology, 2015-2016

Part 6: Case File – Blackstone Education

Part 7: Case File Anthology, 2017-2018

Part 8: Case File – Brian Conley/nCrowd

Part 9: Case File Anthology, 2019-2022

Core resources:

Enforcement Actions Table (CASL selected)

In April 2019, a $100,000 decision was imposed on Brian Conley (as an individual) for violations committed by the company he was CEO of, nCrowd, in a pair of identically dated decisions: first, a NOV, and second, a compliance and enforcement decision, both from April 23, 2019. You’ll recall this from our 2015-16 anthology post, where we saw the AMP issued (but not imposed) in December of 2016.1Confusingly, in the table of enforcement actions, the 2016 Brian Conley entry doesn’t link to the issued AMP, but directly to the 2019 decision, so we can’t see the issued notice, only the final decisions.

The introduction of vicarious liability

This is the first time vicarious liability has been named in a decision: “Background,” final paragraph:

As a result of the circumstances cited above, specifically the fact that the companies involved were operational then dissolved or otherwise ended, any enforcement actions directed towards such companies would have no deterrent effect nor effectively promote compliance. Therefore, Commission staff pursued the corporate directors through vicarious liability in order to encourage future compliance with the Act.

It’s also in the title of the NOV itself, “Notice of Violation: Investigation into non-compliant emails sent by Couch Commerce Inc. and nCrowd, Inc. including the vicarious liability of corporate directors.”

Vicarious liability is part of the Act, as is the responsibility of directors and officers, in [s31-32] of the Act:

Directors, officers, etc., of corporations

31 An officer, director, agent or mandatary of a corporation that commits a violation is liable for the violation if they directed, authorized, assented to, acquiesced in or participated in the commission of the violation, whether or not the corporation is proceeded against.2Note the “whether or not” here — in theory, although it hasn’t happened yet, the CRTC could double-dip with both an institution and an individual being liable. Also — this is past the limit of my understanding, but this only applying to “corporations” seems unnecessarily narrow, but there may be a legal definition of “corporation” that differs from my understanding of the word.

Vicarious liability

32 A person is liable for a violation that is committed by their employee acting within the scope of their employment or their agent or mandatary acting within the scope of their authority, whether or not the employee, agent or mandatary is identified or proceeded against.3See above note re. this allowing the CRTC to penalize individuals across management and labour tiers.

And if the name Couch Commerce seems familiar, it should – these Couch Commerce investigations resulted in an earlier NOV against Ghassan Halazon (“in his individual capacity”) in 2017, as covered in our 2017-2018 anthology. The CRTC states in its September 2019 Activity Summary that this is its first vicarious liability finding. Halazon was the first finding to be resolved, but remember that Conley was first issued the AMP in December of 2016, prior to Halazon being penalized.

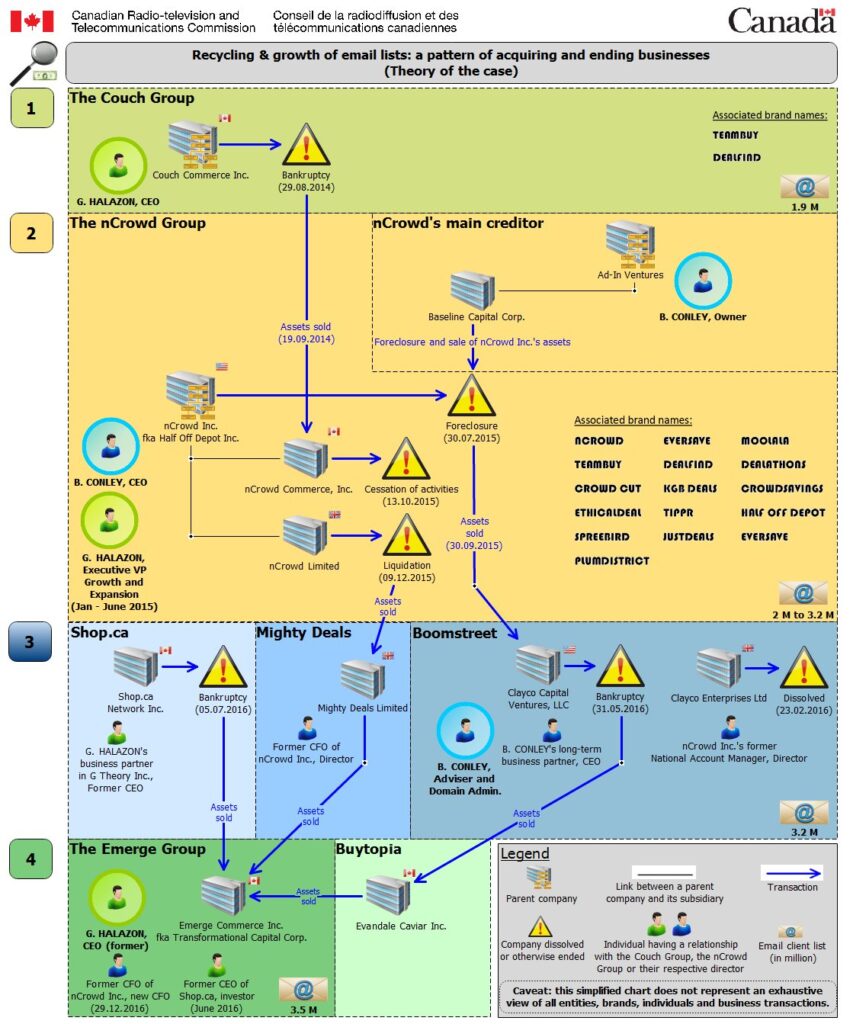

But nCrowd and Couch Commerce were only the tip of a massive, scammy iceberg: the web of companies connected to those two (and many, many brand names as well) was extensive, and kudos to whoever put the leg work in to pull it all together, resulting in this truly impressive chart that accompanies the NOV:

While the graphic design may be questionable, it’s quite a labyrinth of companies.

Where it lands is almost 3.5 million email addresses promoting what the CRTC doesn’t call, but I feel pretty free in describing, as a massive series of bait-and-switch deal scams; from the “Background” section of the NOV:

The key assets acquired in the chain of transactions listed in the chart were intangible, essentially the email distribution list, domain names and trademarks. These ownership changes allowed a new company to continue on the business with an ever larger email distribution list without the assumed liabilities of the former company. However, the continuity of service was damaged: as merchants ceased being paid for their products, they refused to ship products ordered by customers. As a result, both merchants and customers ended up losing money, since the voucher business closed or entered into bankruptcy proceedings before merchants and customers were fully compensated for their transactions.

Since these companies seem to launch and disappear rapidly (see the diagram above), the vicarious/director liability makes perfect sense. Tracking the person or people responsible, rather than the corporate entity, keeps the legislation viable when you’re dealing with MBAs who are shuttling through companies like three-card monte.

What’s not clear is how this is decided – why is Conley (and previously, Halazon) selected here, but in other instances, companies (Kellogg, Blackstone) are the recipients?

I have so many questions after seeing how Conley and Halazon, and nCrowd and Couch, are almost symbiotic through the life of these companies, their practically identical infractions, and the literally fractional penalty levied against Halazon as compared to Conley. Halazon was the executive vice-president of nCrowd while Conely was the CEO, for Pete’s sake.

In the Halazon NOV:

The investigation alleged that commercial electronic messages (CEMs) were sent or caused or permitted to be sent by Couch Commerce to recipients without a compliant unsubscribe mechanism during the period of 2 July 2014 to 9 September 2014, while Mr. Halazon was CEO of Couch Commerce. More specifically, it was alleged that the unsubscribe mechanism did not function, or could not be readily performed, or unsubscribe requests were not given effect until more than 10 business days after a request has been sent. It was also alleged that Mr. Halazon was personally liable for this violation pursuant to section 31 of the Act. 4Undertaking: Mr. Halazon and TCC; “Acts and omissions covered by the undertaking and provisions at issue,” para. 2

In the Conley NOV:

Commission staff alleged and the Commission found in Decision 2019-111 that between 25 September 2014 and 1 May 2015, nCrowd, Inc. sent CEMs or caused or permitted any of its subsidiaries, namely nCrowd Commerce, Inc. and nCrowd Limited, to send CEMs to electronic addresses, without consent and without a functioning unsubscribe mechanism contrary to paragraphs 6(1)(a) and 6(2)(c) of the Act.

Commission staff also alleged and the Commission found in Decision 2019-111 that Brian Conley acquiesced in these violations, while he was the President and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the nCrowd companies. As CEO, Brian Conley took no action and turned a blind eye to the practices being employed at his companies in terms of the acquisition and use of email distribution lists, despite the fact that in this line of business, an email distribution list is one of the most important assets through which to generate revenues. Protecting such an asset, including ensuring continued ability to use it, under CASL, should therefore have been important to the nCrowd group and its CEO. However, the nCrowd group’s email distribution and consent-tracking lists were largely inaccurate, incomplete, and altered.

- The type of consent is listed for each and every one of the 1,928,015 entries as “explicit” consent although a significant number of email addresses on this list were generic or belonged to institutions or governments, including police services and hospitals (some of which were available online).

- The date at which the consent was allegedly obtained and the legal person who allegedly sought and obtained the consent were obviously inaccurate or altered. For example, on numerous occasions consent was obtained for more than 3,000 addresses in just one day, and more than 80% of all parties provided consent (1,566,114) on the same day.

- nCrowd, Inc.’s non-compliant unsubscribe mechanism was a broad and recurring issue that Brian Conley ought to have known about over the time, and the appropriate steps to fix the unsubscribe process were never taken. The non-compliance continued for almost a year and evidence shows that even when the nCrowd group’s employees informed customers that they had been unsubscribed, they had actually not been.

- No evidence was found that Brian Conley ever verified or required the conducting of any audit of the consent list provided by the Couch Commerce group or other lists purchased by the nCrowd group to ensure its validity and accuracy.

- Brian Conley instituted no policies or procedures relating to the nCrowd group’s compliance with the Act.5Notice of Violation: Investigation into non-compliant emails sent by Couch Commerce Inc. and nCrowd, Inc. including the vicarious liability of corporate directors, “Investigation of nCrowd Inc. and its director Brian Conley,” paras. 1-3.

There’s clearly a gap there – Halazon/Couch doesn’t seem to have a problem with consent (or at least, consent goes unremarked on in the decision). Conley/nCrowd was clearly lying about consent, while having arguably identical unsubscribe issues. The email volume attributed to Couch Group (1.9M) and stated above for nCrowd (1.9M) seems to be the same.

Is this a $90,000 gap? The CRTC seems to think so.

This underscores one of the things I find unsettling about CASL: “The maximum penalty for a violation is $1,000,000 in the case of an individual, and $10,000,000 in the case of any other person.” [Act, s20(4)] But under that (to date never imposed) threshold, the purpose of the penalty is “to promote compliance with this Act and not to punish,” and factors for penalty are broad and very discretionary, and rely as much on comportment and ability to pay as they do on what is actually done in violation of the Act:

CASL, Purpose of Penalty, s20(2-3)

Purpose of penalty

(2) The purpose of a penalty is to promote compliance with this Act and not to punish.

Factors for penalty

(3) The following factors must be taken into account when determining the amount of a penalty:

(a) the purpose of the penalty;

(b) the nature and scope of the violation;

(c) the person’s history with respect to any previous violation under this Act, any previous conduct that is reviewable under section 74.011 of the Competition Act and any previous contravention of section 5 of the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act that relates to a collection or use described in subsection 7.1(2) or (3) of that Act;

(d) the person’s history with respect to any previous undertaking entered into under subsection 21(1) and any previous consent agreement signed under subsection 74.12(1) of the Competition Act that relates to acts or omissions that constitute conduct that is reviewable under section 74.011 of that Act;

(e) any financial benefit that the person obtained from the commission of the violation;

(f) the person’s ability to pay the penalty;

(g) whether the person has voluntarily paid compensation to a person affected by the violation;

(h) the factors established by the regulations; and

(i) any other relevant factor.

Philosophically, I understand this. But in practice, this results in published decisions that have such big swings, with no share information as to why, that it makes the entire scheme seem very arbitrary in its application and enforcement.

Which may be a feature and not a bug – I’ll address that in my wrap-up.

Issued penalty: $100,000

Final penalty: $100,000

Total issued AMPs: $2,667,000

Total imposed AMPs/monetary penalties: $953,250

Differential: $ 1,713,750

Up next: the 2019-2022 anthology. Technically there’s only one 2019 decision after Conley, and it’s only the issuing and not imposition of an AMP, so this will be a smidge broader than the previous anthologies.

- 1Confusingly, in the table of enforcement actions, the 2016 Brian Conley entry doesn’t link to the issued AMP, but directly to the 2019 decision, so we can’t see the issued notice, only the final decisions.

- 2Note the “whether or not” here — in theory, although it hasn’t happened yet, the CRTC could double-dip with both an institution and an individual being liable. Also — this is past the limit of my understanding, but this only applying to “corporations” seems unnecessarily narrow, but there may be a legal definition of “corporation” that differs from my understanding of the word.

- 3See above note re. this allowing the CRTC to penalize individuals across management and labour tiers.

- 4Undertaking: Mr. Halazon and TCC; “Acts and omissions covered by the undertaking and provisions at issue,” para. 2

- 5Notice of Violation: Investigation into non-compliant emails sent by Couch Commerce Inc. and nCrowd, Inc. including the vicarious liability of corporate directors, “Investigation of nCrowd Inc. and its director Brian Conley,” paras. 1-3.