Especially the writers.

In a role where I’m part director and part do-er, I keep a very active hand in everything from composing Tweets to writing five-year plans. I came up through the business as a mutt, with everything from community radio to professional journalism to strategic marketing under my belt.

But among all the past experiences, I think comics writing has been the most valuable.

It was never my job, in the sense that it was paying me a full-time salary. At the best, I got pizza money; for the vast majority of my work, nothing but the joy of doing it. There was one time where a creator-owned series I did got optioned and was being pitched around for a prestige TV adaption, but that’s a story for another time.

I’m slowly picking up old comics project and adding them to the blog; it’s a bittersweet experience, to be honest. So many great ideas and passion that never quite made it over the hump to being well recognized or self-sustaining.

But the joy was in the doing, as my friend Adam reminded me recently.

It was also in the learning!

I legitimately believe that every creative person should try comics, for a while, at least once. Not just one page, and not just writing, but the whole process. I’ve been a writer for 99% of the comics I’ve done, but have tried my hand at full process at things like 24 hour comics jams. I was a very good artist when I was in the third grade, peaked in the fifth grade, and think I can now draw about as well as most fifth-graders. It doesn’t stop me from making comics, and it shouldn’t stop you either.

At the moment, though, let’s talk about marketing, writing, and writing for comics.

What does writing for comics teach you?

Economy of language

This is tops. Especially in some formats of comics. I’m in the process of moving a decade of a daily strip I did with my good friend and brilliant art madman James Duncan to the blog. It was a M-F four-panel comedy strip that was also a serial story, about a man who was bitten by a radioactive man and gained the proportionate abilities of a man. It was called Man-Man.

Here’s the thing about a four-panel daily strip: it has to be punchy. You have four panels a day to tell a story. Given panel size constraints, you really shouldn’t have more than two people on a panel, sometimes three. You shouldn’t have more than 10 words in a word balloon.

So — while it never paid in money — writing a long-form serial adventure, that unfolded in four panels a day, where there were never more than two people speaking at once, and only speaking in bursts of 10 words or less — it paid in experience.

I am a wordy SOB, and this was hard. Bleed-from-the-eyes hard. It was not, admittedly, super funny sometimes (that’s on me, not James). But expressing what needs to be expressed — and striving to end in a joke every day — taught me in immeasurable amount about compact writing.

Image/text meshes

Never tell what’s showing, is essentially the golden rule. If a character is pulling a gun, having them say “I’m pulling a gun!” is pointless. If the artist has invested the on-panel action in the gun-pulling, he’s freed you up to have that character say something else entirely. It can be prosaic and additive (“I’ve been waiting five years for this, Tompkins!”), or show disassociation (“Nice day for a picnic, isn’t it?”) or even lunacy (“The banana people live under the stairs!”).

Point being, getting a handle on how text should complement image, and not be redundant to it, is critically important. Text can even contradict an image, for some sort of jarring narrative effect, but it’s another form of economy that comics teaches you real fast.

The passage of time, and scenes

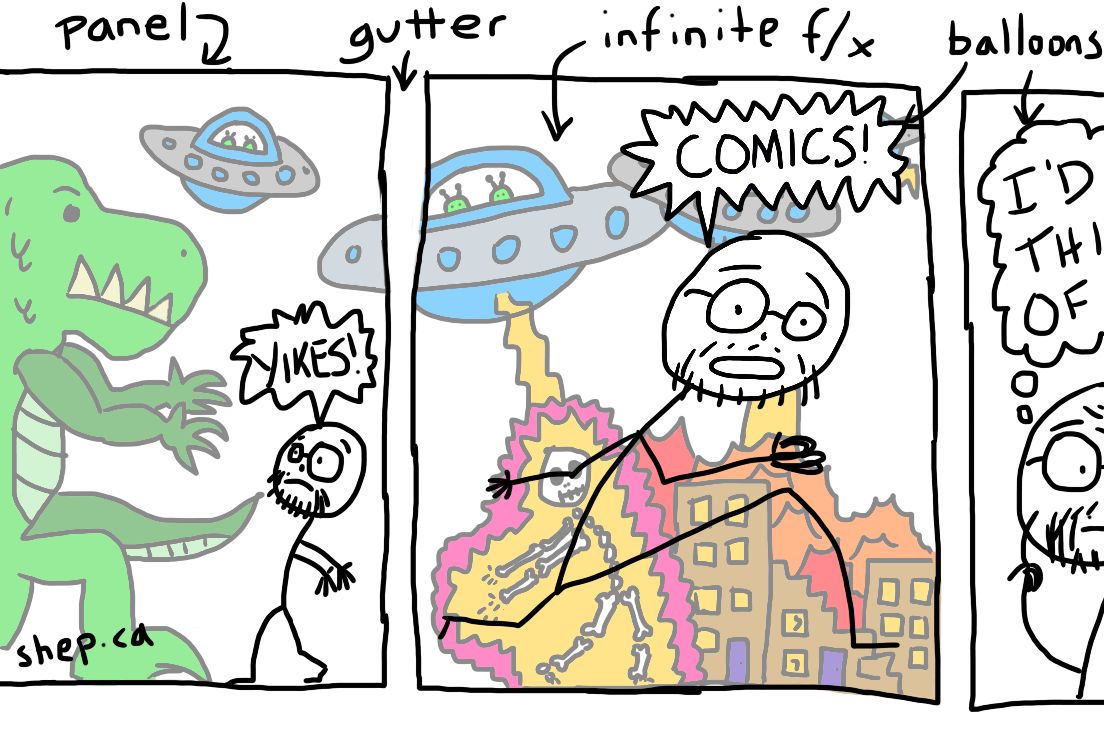

Scott McCloud, certified genius and comics-maker, talks about this a lot in his book Understanding Comics, which I’d argue should be in every creative’s library. The space between comic panels (“gutters”) contain fungible amounts of time and movement, and every unit of comic (panels) can leap through time at the speed the author desires. I’m mildly mangling the word “fungible” here because it’s kind of an exchangeable commodity, in that you can choose to have the gutter or larger panels, and the division depends on how you want the passage of time, or a split in locations, to be perceived in the narrative — going full comics nerd at this point, sorry.

It’s a low-cost, intensive way to really understand how time works in narratives, and a great way to cut your teeth for future video production. Will your next shot be the next moment in a sequence, or five years later? Will your next shot stay in the same place, or take you to a new location?

Narratives

I call everything I do “storytelling” in internal conversations, which I’m sure makes some of my colleagues think I’m a pretentious weirdo sometimes. But they are! Every social media post is a story. Every news item is a story. Every research profile is a story.

Comics make you tell stories while thinking on that image/text mesh plane. Above and beyond that mesh, you’re also thinking of beginnings, middles, and ends. This isn’t exclusive to comics, but it separates the good’uns from the bad’uns: what’s your act structure? What are your impact points? What do you need a full-page splash for, versus a tiny inset panel?

Tell a story in 24 pages of nine-panel grids. Then tell a story in a single page with 12 small boxes of art and words. Then tell a story in a four-panel comic strip. Then in one big image/text combo.

Once you can get ideas down in a single panel that have a beginning, middle and end, and marry compelling art with prosaic text, you’re ready to write a tweet. Or film a killer Tik-Tok minute. Or even write a 3,000-word feature, but mindful of what pictures you’ll need at the other end to make it sing.

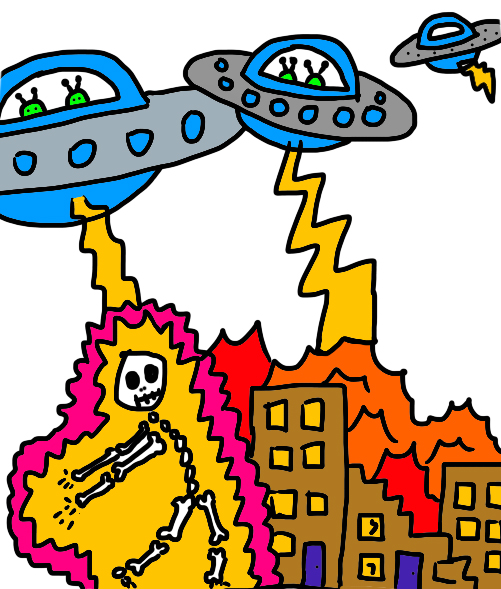

Infinite budget

The project that broke me was a crazily ambitious series called Rise, Kraken! that at one point had a group of agents for an international crime organization called Kraken trapped in a facility with killer panda bears that spoke through Speak-n’-Spells grafted to their chests, being pursued by an army of hundreds of howler monkeys. At another point, zeppelins were being taken out by weaponized War Tubas. I haven’t put it up on the site yet because I need to find the art (and ask the artist for permission to post it). I wrote an adaptation of Captain Blood, the classic novel of piracy, with full-on multi-ship naval battles raging throughout the narrative.

More than any other medium, comics let you think big. As much as they force economy in the word balloons, there’s an infinite canvas of ideas and space you can draw on. There is no better training ground for the imagination.

Tremendous constraint

The infinite budget is trapped within a confined physical space. Usually something about as big as a letter-sized piece of paper. Sometimes just a comic strip. Sometimes a two-page spread. Your omnipotent powers are trapped in a box of a certain size, and you have to deploy all of the above skills — mastery of the economy of language, the word/text mesh, the passage of time and space — to have the infinite idea translate into a very finite space.

Learning to work with artists

Comics artists are not in it for the money. It’s a notoriously difficult profession to break into and stick with. Also true for writers, but while a writer can write a comic in a few working days, it takes an artist at least weeks to draw one. So the investment ration in the writer:artist relationship is way out of whack.

Since writers are also conventionally the “idea people,” it’s frankly a weird dynamic. Sometimes you luck out and find an artist who is completely in sync, and totally committed to the bit, and you take it as far as it goes.

Often, though, the artist — stops. They’ve found a better-paying gig (or a paying gig, period), or they’ve lost interest, or there isn’t a payoff to the project that seems evident and they want to focus on other things. Unless you’ve got a lot of money to pay them to follow through on things (I didn’t), you can’t really fault them. You can cajole, wheedle, promise, negotiate — but you’re ultimately powerless in the hands of another to see something get to fruition.

It gives you a ton of hands-on experience in sharing an idea, inspiring somebody to get on board with it, and then being as consistent and reliable as humanly possible on your end to ensure they get what they need to succeed. Some artists need things explained in complete detail. Others much prefer “I need a fight scene here, and it has to end like this.” You learn to work with all sorts of other creatives, from the affable to the temperamental.

[This is a bit of a demarcation line -- from here it’s less “what can you learn from working on comics for a bit” to a more diarist “what did I learn from a decade-plus of beating my head against a wall”. You can skip down to the end if you want to avoid the maudlin bits.]

Learning to pitch

This is getting a little far afield of what anyone can learn by doing comics for a while. But part of the process when I was trying to make a go of it was pitching comics companies, large and small, to see if they’d be interested in what you were doing. In retrospect, I think all of this would have been much easier if I’d been in a place where I could form relationships, instead of in Sherbrooke, Quebec for the bulk of this part of my life.

It was, again, a tremendous skill to learn. How do you package something to get somebody’s attention? What do publishers need to know vs what audiences need to know? How do you sell something with a 2-3 sentence email that entices somebody to take the time to open and read the attachment? It’s its own art, and concurrent with working as a copywriter, then strategist with a national ad agency, it was a good art to learn.

Learning to fail

You may have noticed I’m not a professional comics writer. Which is fine — with time and some tempering, I can even admit to myself now that if I’d been given the opportunity to pursue it, I’d be a solidly b-list writer: probably pretty good, with solid ideas and sound writing, but not up there with the Alan Moores and Grant Morrisons, Dwayne McDuffies, Kelly Sue DeConnicks, Tom Kings, etc. I would have been fine. I would not have been great.

Through one lens, my comics-writing “career” was a succession of failures — good ideas that never found an audience, drawing-board projects that never found a publisher, amazing ideas that never found the right artist to even push through the pitch phase.

The “coulda, woulda, shoulda” has been painful at times. Even loading old projects onto the blog (and I’m not even 10% there — I did a lot over almost two decades of striving) is bittersweet. No fewer than four of my former collaborators have their own Wikipedia pages now, which feels weird. My wife had to see me through a legitimate identity crisis about five years ago, when we went to a comics convention in Toronto and I ran into a few collaborators who were cutting their teeth at the same time as me and are now thriving in the industry.

For a very long time, though, I would get myself up, dust myself off, find as much passion for one project as I had for the last, and plunge back in. The “final” project was one I truly believed would set the world on fire, crashed and burned when the artist involved just decided to stop working on it with no further explanation, and that… capsized me. That was the hard stop — I haven’t written for comics in the decade-plus since.

Not the passion, though — that just started to go in other directions. Creativity at work, other personal projects — even, eventually, this thing right here. There’s no shortage of outlets for the creative spark if you’ve got it and want to invest it somewhere.

But I learned a ton from not succeeding. Every non-success was its own learning process, and contributed to all of the above — economy of language, an understanding of the mesh of art and language, developing a relationship with the passage of time and space. It also built scar tissue, and the ability to put disappointment behind you and move on to the next thing. There’s always a next thing.

In short, make comics

It doesn’t have to be a big thing. But you can do it today! Now! Grab a sheet of paper, draw some boxes, and have Stick Person 1 go on a little adventure. Think about the infinite possibilities inherent in that blank page, but also the tremendous constraints of that physical space. Hell, just take a bunch of panels from an existing comic and draw over the word balloons. But get in there and experiment. See how the words mix with the images and complement (or contrast) them.

I guarantee you won’t regret it.

April 25, 2021

Soundtrack:

Jason Collett, “Best Of“

AceMoMa, “A New Dawn“

Lo Talker, “A Comedy of Errors”