I’m testing modern footnotes 1Hello modern footnotes. Where will it appear? What will it look like?

- 1Hello modern footnotes

I’m testing modern footnotes 1Hello modern footnotes. Where will it appear? What will it look like?

My wife and I try to attend the Union Gallery’s annual fundraiser every year. It’s called Cézanne’s Closet; the format is you pay $100 for a ticket, and about 100 artists donate work to the gallery. You browse before the event, and then ticket numbers get called at random. If your number comes up, you pick a piece of art to keep!

It’s a ton of fun, especially as a couple — there’s always an interesting evaluation-and-negotiation phase to hit on pieces we both love.

This year, though, our #1 was identical when we compared notes: Wrong Turn at Point Pleasant, West Virginia, by artist Darby Huk.

We were chuffed! Darby’s a Master’s student at Queen’s University, and we could hear her on the Zoom call for the gallery event, so I knew she was in town.

Unbeknownst to Marisa, I reached out to her after the event and asked if she’d be interested in a commission of two more paintings to make it a trio of sorts (I don’t think this is technically a triptych, but I’m calling it that anyway), keeping with the “cryptids and vices” theme. Fortunately, she was into it! So we bought two more paintings from her…

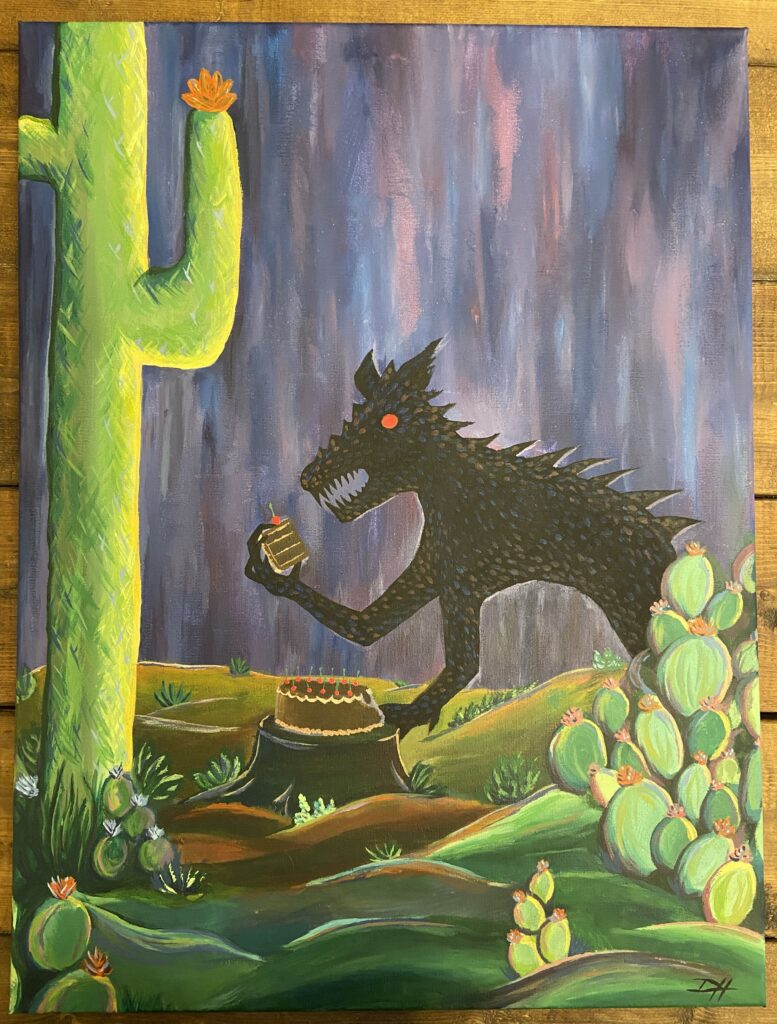

¡Cumpleaños! Puerto Rico

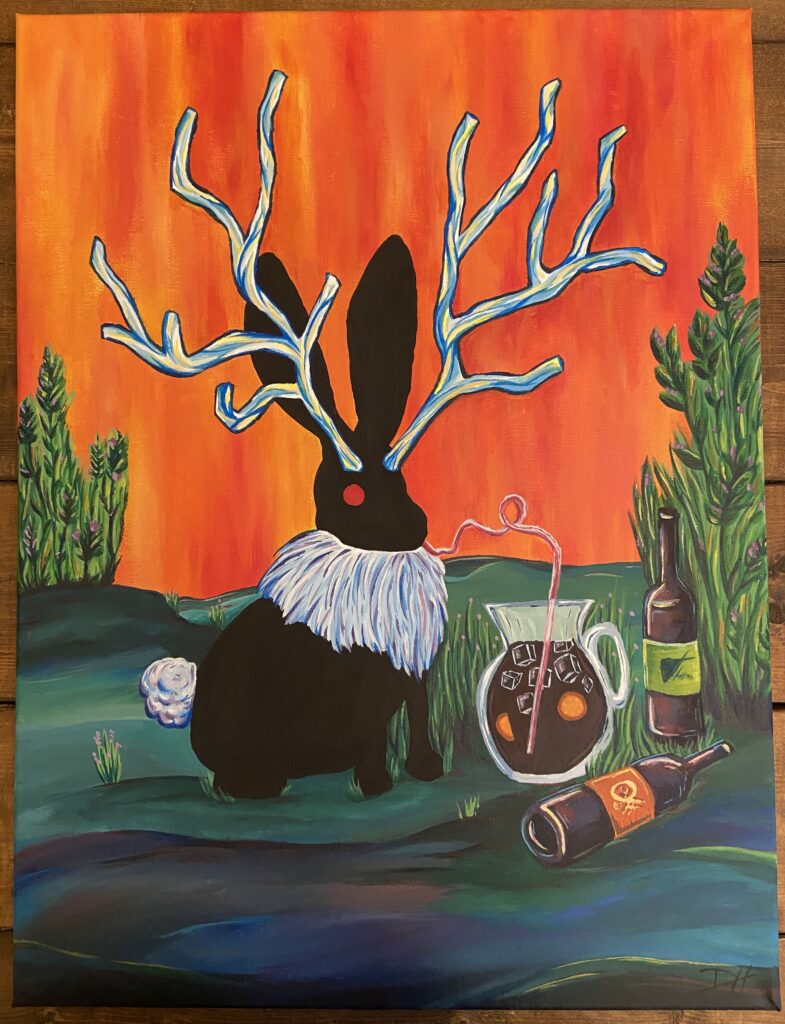

Girls Night, Douglas, Wyoming

Together, they look like this…

Again, we’re super stoked! Now we just have to figure out where we can clear some wall space…

Yesterday at around 5:30 in the evening, a great light went out in the universe and a great part of my heart died.

After a terrifying incident and bounce-back two years ago, Pooper started fading again five or six days ago, and… there was a long paragraph here about the circumstances of her passing, but I cut it out. It’s not important. It’s how the story ends, but it’s far from the important or best part of that story. It’s enough to say that she gave me kisses and snuggled in hard as she passed, and let out a familiar little sigh and was gone. I spent some time with her after, and Marisa and I went home on a cold night with the threat of snow in the air.

I could write a book about Poopercat.

Not like a children’s book; a 900-page epic. Full bore Tolstoy. It’s hard to describe her to people who didn’t know her; she was a boundlessly positive presence, open and trusting and loving and curious.

The beginning of the story is when Marisa and I went to the Societé de Protection des Animaux in Sherbrooke over a decade ago. Marisa wanted to find a dim boy cat because her beloved Ozzy had died several months before. We looked at all the cats in cages but none of them vibed. Then we went to the play room, and out of all the cats in the back of the room, a tiny calico with bright eyes bounded over to us. When I reached down to pet her she hopped up on my shoulder and nuzzled my ear, and when Marisa bent down to pat her she gave Marisa kisses as well. We hadn’t thought of a girl cat, but as we left we realized she was the one. When we returned two days later, she was gone, and we were terribly sad — until from the back of the play room a pair of ears and eyes emerged from a hammock, and then she bounded down and ran over to us like she’d been waiting anxiously to come take her home.

We took her home.

She was so scared when we let her out of her cage that she hid under the steps to the basement; I got a blanket and a book and sat there and read Don Quixote for over two hours until she eventually came out.

And then she was My Cat. We signed some sort of contract in that moment where we would be best friends forever. And we will be best friends forever.

I’ve had other cats, and my family had dogs as a kid, but Moxie Parker was my first experience with pure unconditional love. She’d follow me around the house, squeak to be picked up and patted, and spend every moment she could with me. She thought I hung the moon and the stars, and I tried to meet that with my dumb imperfect human love as well as I could.

She made me a better person. Being the recipient of such pure and unconditional affection made me a warmer, more affectionate person. Her simple focus on simple joys — a good nap, a good meal, a sunbeam, and loving and being loved in return — helped ground me in what’s important and appreciate the joys of daily life and deal with some of its frustrations. She changed me, forever, for the better, and Marisa, too.

It’s hard to describe her personality, really. “Affectionate” is covered above, but also this undefinable combination of intelligence, curiosity, and enthusiasm for things.

She had a quality where you just wanted to make up and tell stories with her.

And we did. Over the course of over a decade, Marisa and I made up countless personae for Moxie Parker. The very first, I’d venture, was Moxie Parker, Girl Detective, when she’d bumble around the house and poke at nooks and crannies and explore. But the list grew, and grew, and grew, and her sweet silliness gave rise to our sweet silliness, and we were all sweet and silly together. Here’s the list, which we compiled several months ago. Much of it is incomprehensible to the casual viewer, because these were in-jokes that only three people in the world knew about and understood; two humans and one cat (or several dozen cats):

Every one of those comes with stories. Every one of those could take an hour to explain. And there’s so much more.

I gave her “pony rides” when she was a kitten through a cat; I’m sure it happened in Kingston, but the clearest memories are Sherbrooke: I’d get on my hands and knees and she’d hop on my back, settle into a comfortable position (often facing backwards, for some reason) and I’d crawl around the house with her riding on my back like a princess, usually dropping her off at the bed in the bedroom, where she’d gracefully alight and then lie down for a nap. This sounds really stupid when I write it down, but I got a huge kick out of it, and so did she.

Her absolute passion for the Big Room, which is what we called the side deck and yard. One click of the door lock and she’d launch herself from her saucer bed in the kitchen and hustle to the door, practically knocking you out of the way to get out, where she would walk on the garden stones to avoid touching grass (lava!) and would loll in the sun, so happy that she’d just roll slightly back and forth on her back and squeak in the warm sunlight. When winter hit, the first time you’d open that door and the cold would hit her nose and she’d recoil, shaking her head quickly, looking at you like you broke it. But every spring, the sheer joy of going back out again.

Her excessive caution coming down stairs, leading with front paws and then both back legs with a deliberate hop, and — if you somehow got downstairs before she did for breakfast — listening to that unique hop, but faster than you thought possible.

Her tremendous fondness for boys, especially big guys with beards — she could walk into a room full of people and would beeline for the burliest man with facial hair.

Sleeping with us — me — almost every night, starting out standing on my chest and getting pats, then settling in between or behind my knees for the night. Always coming upstairs for naps, usually lying beside me, where she’d snuggle in between my torso and my arm, rest her head on my arm, and give a little sigh before falling asleep. As she was getting older, I made a box to help her hop up on the high bed in the bedroom; it had a little wobble to it, so every night I would lie there, waiting to hear her soft tread, then the wobble of the box, then her ears and eyes peeping over the side of the mattress, before she hopped up for a cuddle and some sleep.

COVID couch cuddle time: once I transitioned to working from home, it became a lunchtime ritual that I’d lie down on the living room couch; she’d clamber up, climb on my chest, practice some face-merging, then snuggle in so that she was nestled on me and against the back of the couch, wiggling into position and then letting out a sigh — that little sigh! — of contentment before falling asleep. Sometimes I’d doze too, sometimes just lie there for a while. If she didn’t get her couch time at lunch, she’d get angry, and barge into my office in the early afternoon and squeak until she got pats.

Her love/hate relationship with Digby, who she called the Goblin — sometimes playing with him, sometimes chasing him around the house in a state. He’s a skittish cat, which would trigger her to get at him, and if there was a loud noise anywhere in the house, she’d get up from her saucer or bed and go looking for him, looking all the world like she was rolling up her sleeves, to see if he was vulnerable and ripe for a chasing.

Her distinctive, swaybacked, “skatey-legged” walk, gliding rather than stepping, a kind of side-to-side motion with her low center of gravity and determined gait.

Her morning routine of having Marisa pick her up on a kitchen stool, holding her like a baby, with Marisa trying to steal kisses and Pooper putting up the “no paw” to keep Marisa’s face away from her face.

The way she could make me happy just by walking into the room. The way she _lit up_ a room.

She permeates every room of this big old house. There isn’t a couch or a chair or a vent where I don’t expect to see her snuggled up in having a nap, or a stairway or a hallway she shouldn’t be hopping down or skating along. Last night was largely sleepless; I can’t lie in our bed without the absence of her weight and warmth next to me turning into a terrible abyss. Every room I enter I catch my breath because I’m hoping to see her.

Somewhere up in that list of things is “Unto every generation, a Poopercat is born!”, which started as some sort of dumb Buffyesque riff on the idea that a cat of her spirit is gifted to every generation, and — like the Buddha — if one Poopercat passes, another great spirit rises somewhere else. And, in between fits of doing things I thought only happened in books and movies (crying so hard you pull a muscle behind your eyes; literally collapsing in tears; making sounds you’ve only ever heard in horror movies featuring mutant woodland animals), this is an idea that gives me profound comfort.

Two years ago, when she was very very sick, I made a cot and slept next to her in her saucer bed on the kitchen floor, by the warm vent, for three nights. She was too ill to move. I laid there and gave her pats and wept and asked her, and the universe, for please, just a bit more time. Just a bit more time basking in the warmth of her. And I got it; she recovered, miraculously, and there was two more years of kisses and fun.

So I can’t complain. Not really. I got a full complement of Poopercat, and then I got two extra years. That’s a triumph.

And now, unto a new generation, somewhere on this big dumb planet, somebody who really needs a Poopercat will find one.

Somewhere on earth, somebody is meeting a cat for the first time, and the cat is saying “I’ll be your best friend forever if you’ll be my best friend forever.” Maybe it’s in India, or Spain, or Iraq, or the Russian Steppes. Somewhere, a cat and her person are meeting for the first time, and making a deal: it can’t last forever, but for as long as it does, there will be a bond of unconditional love and trust and friendship. Somebody will know what unconditional love feels like, and will grow and become better and stronger for it.

That’s the one thing that makes it okay right now: the idea that somebody is finding their Poopercat today, and making the deal that I made. It ends with heartbreak, but the joy on the journey far outweighs the pain at the end.

There will be cuddles and silliness and lolling in sunbeams and time on the couch and snacks and careful hops down the stairs and stories and laughter.

And love, and love, and love.