Apartment Fancy

Charitable Air

Stairs to Nowhere

Artillery

Apartment Fancy

Charitable Air

Stairs to Nowhere

Artillery

Walking down around Cataraqui Street and up River Street, I came upon an overlowing dumpster next to a clearing in the woods.

Behind it, a cleared-out homeless camp. I don’t know if this was a police/city action, or what. But it was vast. I initially stuck my head in, then took a few steps in, then kept going, and going. I must have walked 250m into a long chain of connected clearings, beat down by human traffic, before I backed out. Largely because I was being devoured by mosquitoes. I don’t know how far back it went. There was lots of expected detritus — tarp, mattresses — but also a car bumper and other stuff.

Coming back out, the dumpster again. Tents, tarps, clothes, construction supplies.

Just past the dumpster, written along the sidewalk, a poem by Mary Oliver:

(forgive my anti-steadicam lurching gait!)

Where are all these people now? It can’t have been easy back there, in the heat, the humidity — as mentioned, I was being gangstalked by a horde of mosquitoes after about 30 seconds. It surely can’t be easier wherever they are now, without whatever community was back there in the sprawl of clearings, tents, and tarps.

There are a zillion studies that show that homeless people are not all drug users or petty criminals, but that default stereotype drives a lot of resentment — even hate. Hell, I’ve had trespassers steal things out of my back yard, off my laundry line; my garage has holes in the door where somebody tried to pry it open. I’ve been furious about “them” making me feel unsafe or inconveniencing me.

This really unsettled me in its scope. It’s easy to see a tent in a park or a couple of tents by the roadside and think you’ve seen “the problem”. The depth of this, the extent, really hit home for me. This was an entire village, out of sight, now wiped out and scattered and thrown in a dumpster.

Here’s that Mary Oliver poem, for those who don’t want to watch me read it poorly:

Of the Empire

© 2008 by Mary Oliver

We will be known as a culture that feared death and adored power, that tried to vanquish insecurity for the few and cared little for the penury of the many. We will be known as a culture that taught and rewarded the amassing of things, that spoke little if at all about the quality of life for people (other people), for dogs, for rivers. All the world, in our eyes, they will say, was a commodity. And they will say that this structure was held together politically, which it was, and they will say also that our politics was no more than an apparatus to accommodate the feelings of the heart, and that the heart, in those days, was small, and hard, and full of meanness.

From her 2008 collection, Red Bird, p. 46

Published by Beacon Press 2008

Yeah. That.

Murals from the barn at the nearby Memorial Centre. Clearly somebody has had a little fun with black spray paint.

From an earlier walk, my new friend Wilbur Potatoes.

Artsy House (New Mexico Vibes)

Morning Mart (also retroactively adding to my Convenience Store round-up)

Pretty Window. I tried to angle this to not invade the privacy of the sweet l’il old lady who lives here. Any day that the weather is nice and it’s not raining, she’s out on the sidewalk on a folding lawn chair in a dress and a pink hat, saying hello to anyone who walks past.

Pizza Monster (best pizza in Kingston, hands down) and its side mural.

Blaney’s Florists, owned by the Blaney family.

Forty feet away, Kevin J. Blaney, Florist. I suspect Succession-type drama!

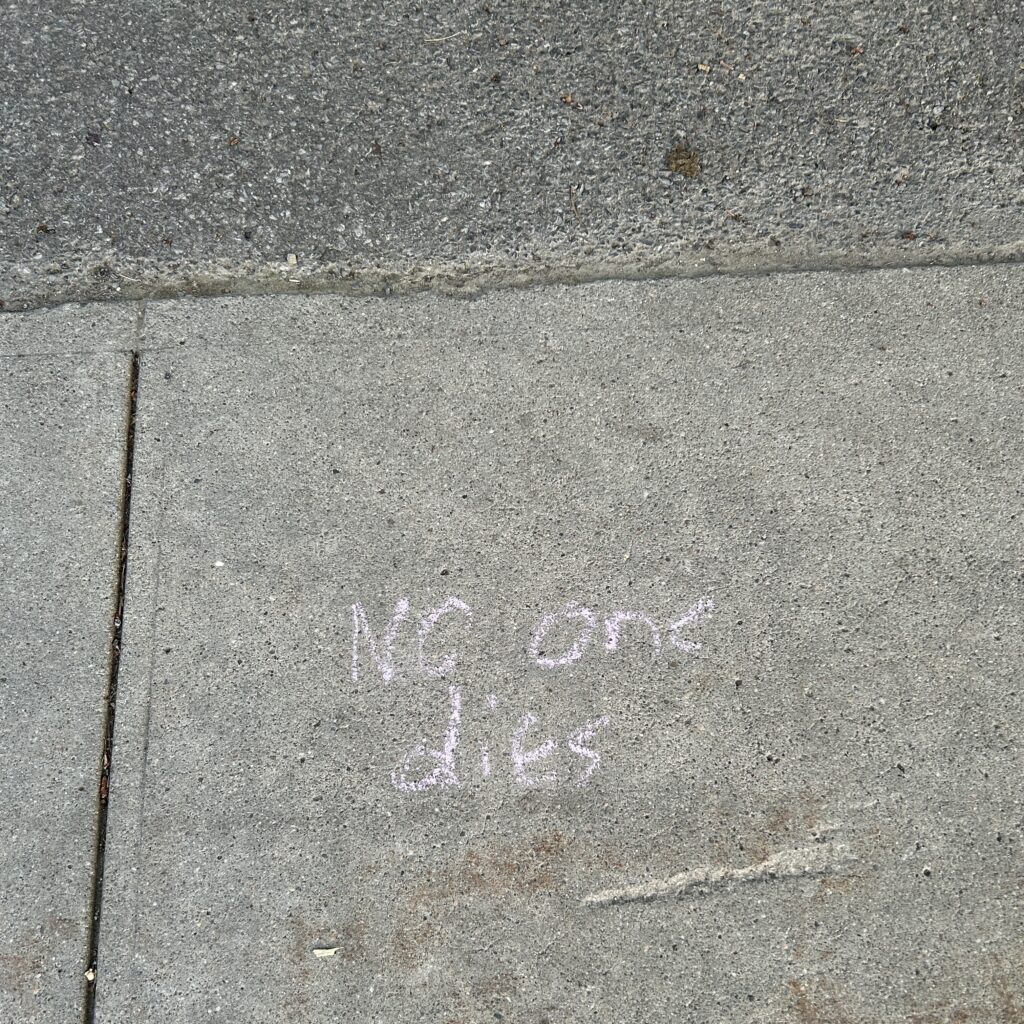

no one dies

Maple Stump

Fancy Door

Imperious Window Kitty

Portal Window

Frontenac Express. It’s not clear in the photo, but it stands maybe 3′ tall — a smidge taller than kitchen-counter height. I’m baffled.

Marie Antoinette Flower Shop (again)

Flower Cones

Window Display.

Typhus Memorial. “What’s typhus?” Don’t worry, kids, we’ll be seeing a lot of it in Texas, and Alberta, Canada’s Texas, soon enough.

Pizza boxes

Cloth cross

Apartment Building, Concession St.

Sidewalk Café

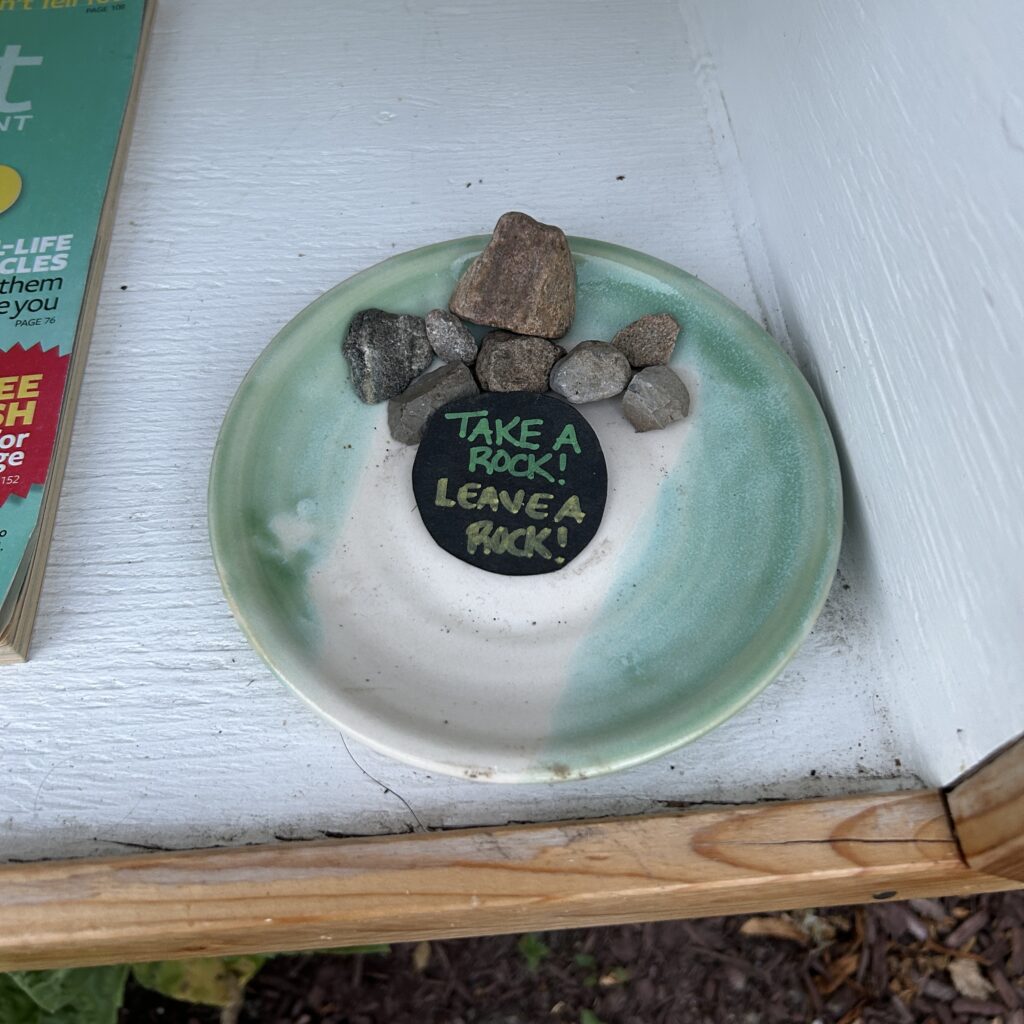

My New Friend Rocks McGuffin

The Hoagie House (A Meal In Itself)

Soft Focus Window Kitty

Porch Akimbo

Fresh Cuts

Maison Paul

Utility Box O’ Lantern

Urban Buns

Orange sunflowers

Freshly Paved

Lopsided Doors

Take A Rock! Leave A Rock!

Porch Skeleton

Kids, Gump-Gump Lives In The Yard Now

Home Business

Eckin — Echinea — Enchi — Round Goddamn Ball Flower

Hey, man, sometimes you just want to take pictures of flowers.

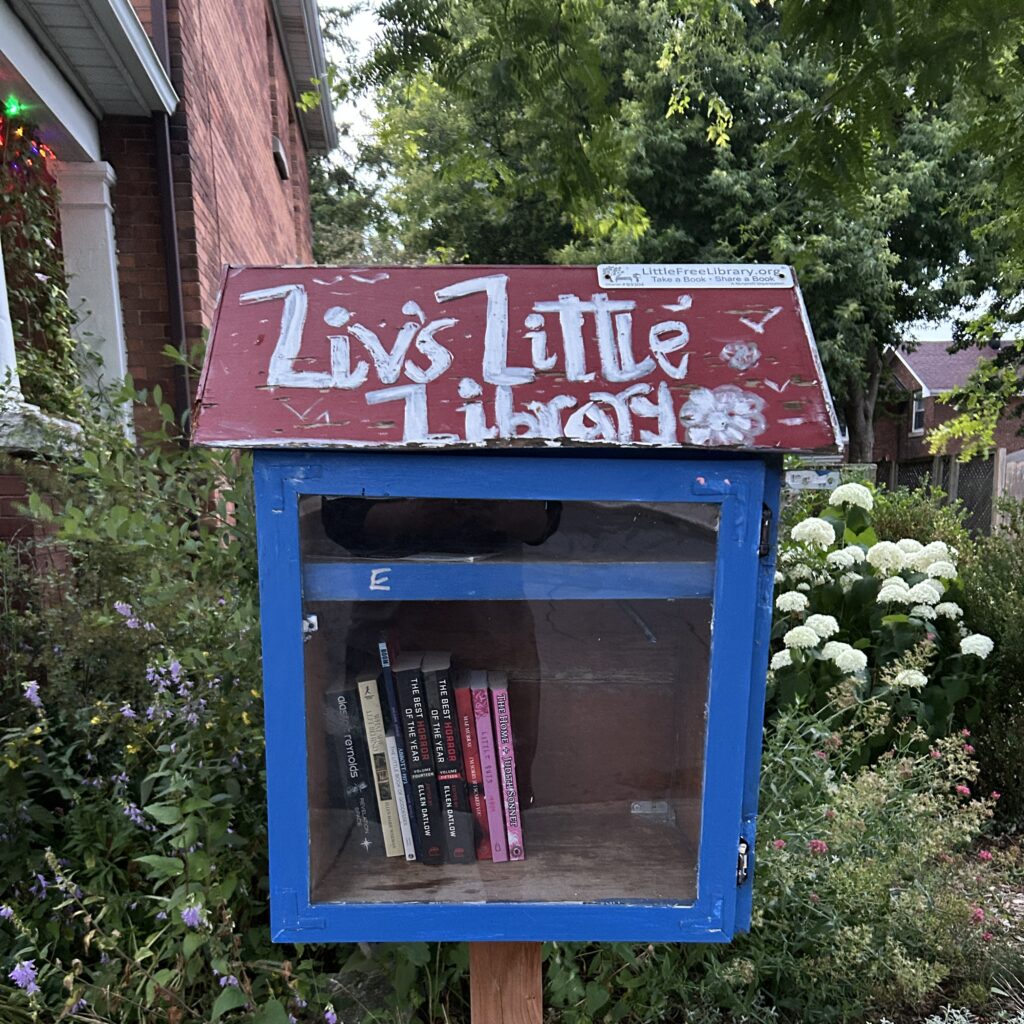

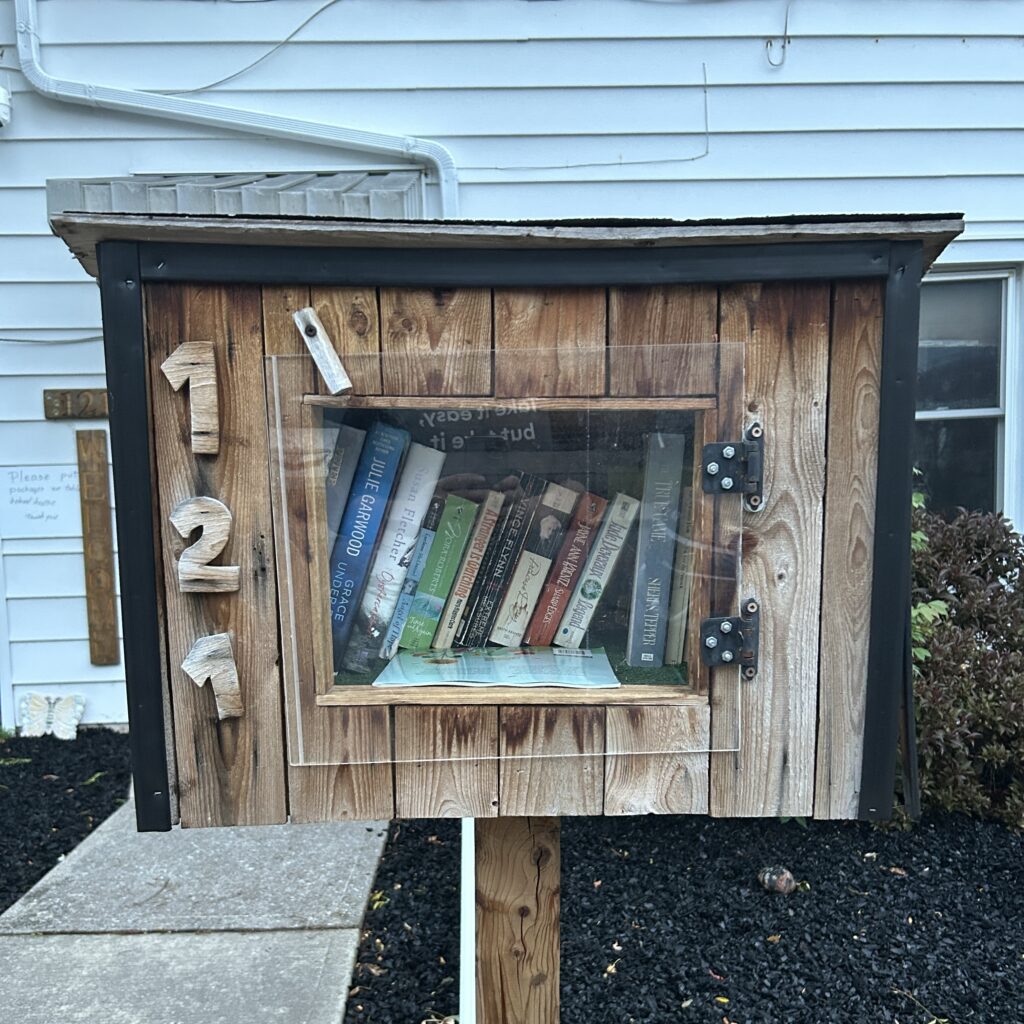

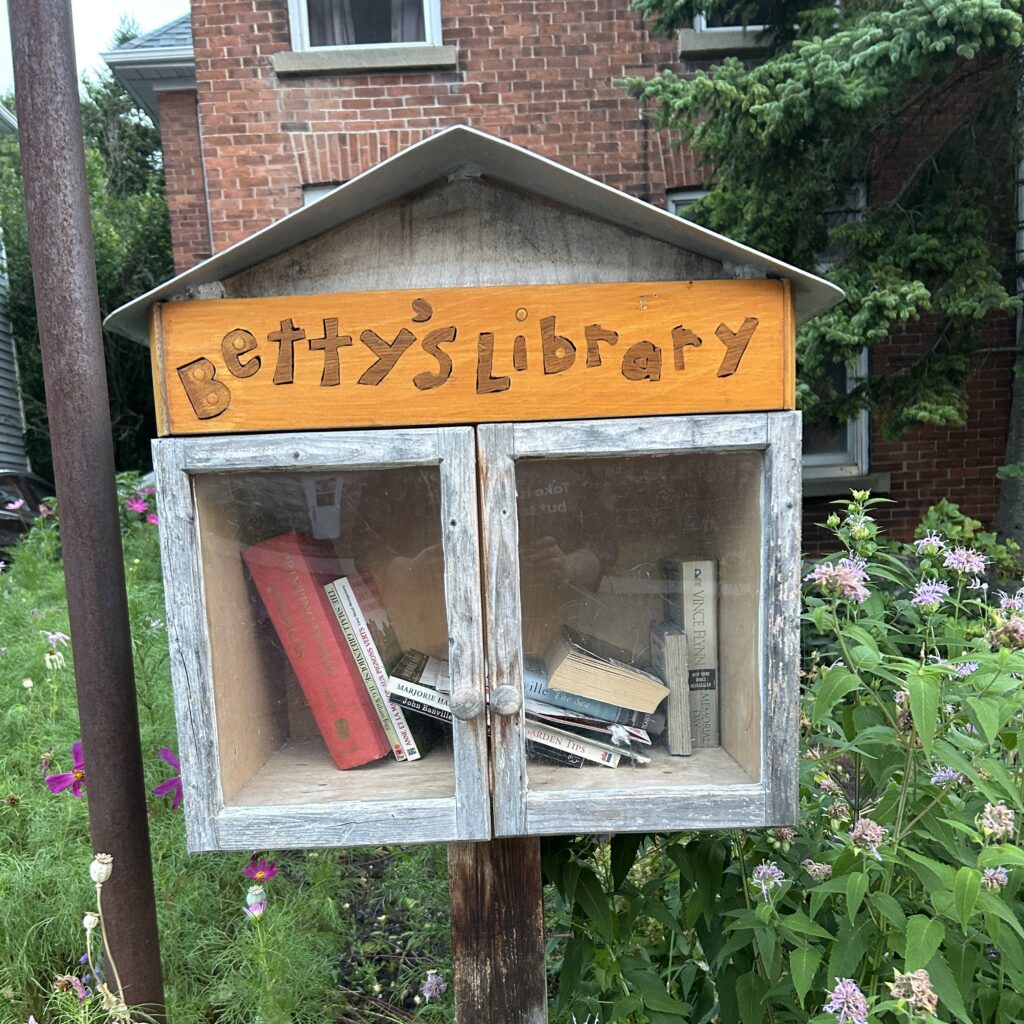

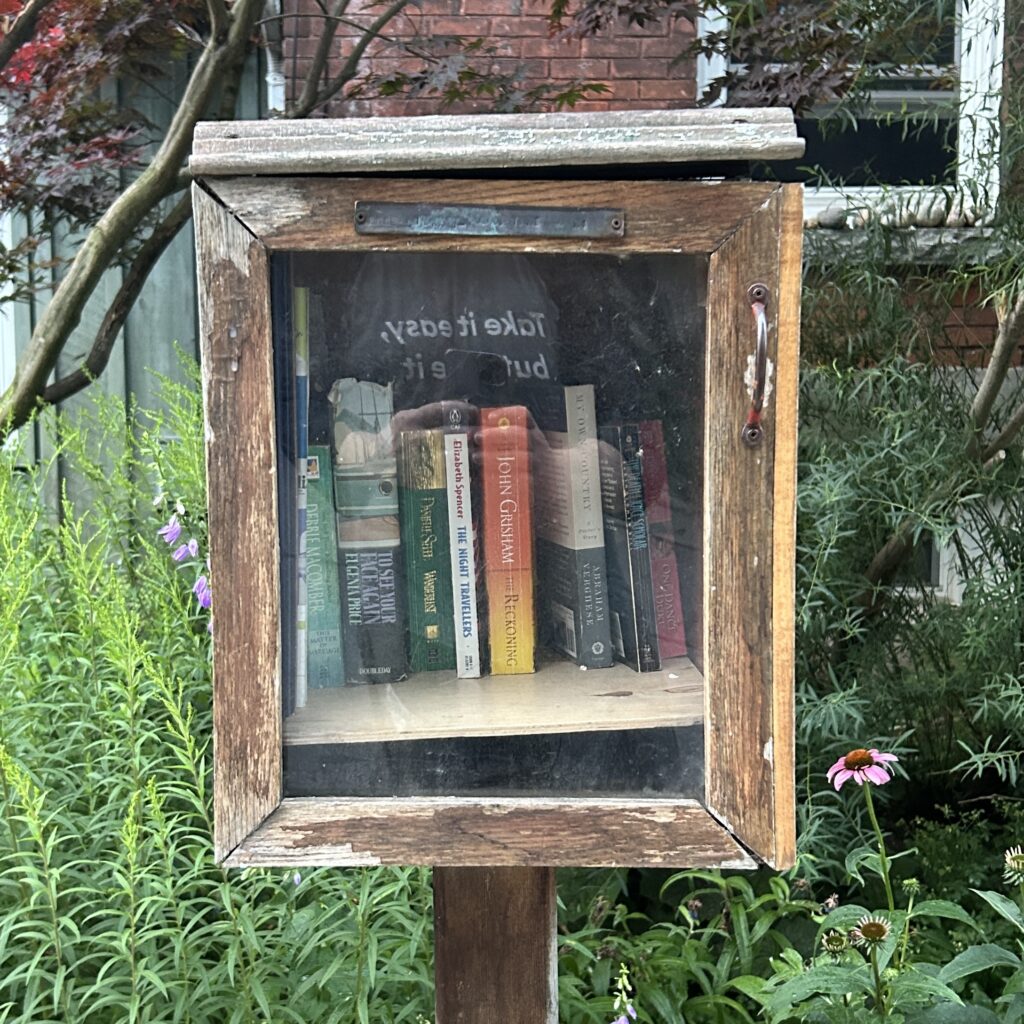

Little libraries and resource boxes of the neighbourhood. They’re, uh, more understocked than I feel they usually are. I didn’t set out to do Sad Photo Series #37. Maybe there’s a seasonality to this. Maybe our capitalist billionaire-fever-dream dystopia is manifesting in new and horrible ways. I dunno.

My new friend, Rick Cigarettes:

Faded Spongebob:

This Telephone Pole Will Change Your Life… Twice

Dumpster Claw

Big Crane on Campus

Best Shawarma In Town

Stauffer Library’s Architecture Makes No Goddamn Sense And Looks Kind Of Like A Hat For Those Game of Thrones Frozen Zombie Things

My Friend Bébé Danger, On Our Garage Roof (1-2)