Sponsorship has been on my mind lately.

As stated, I don’t think it should be a marketing exercise. There’s a significant gap between sponsorship and patronage, and over time, forcing sponsorship through a marketing lens serves both sides of the equation poorly. Marketers are forced to make decisions that shouldn’t have to reside with them. More problematic: sponsors may over time warp their mission and services to attract marketing-driven sponsors.

At its heart, sponsorship is ultimately not a great spend, from a bloodless, calculated marketing perspective. There are times that it works well:

- Huge buys that integrate your organization in an indelible way, turning what you’re sponsoring into a marketing platform for your brand;

- Mega-budgeted presence strategies, where you can afford ubiquity by buying placement in the plurality of places your audience might look.

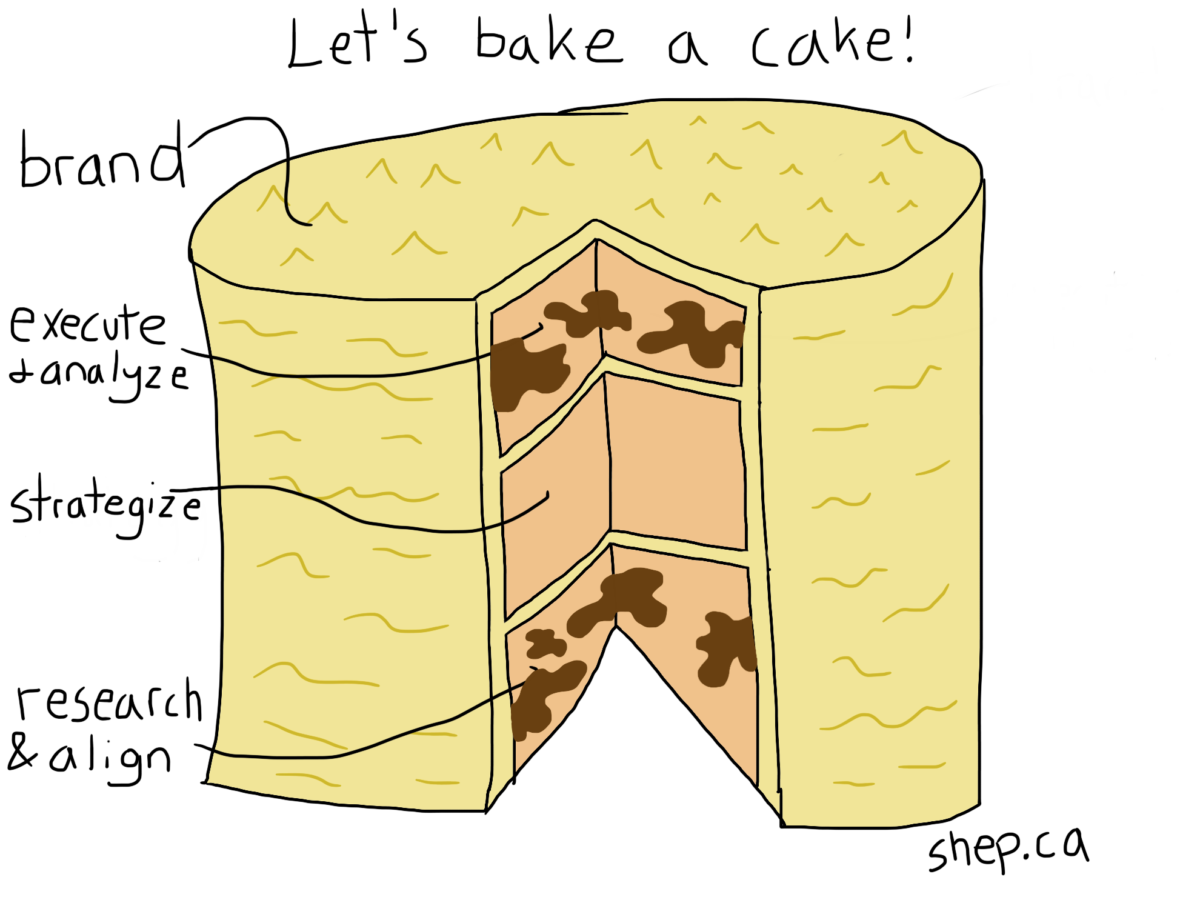

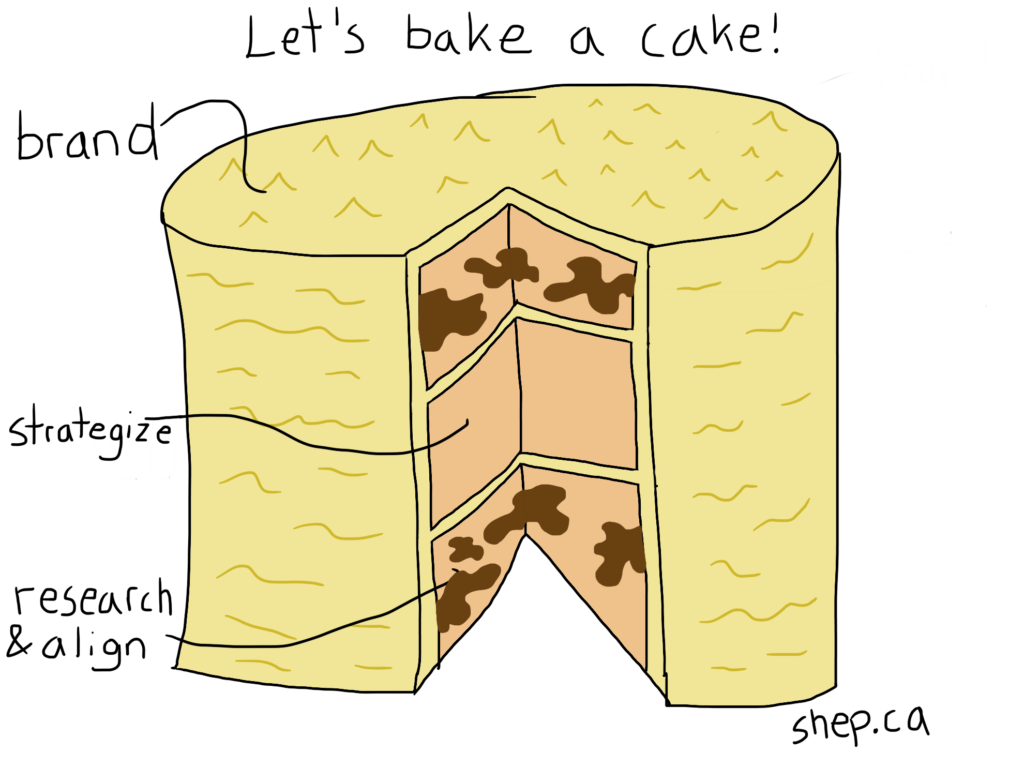

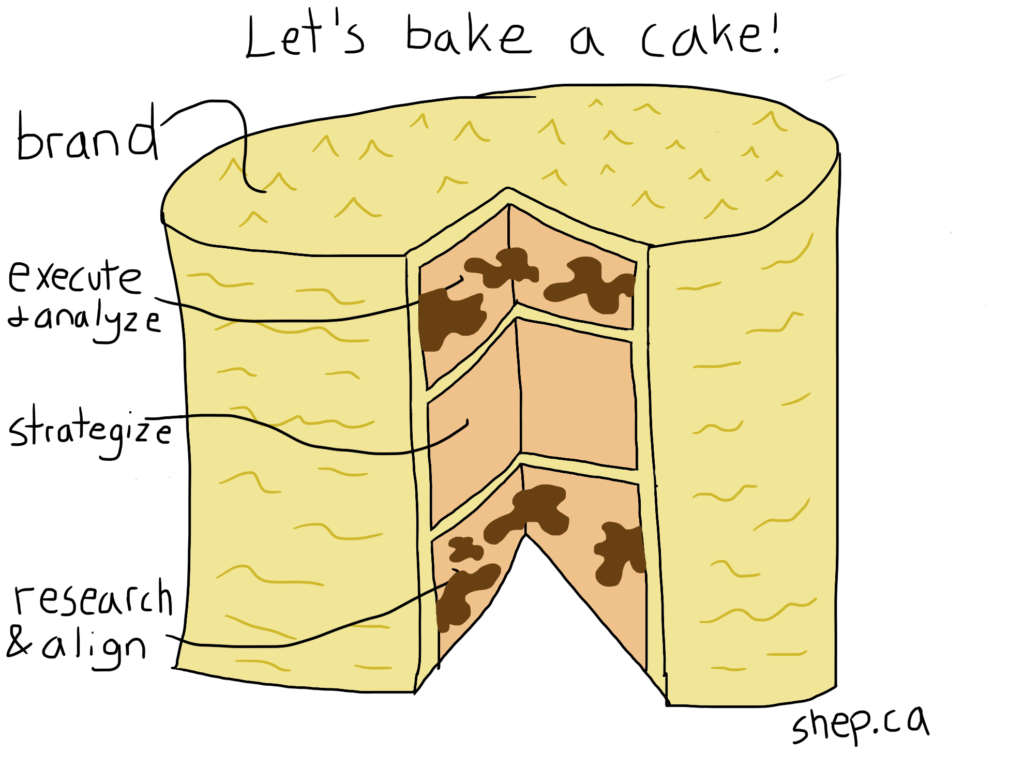

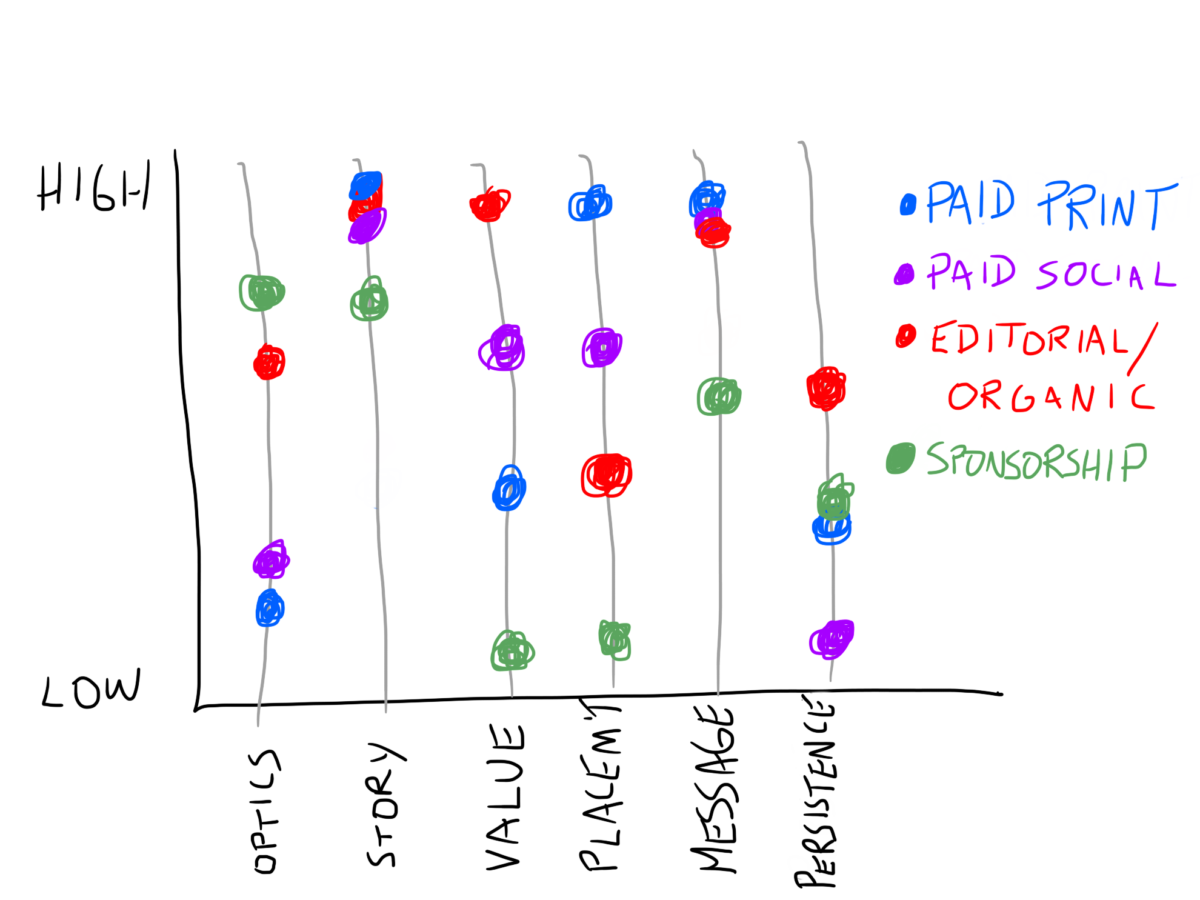

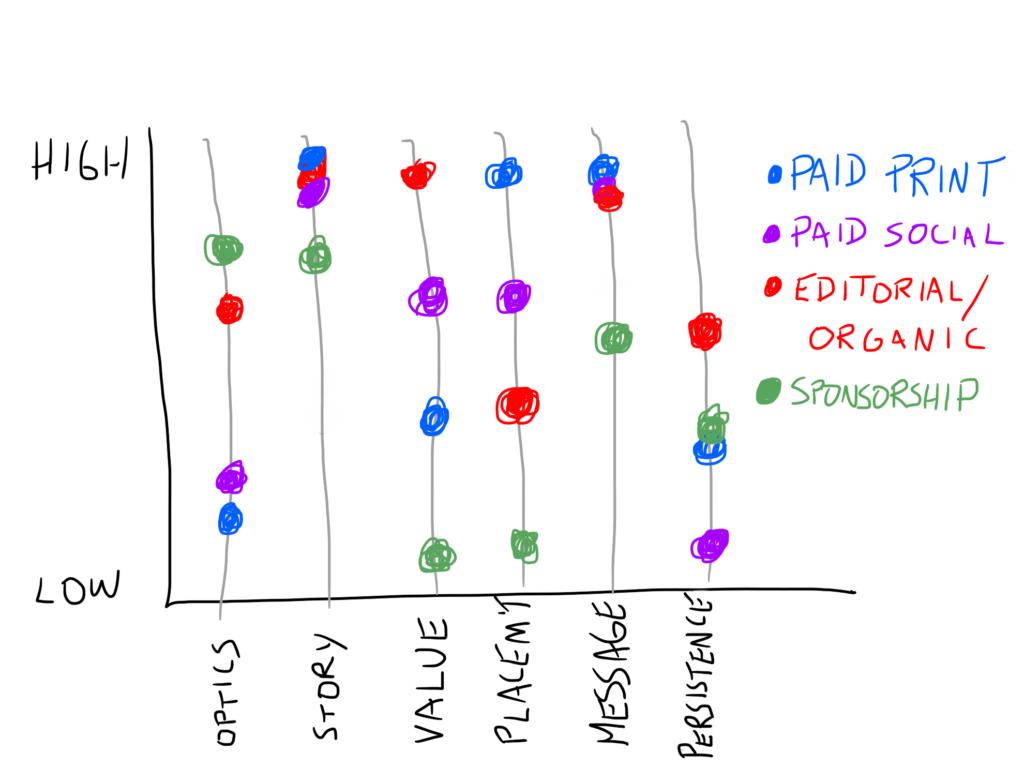

It slots into the top tiers of our Marketing Layer Cake — strategy through tactics, with measurement on the back end.

Discussing this with colleagues, I find there are two views on sponsorship. One is well-trod, the other not thought about as often.

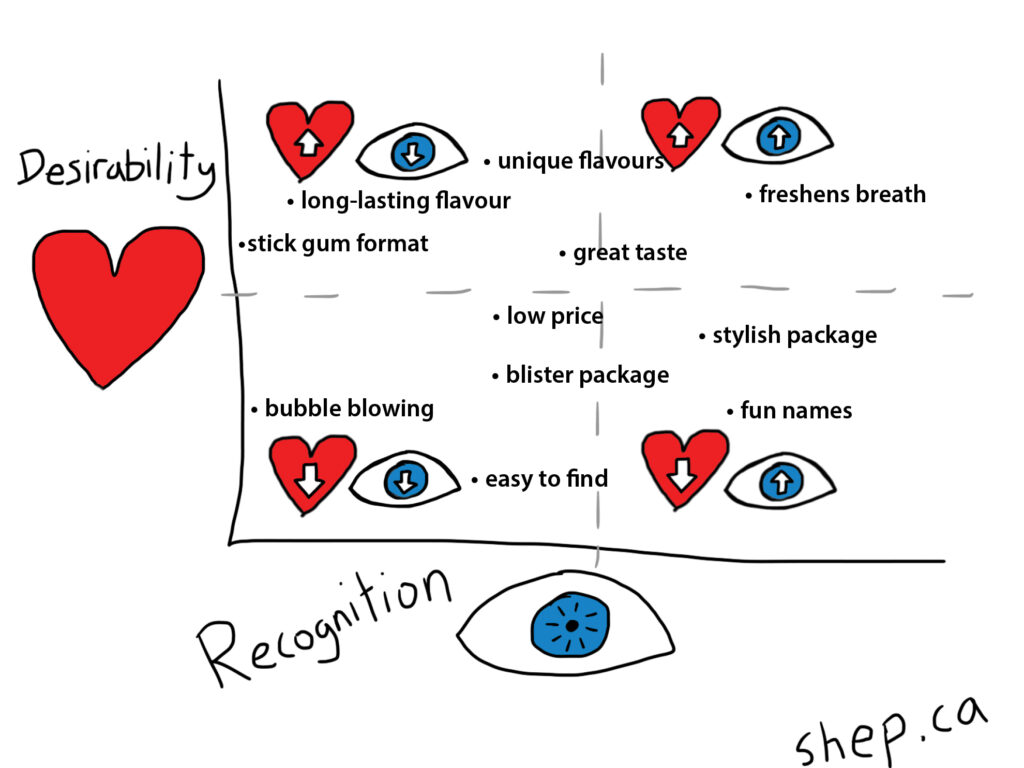

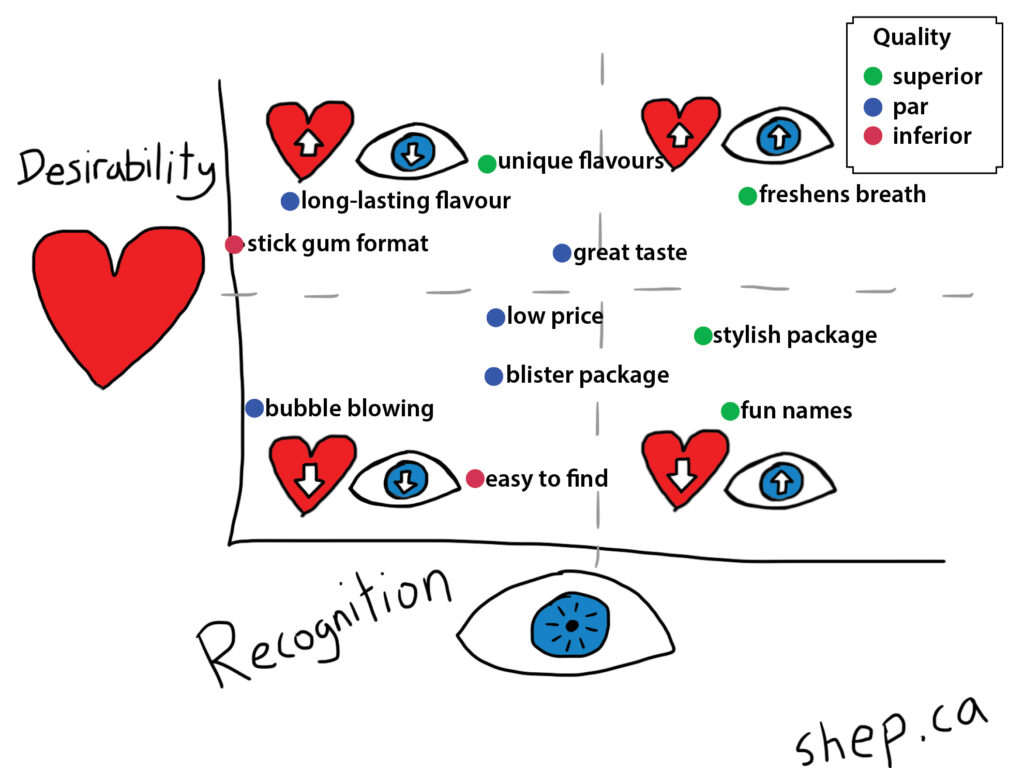

The first is the positive benefit. What does being there do for you? This is the mental calculus behind the two winning strategies above: the big splash, and constant presence.

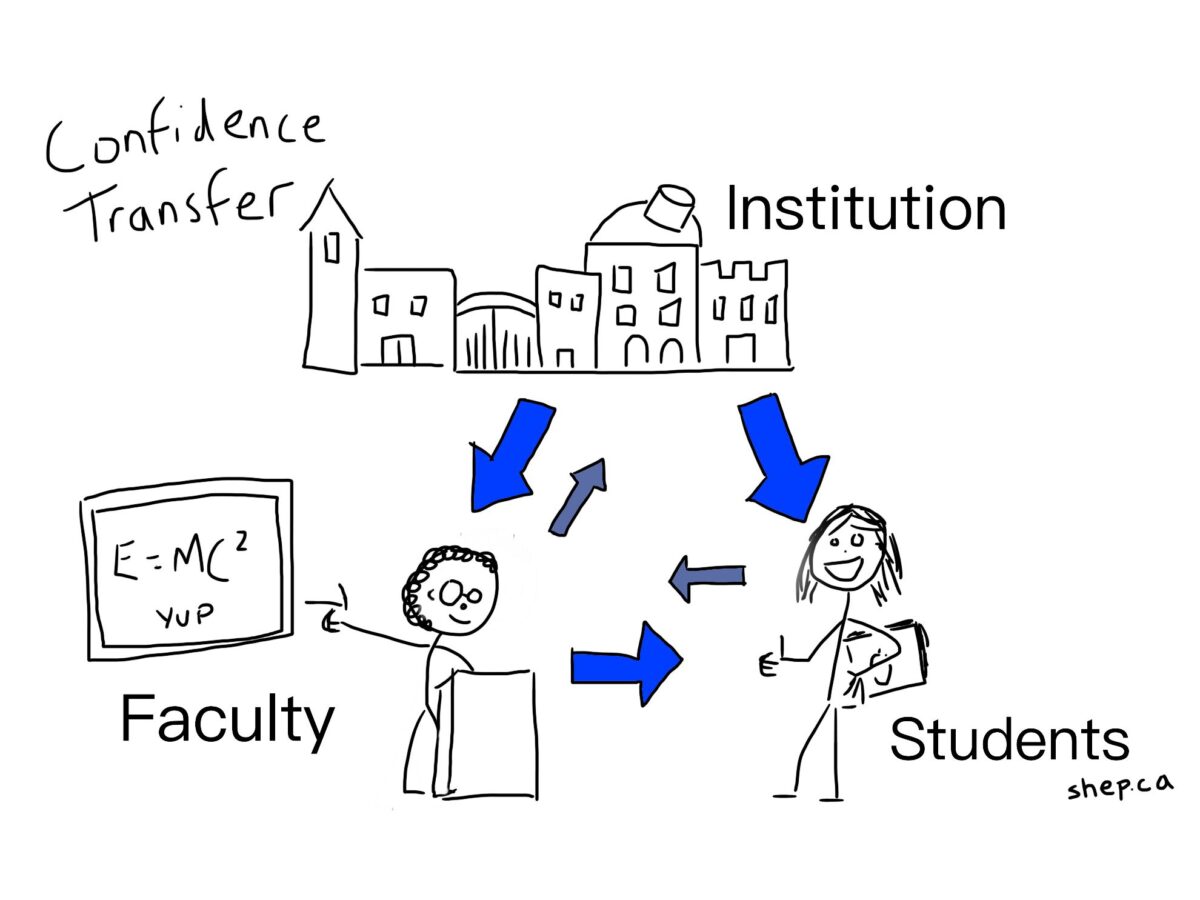

Headlining a conference — the platinum sponsor, logo at the top of the website and letterhead, maybe even naming privileges for the entire shebang — that’s the pinnacle of positive presence. The big splash puts you in front of an audience, in a way that not only gets you eyeballs but also confers credibility as experts (professional conferences, technical symposia, etc.) or solid citizens (charitable endeavours, benefits).

Similarly, constant placement at a bronze-tier kind of level might give you a persistence that is noted — unconsciously — among your key audiences. Maybe. I’m not sure I believe it. It’s the kind of thing I could see myself making a case for, if given a considerable budget and a very specific mandate to grow a reputation with a particular audience. A consistent drumbeat of low-level awareness over time.

Less thought about, in my experience, is the FOMO cost.

Fear of missing out come up a lot when we’re talking about social media adherence, event marketing, and CPG trends — but it’s also a recurring factor in internal conversations. “What if we’re not there? What will people think?” This is the tug for cause-driven sponsorships more than professional ones — if all your competitors are in the mix supporting Cause X, what will you be signalling by not being present?

Having spent some time kicking it around, I keep landing on the “fear” part of “fear of missing out,” and — like most fears — when confronted, I find it’s not as scary as I first assumed.

The mental exercise I’ve been going through is a personal one. I’ve been trying my best to recall various charitable efforts I’ve been a part of. Conferences I’ve attended (and spoken at), conferences I’ve sponsored, and conferences I’ve helped organize.

When I run that inventory, I find I can speak to limited positive presence — usually because I’ve had an impression that affected me above and beyond the sponsorship. A mind-changing keynote can have me remembering a top-tier sponsor. But I’m remembering the keynote in this case — not the logo on the roll-up banner.

This — again — speaks to the “big splash” strategy. Pick one or two things a year and lean in. But this isn’t a financial transaction: it’s a multi-resource commitment, a productive partnership with the organization where you’re committing creativity, thought, human capacity and a lot of time into making their cause your cause and effectively co-opting what you’re sponsoring to serve both purposes equally.

I can’t say, in retrospect, I have any idea of who wasn’t present. This isn’t professional. This is also personal — I am and have been involved with charitable and non-profit organizations. I’ve been on boards of directors, I’ve put together funding drives and events, I’ve organized cross-Canadian conferences, promoted others, and attended others still.

Gun to my head, I couldn’t tell you whether or not Organization X was in the logo soup at the bottom of a roll-up banner in the lobby, or on the back cover of the official program.

I haven’t an inkling.

My absolute best would be “it seems like the sort of thing they might do,” but that speaks to their work in reputation and brand management, not whether or not they ponied up several grand to appear somewhere in the mix. Even for conferences and charitable events I’ve helped organize — I can fuzzily recall top-tier sponsors, but I’m recalling negotiations and the labour of moving logo files around and negotiating placements and various rounds of distro and proofreading.

And this is a challenge I’d extend to you as well — think back to not the last conference you attended, but maybe two or three back. What did you do in 2018? Pull up an event or a cause from 2-3 years ago.

When you think of an organization that might have sponsored that event — not one you presently recall — can you say whether or not they were a bronze-tier sponsor? That they had their logo dutifully slotted into the wash of logos on the bottom quarter of the “Partners” tab of the WordPress microsite that was spun up for the event?

Maybe you can. I move in circles where people are crazy smart and have terrifying superpowers, including incredible recall. I’d venture, however, that you can’t.

And once you remove that FOMO fear — the notion that your not being present will have a meaningful, lasting, negative impact on the brand — the sponsorship drive suddenly abates. It abates tremendously.

The other question — at that bronze-tier, logo-soup level — is what else that money could have done for you. It’s not an expense, it’s also an opportunity cost: hours of time signing up, reviewing the benefits, opting in, signing contracts, submitting invoices, transferring graphics, confirming placement, and so on. One of the reasons I chose higher ed over a fun, creative, highly challenging career in for-profit marketing is that I feel good about higher ed. Educating people and doing research is good. So I don’t have a ton of moral qualms about saying that spending money to ultimately advance educating people and doing research, rather than diverting it into other causes, is a net harm.

Sponsorship is, again, important. But if your motivation is to be seen, the winning plays are to approach it from a top-tier, partnership level — which, with higher ed budgets and staffing, means one or possibly two big pushes a year, factoring in not only financial but capacity impact to make the most of the investment.

If your motivation is the fear of not being seen, I’d encourage you to examine that. Ask yourself when in your life you’ve noticed an absence in a program schedule and it’s had a meaningful and lasting effect on your view of an organization. My gut says the chain of consequence leading from a bronze-tier absence to an actual, broad, negative income is a very long chain indeed.

Both of these things: the desire to be seen, the fear of not being seen… these are marketing concerns. They are mercantile equations. They should be, in my ideal world, secondary to the ethical considerations of sponsorship: what do we believe, who is doing good work to support what we believe, and do we have the resources to support them.

Those ethical decisions are based on belief and values, which are positive forces. Ultimately, this is one of the compelling forces that push me away from affiliating sponsorship and marketing: more often than not, the decision is based on fear, and fear is not a compelling place to make decisions from.

January 17, 2021

Soundtrack:

- Lice (Aesop Rock / Homeboy Sandman), “Ask Anyone” (Single)

- Various Artists, “Nigeria 70: No Wahala: Highlife, Afro-Funk & Juju 1973-1987”

- Dry Cleaning, “Boundary Road Snacks & Drinks”

- Snapped Ankles, “Stunning Luxury”