Something terrible has happened.

In a 24/7 global news cycle, we are all capable — if not always actively engaged — with knowing what is wrong in the world. This means a lot in higher education, which combines international presences with institutional commitments to both recognizing diversity and treating students with empathy and support.

When members of our community are suffering, they look to their institutions for support and understanding, particularly in a public context. A statement in support of their plight means a lot: it shows that the institution sees them, that it cares, and that it is on their side. “We stand with ________ during the __________” messages can mean a lot to the people affected. Doubly so in a lot of ways in higher ed, where a school can be an intrinsic part of one’s identity, above and beyond just a place you show up and take classes. Community, support and spirit are a core part of the value offering of colleges and universities, and the corollary of that is that the demand for emotional buttressing may be greater than one might expect from, say, a favourite fast food restaurant, day job or leisure activity.

Knowing that: why in the world would you not provide your commmunity with leadership, comfort, and goodwill in a time of need?

And I want to be clear here that I’m talking about things that are unambiguous. Tsunami-level disasters. Decrying tyrannical governments or full-on Nazis. This isn’t “take a stand on a highly contentious issue” territory where the risk is that 50% of people will disagree with you: this is “vaccines are good, the Earth is round, ethnic cleansing is bad” issues where sane humans are entirely on board and you can afford to discount the weirdos.

But even in those cases where you’re making a public comment on a fully realized issue that 99% of humanity will back, there are reasons not to do it.

The first is that any comment on that isn’t completely in the ambit of your core mission represents a deliberate choice to make a purposeful statement. It therefore implies choices to not comment on other issues. Speaking out on Issue A is a positive act of support for Issue A, but can be read by people affected by Issue B — for which no statement has been made — as disinterest in what affects them.

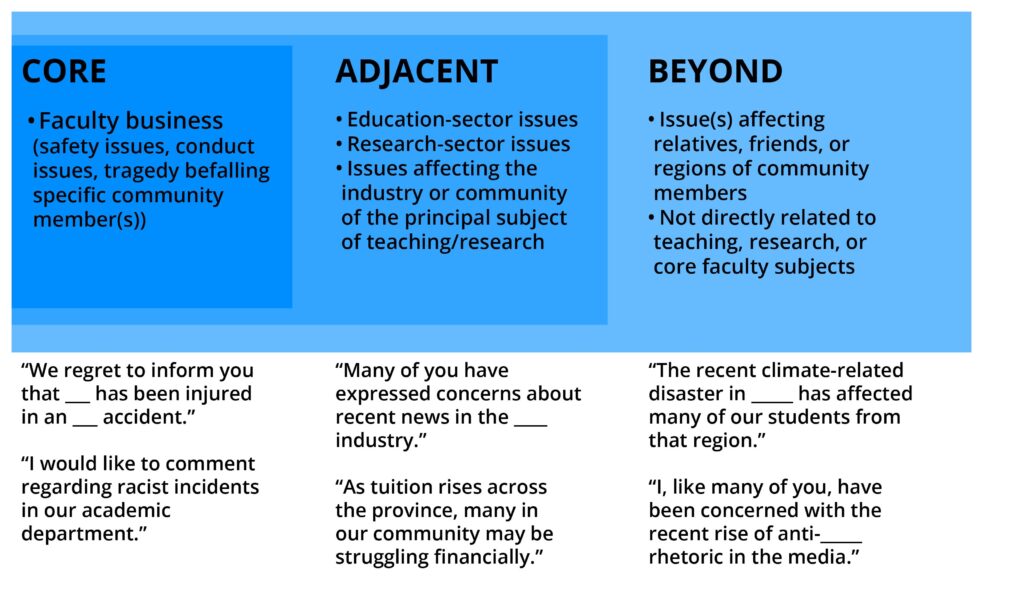

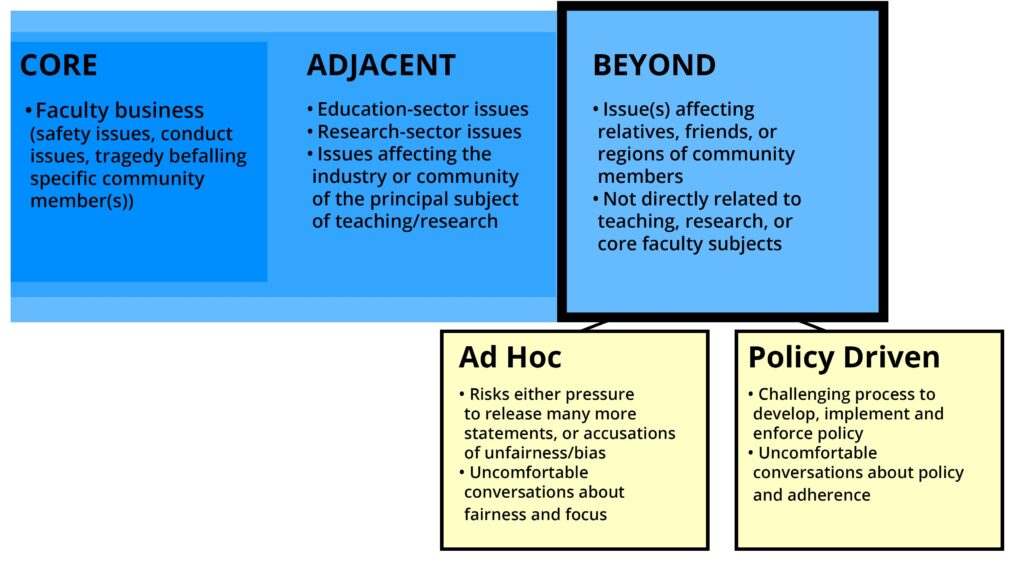

I’m defining “core mission” here as (in a higher ed context) things that in the first order directly affect the school and its community; in the second order, things that affect its educational or research mandate, or have a profound impact on the industry/sector that the primary subject of teaching/research focuses on.

Once you’ve commented on Issue A, subsequent calls for more statements are harder to resist, because there’s now a legitimate area for complaint: if you support this part of the community, why don’t you equally support this other part?

Once you’ve broken the “speak on subjects outside of the core mission” seal, there are three paths:

- Rare statements based on what the administration feels is important, but without a formal policy or guidelines on when a statement should be issued.

- More statements — either on demand whenever a concern is raised or proactively when something that might affect the community is noticed.

- Development of a policy or guidelines that clearly identify what circumstances should generate a statement of support, with statements only issued when the policy supports it.

The first is the default; it’s the status quo, and frankly, it’s… probably fine? I haven’t noticed our institutions crumbling to dust around us. Issues with this approach manifest themselves chiefly in planning — it’s hard to know when the call will be made, and what kind of a statement and what kind of distribution will be desirable. The other is the spectre of bias and resulting reputational risk: why did you speak up to support group A and not group B? Why do you care about issue Y and not issue Z?

These play out internally, for the most part. There’s an ever-present risk of getting a black eye on social media over supporting A but not B. Since there’s already commenting on A, and no policy in place, it’s a legitimate question, which makes public criticism more pointed. That leads to a temptation to just speak on Issue B as well. And over time, this can lead to…

The second path — lots of statements, without a clear policy on why and when they’re being issued. This is the least good option; the more an insitution diverts itself to talking about things fundamentally unrelated to its core mission, the more it is diluting its own message and purpose. Which, in at least the case of higher education, are things that are also worthy of support: research, education. There’s also a question of what message this sends internally — if the institution we’re looking to for stability and support is constantly reminding us of crises and tragedy, even through support messages, what does that do to people who want safety and steadiness in the world? This is almost an inevitable path to…

The third path — policy. Which provides clarity, but ultimately opens the institution up to the same criticisms as the first path, with the additional disadvantage that somebody has actually sat down and tried to write out a formula that quantifies human suffering. Does one measure the “statement-worthiness” of an issue by deaths? By trauma? By the percentage of the community it affects? Who drafts it? Who approves it? How and where is it published to refer to, and who handles complaints about the policy? On its face, “write policy” seems like a straightforward path, but it’s a fraught one.

And that brings us to moral courage.

Two flavours of it.

The first is sticking to the “official statements in our area of expertise” guns. No matter what happens in the world, in scope or scale, you just adhere to the non-policy of speaking only on issues that affect your core mission.

The second is feeling moved to comment on something outside your remit, knowing this may lead to accusations of unfairness, difficult-to-navigate conversations about statements on other issues, and public pressure from people pro- and anti- whatever you are commenting on… and doing it anyway.

Both represent a kind of fortitude; both are about a willingness to have hard conversations about difficult topics, and possibly suffer some public lambasting regardless on where you fall on the issues.

The first gives you an easy response (if sometimes tough conversations) to requests for statements. The second leads to challenging responses to the same questions — but is also for something.

My own thinking on this has been, frankly, muddy. I feel like I’ve been slowly sloughing through the practical, moral, and logistical issues around public statements for years, and have been very slow in coming to a conclusion that people with a stronger moral compass than I have probably would get to a lot quicker:

Some things are worth the risk.

The institution-only statement path is one that is simple and easy to follow. It’s driven by clarity, but also, it could be argued, by fear: we don’t want to deal with the risk of these other conversations about fairness; we are anxious about being driven down paths where we have to publicly navigate questions about what and who we support, and why.

As a naturally risk-averse person, I fully identify with the anxiety.

Which is why I’ve come to appreciate the statement-makers more of late: I don’t think they’re ignorant of the risks above (although they may not have ever articulated them like this). I think they are just okay with them.

I’m very slowly reversing gears on a long tradition of counsel to just stick to the institutional mission and not colour outside the lines. I think — if the risks are known, and accepted — it’s more courageous to take the risky statement route than not.

This is possibly a very long walk to cover a very short distance, but hopefully it lands with somebody who’s going through the same slow slog I’ve been undergoing for the last few years.