Hey! It probably goes without saying that I am not a lawyer and nothing in this blog is legal advice. But I’m saying it anyway!

The first thing we read in my privacy law class was “The Right to Privacy,” Samuel D. Warren and Louis D. Brandeis.1Samuel D. Warren & Louis D. Brandeis, The Right to Privacy, 4 Harv. L. Rev. 193 (1890). First published in the Harvard Law Review in 1890, it’s generally accepted as the initial stake in the ground for privacy rights. While there’s a lot that follows in the intervening 130-plus years, it firmly establishes the right to be “let alone,” a phrase made famous again in 1955 by Greta Garbo (and repeated in 50% of law school papers on privacy).*

Here’s “The Right to Privacy”, if you want to read (or re-read) it.

When you read it, the inciting behaviour is clear: gossip, specifically “society columns” in the newspapers of the day. Look at how tightly this article is bound to photography. Taking the introduction of “to be let alone” in the article, photography kicks off the very next sentence (emphasis mine):

Recent inventions and business methods call attention to the next step which must be taken for the protection of the person, and for securing to the individual what Judge Cooley calls the right “to be let alone.” Instantaneous photographs and newspaper enterprise have invaded the sacred precincts of private and domestic life…

And we’re off to the races! Thanks to Warren and Brandeis, hereafter WAB, because it’s short and also because it’s a lot like WAP and that’s fun for me.

I’m making a big deal out of this because as a higher ed marketing & communications professional, photos are a very big deal. And this is (broadly speaking, there are antecedents2I highly recommend Solov’s “A Brief History of Information Privacy Law” — Solove is going to come up a lot in this series, I think, including next week when we look at Prosser. Daniel J. Solove, A Brief History of Information Privacy Law in PROSKAUER ON PRIVACY, PLI (2006).) — WAB even mention that it had “already found expression in the law of France”3WAB’s footnote mentions the Loi Relative a la Presse of 1868, which is very elusive to find, or find writings on; if you are or know a French historical legal scholar, maybe you’d have better luck than I tracking this down — the kick-off for the very notion of privacy rights, which are the legal construct that leads to photo/video consent as both a practical and philosophical necessity. We can’t talk about consent without talking about privacy… and we can’t talk about privacy without talking about WAB.

So here we are, discovering that photography is baked right into the history of privacy-as-a-right.

It’s no secret that “The Right to Privacy,” while far-reaching in scope, was inspired by Warren’s profound irritation with what we’d call paparazzi today, who crashed and wrote about a society wedding.4Prosser, W. (1960). Privacy. California Law Review, 48(3), 383-423. doi:10.2307/3478805 The word “paparazzi” was still 70 years from being coined — eponymous for a character in Fellini’s La Dolce Vita — but clearly photographer-as-pest was enough of a common social ill, even in 1890, to resonate.

It’s fun, if pointless, to wonder whether the idea of a right to privacy would have arisen, and in what form, if photography hadn’t gone the way it had — or if people had left the family wedding alone, or if WAB had thicker skins. Things rolled out the way they did. It’s interesting, though, to look at subsequent developments in privacy law and note how correlated they are with identity and revelation: presentation, photography and video as the drivers of a lot of our notional understanding of privacy.

So what is privacy, as they frame it?

Privacy is a negative right

Right out of the gate: privacy isn’t a right to do something, it’s a right to not have things done to you. WAB: “It is like the right not to be assaulted or beaten, the right not to be imprisoned, the right not to be maliciously prosecuted, the right not to be defamed.”

It’s not copyright, libel or slander

WAB go to some pains to ensure that the right to privacy is distinct from existing rights. Copyright is identified as a branch of property law. They do, however, use the idea of privacy law to colour in areas around copyright law. Where copyright law would protect a literary or artistic work, it still doesn’t prohibit the sharing of details or facts about people’s lives. WAB sketch out scenarios of letters between husband and wife, or a catalogue of gems that would be ruinous to a jeweler if released. “If the fiction of property in a narrow sense must be preserved, it is still true that the end accomplished by the gossip-monger is attained by the use of that which is another’s, the facts relating to his private life, which he has seen fit to keep private.”

Libel and slander are deemed to protect “the material, not the spiritual” (197) — protecting from damage and injury to reputation. The proposed right to privacy, unlike libel / slander / defamation, does not offer the truth as a defense, however.

It’s constrained by practical matters

The authors also set out some fences that mesh with fairly common-sense propositions: once something is published (by consent), it’s no longer private; matters “of public interest” aren’t private (so publishing the backroom dealings of a politician are fair game, for instance). Constrained “privileged” publication, such as in court, government committees, or other public bodies, don’t violate the right to privacy. Oral violations would likely be without redress, because the damage would be very limited.

No malice required

They also take pains to point out that an absence of malice is no defense — that personal ill-will is not a requirement of a violation of the right. This is a through line with tort law — ill intent generally isn’t necessary to be held responsible for intentional acts.

Setting the table for 130+ years of privacy evolution

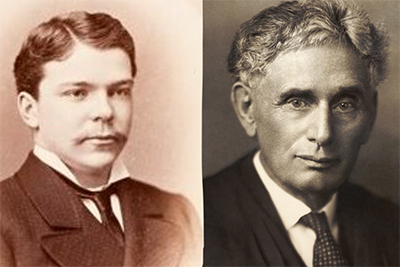

Warren is the guy who looks like a turtle soup magnate on the left, Brandeis on the right looking like he’d be right at home presiding over an orphanage in a Dickens novel. It’s fun to imagine them popping their monocles over gossip columns — but this was a big idea; important work, that would leave gossip in the dust over the next century-plus and become a foundational concern for society today.

They also weren’t shy about tossing a little hyperbole in the mix:

If casual and unimportant statements in a letter, if handiwork, however inartistic and valueless, if possessions of all sorts are protected not only against reproduction, but also against description and enumeration, how much more should the acts and sayings of a man in his social and domestic relations be guarded from ruthless publicity. If you may not reproduce a woman’s face photographically without her consent, how much less should be tolerated the reproduction of her face, her form, and her actions, by graphic descriptions colored to suit a gross and depraved imagination.

Although privacy law now covers everything from financial data storage to how censuses work, my interests, as somebody who works in higher ed marketing and communications, are still in roughly the same ballpark as WAB. As somebody who is responsible for creating, and publishing, a lot of pictures and videos in a lot of different ways, how can I do that in a way that upholds the spirit of a right to privacy, while still operating effectively and efficiently?

It’s a compelling question, for me, and I’m going to keep diving into it for a while.

Sidebar: so who was Judge Cooley?

Because I get curious about things, I couldn’t help wondering who “Judge Cooley” is. He’s actually the cited author of the four-word “to be let alone” phrase that anchors this whole thing. It’s like if I wrote a long essay saying that somebody should, as the Fonz says, “sit on it”, and I become known as the genius who first established that somebody should sit on it. I should hope that future scholars would one day work to uncover this mysterious “Fonz” from who these words of wisdom came.**

Cooley (Thomas M.) seats the right “to be let alone” in a general treatise on torts from 1879; in Chapter II of A Treatise on the Law of Torts or the Wrongs Which Arise Independent of Contract, “General Classification of Legal Rights,” he lists “Security in person” as one of the rights that a government is expected to recognize.

In that vein, and following “Right to Life,’“ “Personal Immunity” is the second right he lists; and here’s where we get to it (emphasis mine):

“The right to one’s person may be said to be a right of complete immunity: to be let alone. The corresponding duty is, not to inflict an injury, and not, within such proximity as might render it successful, to attempt the infliction of an injury. In this particular the duty goes beyond what is required in most cases; for usually an unexecuted purpose or an unsuccessful attempt is not noticed. But the attempt to commit a battery involves many elements of injury not always present in breaches of duty; it involves usually an insult, a putting in fear, a sudden call upon the energies for prompt and effectual resistance. There is very likely a shock to the nerves, and the peace and quiet of the individual is disturbed for a period of greater or less duration. There is consequently abundant reason in support of the rule of law which makes the assault a legal wrong, even though no battery takes place. Indeed in this case the law goes still further and makes the attempted blow a criminal offense also…”5Cooley, Thomas M. A Treatise on the Law of Torts or the Wrongs Which Arise Independent of Contract. Chicago: Callaghan and Company, 1879; pages 23, 29.

This is actually pretty interesting. Cooley is engaging in a pretty straightforward description of assault and battery. (Fun fact: in Canadian law, there is no “battery” in the Criminal Code — “assault causing bodily harm” carries the weight there. But “assault” and “battery” are still torts; as you can infer from the criminal distinction, “battery” is the physical harm portion, and “assault” is the menace. If I run up to you with an axe, screaming, and swing the axe but stop it an inch shy of your face — that’s still assault, even if no physical harm is done. It’s actually a pretty broad category of things (including throwing a cat!).6He doesn’t cite the case here, but if a lawyer is going to say that throwing a cat is assault, I’m not going to miss this opportunity to write about it. John Erikson, “What are the different types of assault charges in Canada?” at https://ericksonlaw.ca/different-types-assault-charges-canada/

So, in A Treatise on Torts, Judge Cooley is describing “a right of complete immunity: to be let alone” in the context of the legal wrong of assault.

WAB have picked up Cooley’s turn of phrase originally used to describe assault — inflicting credible menace on somebody — and turned it to the purposes of privacy.

This is not an accident — they even describe the evolution of assault from battery on the previous page. Judge Cooley and A Treatise on Torts would have been a seminal book by 1890. So it’s fair to say that WAB knew exactly what they were doing with the lift, knowing that their audience would also likely be familiar with Cooley: invading my privacy is a form of assault.

Also worthy of note — significant mainly in one of the exceptions — consent is also part of the DNA of this first stake in the ground. It comes up a few times in the document, particularly as one of the limitations of the proposed right. Interestingly, the paper’s longest footnote concerns consent via copyright, contract and photo reproductions, substantially quoting North J in Pollard v Photographic Co. on contracted use of negatives.

And — also worthy of note — is the fact that on their surface, WAB, through one lens, failed. If they were writing in the hope of stopping the dissemination of society gossip, a quick trip to a supermarket checkout counter — or any news website — will show that society gossip, evolved into celebrity gossip, is far from gone. The seeds of contemporary gossip-mongering are captured in their very own exception to the idea of a right to privacy: “The right to privacy does not prohibit any publication of matter which is of public or general interest.” This is a massive and swampy grey area, that we’ll get into with century-later court cases involving supermodels and princesses. Stay tuned! But if their goal was to shut down the gossip industry and ensure that the private lives of the rich and famous could not be touched by the grubby, ink-stained fingers of those filthy journos… this was far from an unqualified success.

So let’s keep the following in mind as we meander through the evolution of privacy as a notional right, with a particular interest in privacy in public…

- Photography is comingled with the genesis of a legal right to privacy

- As is consent (but as a factor that waives privacy rights)

- The authors lifted language used to describe assault to define this right to privacy

Next week: Prosser, and the next big hop forward in conceptualizing privacy… for good, and for ill.

*In one of pop culture’s more famous misquotes, she was frequently reported as saying “I want to be alone,” which she clarified in a 1955 interview as having actually said “I want to be let alone.” If you don’t grok the distinction, read on!

**It turns out that the Fonz didn’t actually say “sit on it” very often — it was more commonly said by Joanie and Mrs. Cunningham. Ayyyyyyy!

May 16, 2021

Soundtrack:

Phil Collins, No Jacket Required

Buddy Rich & Max Roach, Rich vs Roach

Sleater-Kinney, All Hands on the Bad One

- 1Samuel D. Warren & Louis D. Brandeis, The Right to Privacy, 4 Harv. L. Rev. 193 (1890).

- 2I highly recommend Solov’s “A Brief History of Information Privacy Law” — Solove is going to come up a lot in this series, I think, including next week when we look at Prosser. Daniel J. Solove, A Brief History of Information Privacy Law in PROSKAUER ON PRIVACY, PLI (2006).

- 3WAB’s footnote mentions the Loi Relative a la Presse of 1868, which is very elusive to find, or find writings on; if you are or know a French historical legal scholar, maybe you’d have better luck than I tracking this down

- 4Prosser, W. (1960). Privacy. California Law Review, 48(3), 383-423. doi:10.2307/3478805

- 5Cooley, Thomas M. A Treatise on the Law of Torts or the Wrongs Which Arise Independent of Contract. Chicago: Callaghan and Company, 1879; pages 23, 29.

- 6He doesn’t cite the case here, but if a lawyer is going to say that throwing a cat is assault, I’m not going to miss this opportunity to write about it. John Erikson, “What are the different types of assault charges in Canada?” at https://ericksonlaw.ca/different-types-assault-charges-canada/