Last week I was talking about how internal communications is hard in higher ed. A college or university is a massively complex and internally competitive system, with students, staff and faculty operating on multiple layers at once, and with concerns and needs that bridge from “professional” — i.e. studies, to personal — i.e. mental/physical wellness, and everything in between.

This is a four-part series on internal comms in higher ed:

Part One is about the hugeness of the issue;

Part Two is here, about the hazards of conflating channels;

Part Three is a flailing attempt to make a case for resourcing this;

Part Four is a sandwich-themed run at a solution.

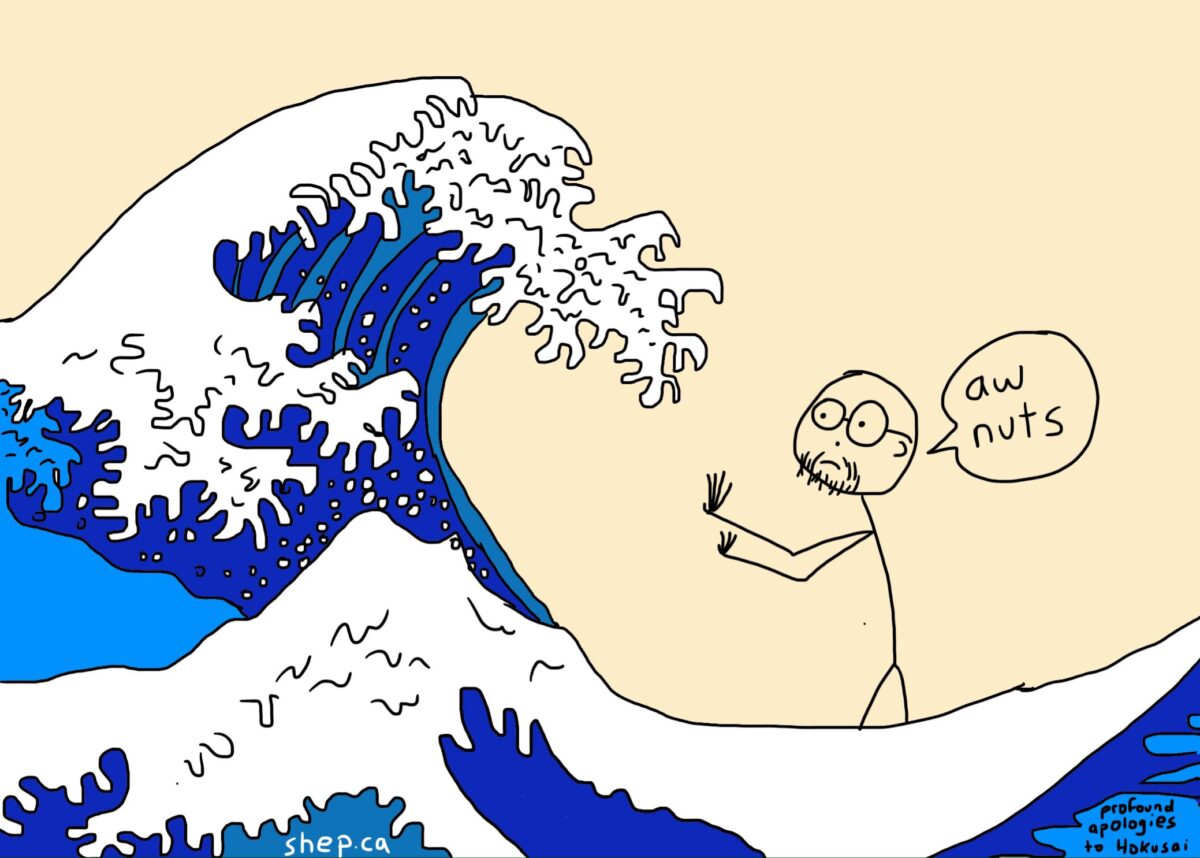

Putting internal messages on external channels is a delicious trap.

It’s not uncommon for me to get something in my inbox and somebody asking me “can we advertise this to students on social media?” And — absent a clear sense of who is following us where — that’s a hard request to say no to, on its face. Some students are following us on social media. I’m certain of that. We can put things on social media. That’s an absolute. So why not put a wonderful thing on social media for our current students? After all…

- We have amazing-stuff-for-students peanut butter.

- We have channels-followed-by-students chocolate.

- Why in the world wouldn’t you combine the two?

Because while it’s an amazing idea for a snack, if you are handling both internal and external messages, it’s not a great approach to either internal communications or outward-facing media.

Appealing as it is, you gotta keep the peanut butter and chocolate apart.

I’m going to lean into ‘“student recruitment” as the lens I look at a lot of this through. It’s a pretty common thread through higher ed, on the minds of most marcomms folks, and frankly a pretty big deal for me.

This all seems a bit overblown at first, especially to somebody that just wants to tell students about something they feel the students should know.

We’re trying to give prospective students a positive impression of campus, the argument goes, so showing them the breadth of our supports and services is good. Why not remind students to update emergency contact information via Instagram? Where’s the harm?

I do it myself — we ran a 14-day self-isolation-supporting contest series through social recently, to encourage good COVID practices and also student use of our faculty’s app. We just promoted our “Discipline Nights”, where first-year engineers choose an education stream. I did this partly because I have don’t have other strong alternatives to reach our students. But it felt wrong. Here’s why.

The internal-on-external argument

There’s a rationale that, on its face, supports internal messaging on outward channels, in the absence of a strong stated purpose for the channel, or even if the purpose includes recruitment.

A student considering our school…

- may see posts directed at internal students about an interesting service or feature;

- will be impressed with the breadth of services and our community spirit;

- this might make a difference when they choose a school.

It makes sense.

It’s also wrong.

The wrongness of it comes down to the need for channel focus, what the purpose of a channel is, and whether or not what you’re doing on that channel supports that exact purpose.

Social media is bananas, and channel focus is critical

Social media delivers posts haphazardly, through an algorithm that evolves constantly. There’s no guarantee that anyone will see anything you post. The algorithm, that shadowy and terrible master, waves its inscrutable hand and a post lives or dies.

That fact brings the need for focus into focus.

If I want to recruit a student using Instagram, and it’s a dice roll about what they’ll see, I need to ask myself whether I:

- want to guarantee what they see will reflect what prospective students look for in our program

- want to roll the dice and accept that they might see something about a candle-making workshop instead

Wait, though — where’s the harm in sharing a candle-making workshop? Doesn’t that just show breadth, foster the idea that this an interesting place where candle-making happens, and reinforce how lovely our school is, overall?

But social media isn’t the place to show breadth. It’s the time to pique interest, spark imagination, and get audiences to where the breadth is, but it’s not the right venue to dig into the layers of what your school offers — even if those offerings are truly great.

University choice is based on high-tier decisions.

Students, at the recruitment phase, don’t know what they don’t know.

And social media, moving at 10,000 posts a minute, delivering things according to an opaque algorithm, isn’t the venue to educate them.

To use an example from my own life: I’m a proud graduate of Ryerson’s Radio and Television Arts program, class of ‘95. It is a tremendous program, and I don’t think anyone knew how poorly its name would age (it’s the “RTA School of Media Arts” now — good call, Ryerson).

When I was a fresh-faced young lad circa 1991, I wanted:

- to learn cool media stuff

- to work with cool equipment

- get a job in TV or radio or something

- at a place with a really great reputation

That was my chocolate. I wanted chocolate.

What I didn’t know, when I chose Ryerson, was that RTA was a lot more than that. I learned an amazing amount about story structure and writing. Mandatory voice training gave me an amazingly versatile skill that’s served me well since. The most valuable classes for me — which I at the time thought were a monumental waste of time — were Jerry Good’s management courses. Jerry, if you are reading this for some reason now, I am sorry.

There were also stellar services — a great gym, amazing faculty delivering electives to students resenting the “breadth requirement”, student wellness staff — all things that I didn’t know about when I chose Ryerson. That was the peanut butter, and I didn’t know how amazing the peanut butter was when I was picking a school.

But I only wanted chocolate when I chose Ryerson. I was a dumb kid who wanted to learn cool media stuff, work with neat gear, etc.

Had social media existed at the time, and the only messaging from Ryerson that crossed my path had been about their English electives or management seminars or their gym equipment, my life might have turned out very differently.

If I wanted chocolate, but I saw peanut butter, zooming past with a million other factors and things to consider, and messages zipping along at a mile a minute, the idea of combining the two wouldn’t have even crossed my mind. Another school — providing chocolate — would have pulled me in.

If you have a fact-based understanding of what your prospective students want from a school, and you know how to reach them, you’re doing yourself (and them) a disservice by muddying the waters with things that not only won’t resonate, but will likely just be forgotten as they scroll past 10,000 things that don’t catch their eyes or imagination.*

There are definitely times and places to hip prospective students to what you offer that might not be on their radar: student information sessions, tours (real or virtual), the second- and third-tier pages of your website.

But social media’s not the place to do that.

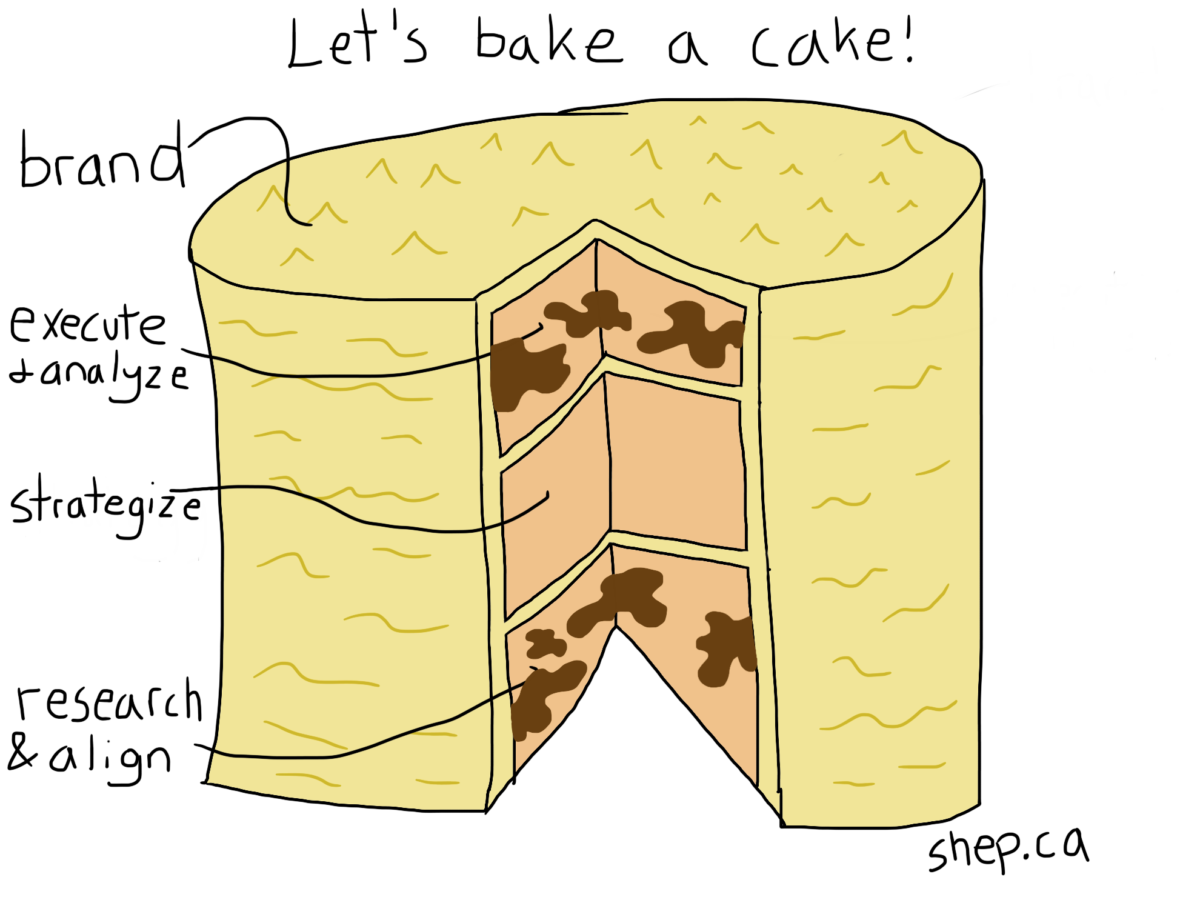

Which brings me back around to one of the primary reasons that a good, planned, robust internal communications system is vital.

I’ll get into more reasons next week, but from a strictly operational perspective, and especially with limited time and resources, it’s crucial to keep those streams apart. Your best chance of success on social media is with a clear, research-backed vision and purpose, and strict adherence to that vision. This isn’t to say it can’t be fun, or interesting, or enlightening, but the job is to drive an interest to learn more — which leads to the breadth — rather than trying to front-load the breadth.

I’ve just spent 1200 words explaining why social media needs to be to the point; the irony’s not lost on me. This hopefully unpacks the internal/external trap well, though.

Next week: why I think internal comms is worth the effort, and how to approach an impossible task with limited resources.

January 31, 2021

Soundtrack:

The Free Design, “Butterflies are Free: The Original Recordings 1967-1972“

Various Artists, “Cuba: Music and Revolution / Culture Clash in Havana“

PJ Harvey, “Let England Shake“

*there’s a lot of complexity to this as well, especially since received wisdom of “what students want” plays into what a traditional plurality of students want; a colonial education system can’t self-correct without self-reflection and efforts toward EDII, which means thinking past received wisdom and what the traditional plurality is looking for. I think this leads to a nuanced conversation about how to reach students with EDII messaging through systems that still deliver high-resonance messages in ways that creatively capture EDII needs — but that’s not really what today is about, and I’d be doing that whole topic a disservice by trying to cram it into a footnote here.